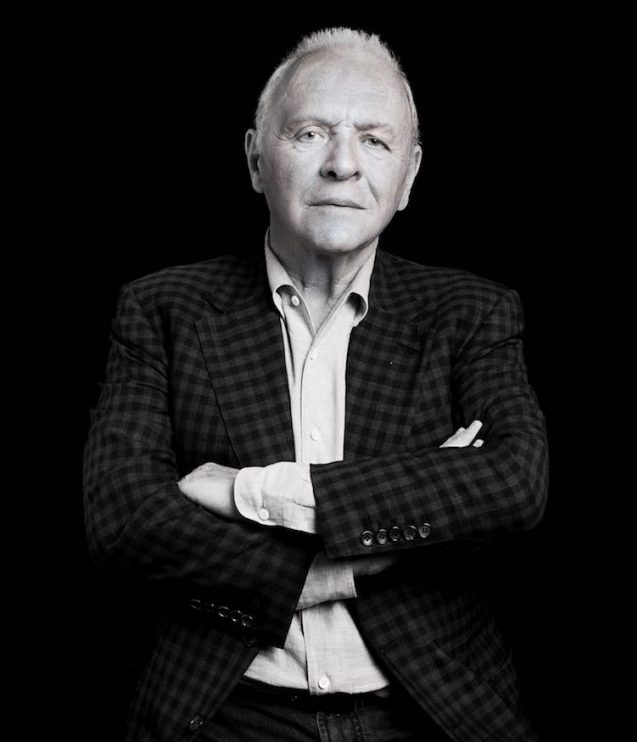

ANTHONY HOPKINS TACKLES DEMENTIA IN HIS LATEST ROLE, AND IT’S GIVEN HIM AN EVEN DEEPER APPRECIATION FOR LIFE.

BY: LAURA SCHREFFLER

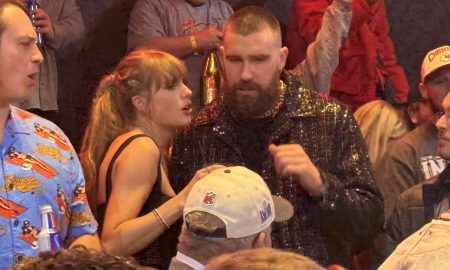

PHOTOGRAPHY: ANDREAS BRANCH

SIR ANTHONY HOPKINS KNOWS WHAT IT’S LIKE TO LITERALLY LOSE HIS MIND. BUT NOT, YOU KNOW, IN A FAVA-beans-and-Chianti, let-me-eat-your-liver kind of way.

The year was 1996. Then 58, Hopkins was shooting The Edge in the wilds of Alberta, Canada, with Alec Baldwin. Playwright David Mamet’s script called for a plane crash, and for Hopkins’ character to fight for his life in an icy mountain lake. And as it sometimes happens, life began to imitate art.

He felt the water creeping into his wetsuit but didn’t think anything of it until he was back in his trailer ten minutes after emerging from the water, dripping, frigid and addled. He began to realize something was very, very wrong; his brain simply wouldn’t function. In the retelling, Hopkins, now 82, remembers the incident like it was yesterday — aside from a few forgotten hours, that is.

“I was so cold. I went back to my trailer and thought, ‘Where am I?’ I couldn’t remember if I was in Canada or Switzerland. It was a little like being drunk,” he recalls, summarizing those lost moments when he was airlifted to a hospital in nearby Calgary and diagnosed with hypothermia. “I lost part of my memory for a few hours. Not severely, but I couldn’t figure out what time it was; I had lapses of moments. It was unnerving. The doctor said, ‘You’re OK, but don’t do this again. You’re not a spring chicken anymore.’”

Hopkins agreed. Personally, he has since played it safe. Professionally, well, that’s a different story. Twenty-four years later, he willingly — eagerly, even — decided to take on a character who’s submerged in his own mind. The Father, out Dec. 18 from Sony Pictures Classics, revolves around a British octogenarian’s descent into dementia.

When Hopkins read Academy Award winner Christopher Hampton’s adaptation of lauded French playwright Florian Zeller’s internationally acclaimed play, he knew, come hell or icy water, that the title role had to be his. It was there in every fiber of his being, a similar sensation to one he’d had 30 years earlier when reading the script for The Silence of the Lambs — which, of course, resulted in his iconic Oscar-winning turn as Hannibal Lecter. Both were parts he was born to play.

