Around midnight one winter evening in 2013, Ethan Hawke made the trek home to Brooklyn from Lincoln Center, where was starring as the title role in Shakespeare’s Macbeth―to to find his wife of five years, Ryan, at their kitchen table, tears streaming down her face. Before he could ask her what was wrong, she closed the script resting in front of her and said, “You have to do this movie.”

His curiosity and questions were met with silence. All she would say was, “Just promise me you’ll do it.” His response: “I’m not promising you.” Needless to say, his wife got her way. And thanks to Ryan, theatergoers, too, will be crying into their popcorn should they choose to see Maudie after its release on June 16. The Sony Picture Classics’ indie weeper is based on the true story of Maud Lewis, an arthritic Nova Scotia woman who became one of the most beloved folk artists in Canadian history. But instead of a rambling, meandering biopic, Maudie is a beautiful little story about love blossoming between two unlikely, lonely people.

Truthfully, his wife’s reaction was only one of many reasons Hawke accepted the supporting role of Maud’s husband, Everett Lewis. For starters, Nova Scotia holds a special place in his heart: he’s owned property there for over 20 years and refers to the province as his “sanctuary.”

Then, there was the allure of working with Sally Hawkins. He knew, just by reading the script, that the British actress best known for her work in Mike Leigh’s Happy-Go-Lucky would do magical things with Maud. “I felt similar when I readTraining Day, knowing that Denzel [Washington] was going to play that part—‘That’s a great role and that actor is going to know what to do with that role and play that part right,’” he says.

There was also Maud herself (although initially unfamiliar with her art Hawke says he was “very moved” by its simplicity and beauty). There was working with a female director, Aisling Walsh, for only the third time in his almost 30-year career. And there was the challenge of it all. “As the years progress, I’m getting more and more interested in trying different types of character work, and I rarely get offered parts like this. Maybe when I was younger, I didn’t have interest or believe that I could do it,” he muses. “And movies like this don’t get made very often.”

He was also fascinated by the subtext of Maud’s story. “There is something very female about it that is beautiful to me; how strong and how tough people can be, and how much of your life is in your mindset,” he says. “This is somebody who was given shit—poverty, her whole family was horrible to her, her husband marries her because he wants somebody to clean his house, and so that he can get laid every now and again. He likes his dogs more.”

Brutal, yet truthful. This dichotomy—the diversion from traditional storytelling—fascinated Hawke with its raw honesty. “By the end of the movie, [Everett] is just a guy whose gob smacked in love… but he didn’t come there on the easy road. Most people fall in love when they’re young, and it’s all about sex. [Maud’s] goodness as a person—her innate, intrinsic goodness—had a power over him. That’s a story I hadn’t seen,” he admits.

Playing the brusque and, at times, cruel Everett, yet identifying with the singularly optimistic Maud gave him some proper food for thought: “I love, if you’re in a long relationship, how the power is always changing. It’s fun to watch people grow and mature and change, seeing who’s in charge and seeing the dynamic shift. At the beginning, Everett was basically like, ‘You’re my maid,’ and by the end, he’s feeding her, preparing her canvases, cleaning for her and her biggest champion. He’s out there selling her work. Watching that transition, which happened over 30 years, was really kind of remarkable.”

With Everett, Hawke is also enabling a change for himself, a transformation in his career. “My whole life previous to the last five or six years, I hadthis expression where I considered myself to be a ‘first-person actor.’ There are actors I love—Daniel Day Lewis, Vincent D’Onofrio, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and a bunch more—who I would call ‘third-person actors’; they really create a character. Then there’s somebody like Paul Newman, for example, who is a ‘first-person actor’. He brings himself to the role. He’s different in Cool Hand Luke than he is in Hud, but it’s different parts of himself.” He elaborates, “I like to write, so I liken it to writing, where there’s a first-person narrative and a third-person narrative. A few years ago, I started trying to do more character work, more third-person stuff. [This role] is a continuation of that for me. I’m an artist and I relate to Maudie more, so I came to Everett as a student, really. I wanted to get inside his skin and understand him.”