“I had no qualms about it at all; I just knew I could do it,” he says now, over Zoom. “You don’t have to do any tricks or method or any of that stuff when you have a really good script, which this was. I was very keen.”

So he met with Zeller and Hampton at his favored pre-Covid haunt, L.A.’s iconic Hotel Bel-Air, and told them as much. Needless to say, it didn’t take much convincing. In fact, Hampton, with whom he’d worked twice before — on 1973’s A Doll’s House and 1995’s Carrington — had rewritten the title character, Andre, with Hopkins in mind (the character’s name has been changed to Anthony for its silver screen adaptation), and first-time director Zeller agreed to postpone his debut so that Hopkins — who had already signed on to play Benedict XVI in 2019’s dramedy The Two Popes — could star.

Photo Credit: Sean Gleason. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

And slowly but surely, the project, which had its world premiere at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, came together. Hopkins was joined by a formidable cast including Olivia Williams, Rufus Sewell, Mark Gatiss, Imogen Poots and Oscar winner Olivia Coleman (who plays his long-suffering daughter) for a speedy three-week shoot on a simple studio set just west of London last May.

The interactions between Hopkins and Coleman in particular are, quite simply, perfection, he agrees. “We rehearsed about five minutes, but when you’re playing with a really fine actor like Olivia Coleman…you don’t have to act at all. This part was so easy for me, so easy. When you are so prepared, it’s like driving a car; you don’t need to put effort into it, it just takes you over. Whatever I play, whether it’s this or Hannibal Lecter, it’s just me anyway.”

The result of their hard work is a beautifully acted and elegantly written independent film, just as powerful and impactful as its staged predecessor, which won Frank Langella a lead actor Tony in 2016 during its Broadway debut. Lightning might strike for Hopkins here, too, as the film is generating more than a little pre-Oscar buzz. Many critics say that it could result in his second-ever win. And it would be justified. He doesn’t, as a habit, read about himself, so hearing of potential Academy interest is new information. “Is that the latest?” he wonders.

Most actors find validation in Academy approval, but not Hopkins, who has been nominated five times, including this very year for The Two Popes. He enjoys the praise, but he doesn’t need it.

“It’s kind of pleasant, but I don’t hanker after it,” he says. “I’m alive, and I’ve done all the work I’ve enjoyed doing. The last five or six years have been the most terrific years of my life. I’ve done many plays, I played the lead in King Lear with Emma Thompson and Jim Broadbent; I did The Dresser with Ian McKellen, a wonderful actor; The Two Popes with Jonathan Pryce; and now The Father, with this wonderful company, and it’s been the best time. The awards and all that stuff, it’s very pleasant to be regarded, but it’s a bonus. We’ll see what happens. [As I always say]: Ask nothing, expect nothing and receive everything. Life is a succession.”

Photo Credit: Sean Gleason. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

It was absolutely, unequivocally the right time of his life to be tackling such a role. “I’m going to be 83 this year; I don’t have to act to play an old guy — though I don’t feel it, I’m very fit and strong. But it’s not such a big stretch for me to play that part now. The great blessing of getting old is that you don’t have to act anymore,” he maintains.

But the role required much more than an understanding of the aging process. The character Anthony is quietly losing his mind. As his grip on reality fails, his fear is perfectly and poignantly conveyed in every expression; his desperation is palatable as he swings from anger to sadness in the blink of an eye. This character is becoming a broken man as the disease slowly kills him from the inside out, robbing him of his memories, perspective and time. It is exquisite acting from Hopkins.

“The man I play is not at peace. He’s panicking, because he’s losing all of his anchors. He’s a bright man, a bit of an idiot savant, but he’s losing his marbles,” he explains.

Although he personally has very little experience with dementia, he could easily imagine the fear and anger that come with it. Something quite similar happened to his father, Richard, a baker, toward the end of his life.

“[My father experienced] that slowing-down process [that Anthony does in the film]. He had heart disease, he smoked too much and did a little too much drinking,” Hopkins says. “He was a feisty man — a bundle of energy — but his deterioration the last year of his life was pitiful. He would go into weeping jags and [suffered from] depression. He’d get very angry, because that’s what you do when you’re facing death. He wasn’t consumed by his anger, but he was frustrated with his life. He’d get very defensive and go on the attack. But he was a good man. I loved him very much.”

And it’s love that leads to the film’s most heartbreaking moment — the one, in fact, that broke Hopkins. Without giving too much away, it comes, as the hardest things often do, near the end.

“It was a complicated scene,” he says. “The first take was OK; I felt it was good. Florian only did one or two takes in general, but this time, he wanted another. I said, ‘I don’t think I can.’ I don’t know why. I’m not moody in that sense, but this was difficult. I said, ‘Just give me a break.’ [When] I went back on set to do the second take, I saw the empty chair near the bed where my character had been sitting, his glasses and a photograph of his two daughters in past times. And I thought, ‘That’s it. His photograph, his glasses, his book, his pen. I knew what that meant: He’s dead.’ And that got me. That finality is what we all face. We have all our connections, but in the end, it’s all dust. Gone with the wind.”

Photo Credit: Sean Gleason. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

It’s no surprise that a such role would cause Hopkins to contemplate his own impermanence, even though he’s someone who doesn’t have to be “locked in a padded cell” after playing each part. He typically just has “a cup of coffee and goes home,” he says. But this time was different. “I’m thinking about my own mortality every day,” he confides. “I’m not obsessed with death, but I think about it. I think, ‘My god, what a strange thing it is!’”

Perhaps he doesn’t fear death itself, but the mental deterioration his onscreen doppelgänger displays definitely affected him. Several times throughout the course of our conversation, he makes it a point to note that he’s doing everything in his power to stay mentally alert.

“I think we need to take care of our brain, get as much sleep as we can. I read, I learn lines — I mean, I learned the entire script for The Father before we even started. I did King Lear the year before that; I did The Two Popes. I make sure I know all the text — I go over it 150, 200, 250 times, which is kind of obsessive, I know.”

But he’d give anything to avoid his father’s fate, to prevent that slow slide into oblivion. “My father is very much in me, but hopefully I’ve modified myself enough [to be different from him]. I remember those days when he was dying very clearly: that kind of listlessness that I try to fight against. I stay awake. I stay fit because I don’t want to descend into that hopelessness.”

Lest he sound too gloomy, know this: Hopkins loves life. He loves his life. And he doesn’t plan on giving up on it anytime soon. “I could go on for many years, but you never know. [Either way], I have a long time to die, and it’s a big sleep. Mostly I just think about life, [with] a contented state of mind, really, because I think I have had the most incredible, amazing life, beyond my dreams. It’s like somebody else wrote my story. I don’t know how I got here, you know? I look back over my life and I think, ‘Well, this is extraordinary.’”

WHEN HE WAS A BOY GROWING UP IN PORT TALBOT, WALES, LONG BEFORE HE WAS DISCOVERED BY SIR Laurence Olivier, knighted by Queen Elizabeth II and holding his first Oscar, Anthony Hopkins hated afternoons. He found them depressing. Don’t ask why — he doesn’t really know. But now, oh now. How things have changed.

“I love mornings best, but I really like all day now. I prefer to wake up and live,” he says, minutes after greeting us over Zoom with a big, beaming smile — the kind that reaches his eyes — a little wave and a bright, “Hi! It’s Tony!” But does he really know the time? Hopkins hasn’t left his Pacific Palisades pad in nearly nine months, since the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. Morning, afternoon and night have all blended into one long day. And he couldn’t be happier about it.

His home is indeed a confinement, but one of his own making. A 5,778-square-foot gilded, three-story cage where he practices a plethora of artistic pursuits, playing the piano daily, sometimes for a full hour; painting, composing and reading. A quick scan of his bookshelf reveals a variety of authors, ranging from Francis Bacon to Christina Rossetti to David Hockney. He’s currently digging into Charles Dickens’ Bleak House (“There’s some cheerful reading!”) and promises that he will check out The Father co-star Olivia Coleman in Fleabag, which, up until this moment, he had not heard of. (“‘Flea,’ like living fleas? I must look it up!” he enthuses.)