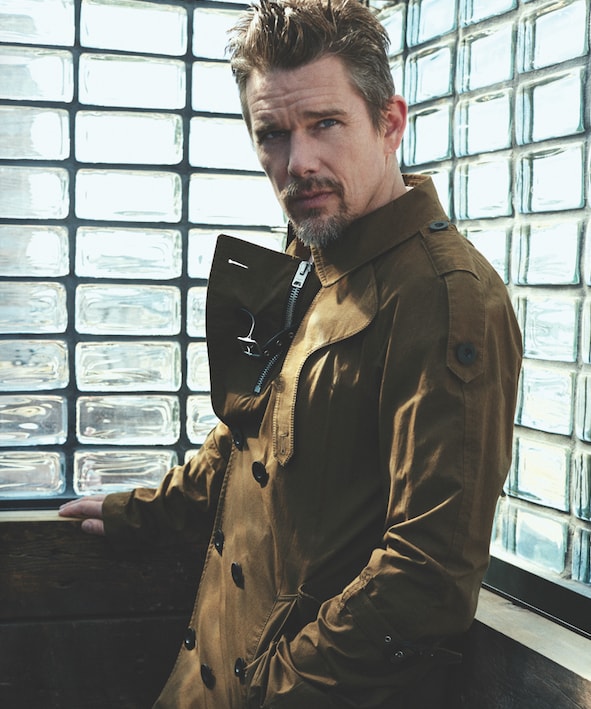

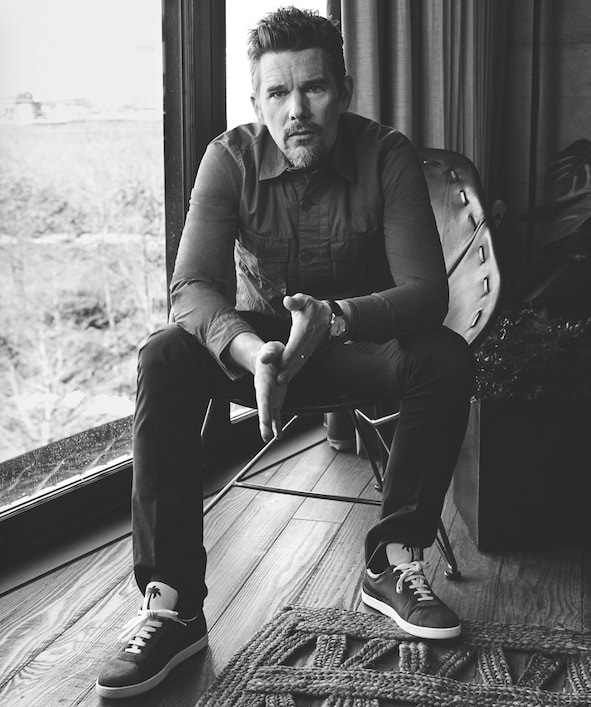

Photo Credit: Michael Schwartz

In the end, he applied both third-person and first-person skills to the character. He identified Everett by becoming him, using his own personal experiences to do so. Everett Lewis was an unhappy, unpleasant loner who somehow learned to love. Yet, in Hawke’s opinion, is it better to have love and lost than never loved at all? “I always feel that we all come to the same answer: that life is meant for living. Is he in more pain with her gone than he would have been otherwise? Yeah, he is. Life is hard. No sooner do you care about something than it’s gone. It’s always changing.”

He references his own life, explaining, “[I’ve learned this] even watching my kids grow up. I have an 18-year-old now and a five-year-old. I know how temporary this five-year-old thing is. When my oldest was five, I thought she’d be five forever. And in a way, she is. But she’s very different now. She’s a young woman. That five-year-old is gone.” He continues, “She’s still really interested in what I do and she still talks to me, but then there will be a time [in the future] that she talks to her husband instead. It does teach you how the moment is constantly changing. We’re losing all the time, and we’re also gaining all the time. To love is to lose love. But you move on. You have to.”

ART TAKES MANY FORMS

“People often ask me about acting,” Hawke announces. We can imagine why—he has been working in the industry for over half of his life, after all. He started out at age 15 in 1985 with Explorers, a science fiction family film, but it was the 1989 drama Dead Poets Society that fully launched his career. Now 46, he has been acting for over three decades, accruing four Oscar nominations and a Tony nod.

Acting is his career. He is exceptionally good at it, has become famous from it and owes everything he has to it. But is he passionate about it? That’s up for debate. “Acting for me has become my profession, my livelihood, how I pay for my kids’ school, how I pay for health insurance; it bought my house and my vacations and it’s become a real craft,” he says. “I really work at it. It’s my job and I enjoy it, but the other elements of my artistic life—directing, writing, doing projects like a documentary or dabs in journalism—they really turn me on the way a hobby does to other people.”

He pauses a moment to lament on the patronizing sound of the word ‘hobby.’ If he had to choose a word to describe his artistic pursuits, this would not be it. ‘Passions’ would be more accurate. He has dabbled in screenwriting (receiving two of his four Oscar nods for Richard Linklater’s Before Sunset and Before Midnight), written a novel, graphic novel and children’s book, founded a theater company, profiled Kris Kristofferson for Rolling Stone and directed films, including his documentary directorial debut

Seymour: An Introduction in 2015, which followed the life of the legendary pianist and piano teacher Seymour Bernstein. Obviously, Hawke is a real artist—and one who experiments across mediums, at that. He loves the controllable nature of writing, citing it as “orderly and private,” but loves directing for completely opposing reasons: “because it involves being part of a family, or a team. When you’re directing, you get to hire everybody. It’s all people you like.”