“We have to take care,” he says. “I don’t want to risk [my health]; I just accept that there’s nothing much else to do. My lovely wife, Stella, keeps me in lockdown because she doesn’t want me to get sick. I think, ‘What’s the big deal outside anyway? You walk up the street and go to the same restaurants.’ This is a chance to reset. And I’m having a great time in lockdown!”

As anyone who follows him on Instagram knows, he’s used his quarantine time to maximum advantage, letting the world see the real Anthony Hopkins, in all of his Hawaiian shirt–wearing glory. A “sir” he may be, but one who dances like Drake; swaps funny animal videos with his “coterie” of friends; talks to his cat, Niblo, a 10-year-old stray he rescued in Budapest, like a human; admits that his greatest pleasure in life is breakfast (specifically, protein shakes and oatmeal); shares goofy videos of himself playing classical piano while wearing a Halloween horror mask; and who, at the age of 82, decided to launch a fragrance collection for the hell of it (and also to do some good: sales of his Anthony Hopkins Fragrance Collection eau de parfum, candles and diffusers will benefit the nonprofit No Kid Hungry, an attempt to “bring a spark of light into the world”).

At this point in his career, could we expect anything less? Sure, he’s starred in a slew of Merchant Ivory period pieces, like The Remains of the Day and Howard’s End, but lest we forget, he’s also the Marvel Universe’s Odin, and he doesn’t mind playing with robots, as he did opposite Mark Wahlberg in Transformers: The Last Knight and on HBO’s dystopian dramatic series Westworld. This is also the man who completely transformed himself into radically different historical figures, including former presidents Richard Nixon in Nixon and John Quincy Adams in Amistad, artist Pablo Picasso in Surviving Picasso and filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock in Hitchcock. Basically, no one should be surprised that he continues to surprise with his cinematic choices. The man knows what he’s doing — as his Oscar win, five nominations, seven Golden Globe nominations, two Primetime Emmy Awards and three BAFTAs suggest.

We suppose he’s grateful these days that he wasn’t “bright enough to do anything else.” (His words, not ours.) “I was a terrible schoolkid; I couldn’t play sports. This has been my hobby all my life, acting. I stumbled into it and I thought, ‘This beats working for a living.’” His eyes twinkle. “That was Robert Mitchum’s favorite quote. I’ve adopted it.”

Don’t let him fool you: acting has always been a calling, not a fallback. Several years after graduating from the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama in Cardiff, he was spotted by Sir Olivier, who invited him to join the Royal National Theatre in 1965. His first major film role, Richard the Lionheart in 1968’s The Lion in Winter, followed soon after.

“I knew from an early age what I wanted,” Hopkins says now. “It was something beyond ambition. I knew there was something I could do that maybe somebody else couldn’t, and I had a great mentor in Laurence Olivier. I worked with some incredible people, like Peter O’Toole and Katharine Hepburn. I’ve been very fortunate.”

What he really wants now, right now, is continued serenity. He’s having a grand old time at home, but as much as he’s aware of what’s happening outside, he finds that being assaulted by its negativity so regularly is killing his vibe. And so, for the past week, he’s been on a media strike. “I know the world would say I’m being an ostrich, but it’s too much noise,” he explains. “You think, ‘What on earth are we all talking about?’ Everyone’s got an opinion about everything! I can’t listen to it. I haven’t watched the news for five days now, and already I feel like a different person. I really do. I go through patches where I won’t read or watch anything at all. I get so sick of those same faces blabbering on about this and that. We’re addicted to bad news. I just want a peaceful life.”

What he refuses to do, he says, is give in to cynicism. “I think, ‘Well, this is the world. None of us is perfect; we all make mistakes. Governments screw up, wars start, that’s the state of humankind.’ I was playing some Brahms and Rachmaninov this morning, and I couldn’t help but think what extraordinary genius there was in these great musicians and composers, yet how the same nations that produced them produced such colossal warfare. But that’s the nature of human beings. We’re aggressive, hardwired killers on one side and then tremendously creative on the other. Yet I don’t despair of us; I think we have so much potential. Being cynical is being cowardly and a waste of time,” he declares, before musing, “Of course, I do get cynical sometimes, but I think, ‘Oh come on, forget it. The best thing to do is weather it. Just do the best you can. You have to believe in the present because the rest is an illusion anyway. Live life, say yes and get on with it.’”

And what a life he’s had.