He recently wrapped production on Blaze, a drama he co-wrote and directed about the life of country western musician Blaze Foley, and describes the experience in such a way that makes it sound like a big old southern barbeque. “It was like, ‘Guess what? The [director of photography] is a guy that I love. I hired him myself. Everyone is someone I like. It’s not someone that some jerk [who runs a studio] thinks has talent. The sound guy that I worked with three years ago that I liked, he’s coming. The whole thing feels like a party,” he gushes. “At the hotel room where we were filming in Louisiana, it was like a wedding. It was all my friends. That aspect of it is what I love, and probably why I’m not a professional film director.”

Not that it matters. Directing is a pastime, not his day-to-day profession. “In Seymour, [the pianist] says, ‘There’s something really beautiful about being an amateur in the best sense of the word,’ and I really believe that—doing something because you believe in it, but not for professional reasons. That’s how I feel about directing. I do that because I love it and it turns me on.” He pauses and adds, “I think acting used to be like that for me.”

Photo Credit: Michael Schwartz

He hastens to explain his statement in a way we can understand, and we do: something you love doing, no matter how much, always becomes slightly stressful, less fun, when it’s a necessity. “Acting is really exciting and dangerous. To do it well, you kind of have to jump down some weird rabbit hole. When the muse arrives and leaves, when it works and when it doesn’t, is mysterious to me. [My love of acting] never stopped—it transformed. I didn’t wake up one day and go, ‘Oh no, I have to pick up my suitcase and hock my wares.’ It’s not like that. [Acting and I are] so closely intertwined. It’s my trade and it’s not fun the same way because, if it goes badly, then there’s things at risk.”

He explains, “I’ve got bills. I want to be a good actor. I don’t want that to sound crass—I clearly love it and I try really hard not to ever do mercenary things. I want to put good, meaningful, substantive art into the world. That’s my job, and I’ve been able to do that and take care of my family, which is a super luxury. But it’s not fun the way water coloring in [my] room on a Sunday afternoon when the snow is falling is fun.”

Not to worry, though: Hawke has no intention of quitting his day job any time soon. In 2016 alone, he starred in five films, including Antoine Fuqua’s mega-watt The Magnificent Seven reboot, alongside Chris Pratt and his old pal Denzel. This year, in addition to Maudie, he’ll appear in Paul Schrader’s thriller First Reformed with Amanda Seyfried, and Luc Besson’s sci-fi thriller Valerian. He will also start production on the Judd Apatow-produced romantic comedy Juliet, Naked with Rose Byrne come summer.

He admits that he’d like to do more comedies moving forward—but, unlike many of his peers, Hawke doesn’t think he’ll make the transition to television (despite an unwavering love for Game of Thrones). “I always find the goal of great cinema is to entertain you and leave you with something, and leave you better than when you walked in. A lot of TV does feel like I wasted some time. I get offered TV and I want to know how it’s going to end and then they say, ‘We’ll see if it’s successful.’ It doesn’t have an end—it doesn’t have a middle for fuck’s sake—and my brain doesn’t work that way.”

Instead, he’d rather focus on more projects that bring him joy—even if they’re bringing in more of an emotional reward than a financial one. Such was thcase with his first graphic novel, Indeh, which debuted at number one on theNew York Times’Bestseller List for Hardcover Graphic Novels. Hawke’s eyes light up and he looks like a little kid when he explains how receiving six new drawings from illustrator Greg Ruth every week would send him into tailspins of excitement. “I love two-dimensional things,” he announces. “The frame of a film shot. I love drawings.”

Unexpectedly, he stops, and continues almost musingly: “The more I think about it, the more I think I might be dyslexic. I’m starting to learn a lot about dyslexia and I think, when I was growing up, that word wasn’t so common. Part of why I liked graphic novels and comics so much is that they helped me read.”

In addition to a love of books, he gifted at least one of his children another shared interest. His eldest daughter, Maya, an 18-year-old Julliard attendee, has also inherited a love of the arts from Hawke and his ex-wife, actress Uma Thurman—though he notes that 16-year-old Levon is the complete opposite: “My son says things like, ‘I want to do a job where, if you’re good at it, you keep getting promoted.’ He’s watched the roller coaster ride of being a professional actor, where sometimes you get a lot of work and sometimes you don’t for a long time.”

The latter can be especially true in Hollywood with age. “Nobody tells you what a young person’s game it is,” he laments. “There are a lot more parts in mainstream movies when you’re young. I didn’t realize when I was younger, 18 to 25, that virtually the whole movie industry is geared to entertaining you. [Now] I feel like an old pitcher; when your arm stops being as fast, you have to figure out other ways of getting people out. I followed Peyton Manning’s career obsessively for years. There’s so much talent there, but the body is giving out. He adds, “Luckily for me, “I’m not an athlete.”

PASSION + EXPERIENCE

Post-shoot, Hawke is meandering around the new 1Hotel Brooklyn Bridge’s Skyline suite. He’s buoyant, restless, full of energy. When we tell him it’s time to begin the interview, he’s ready to dive right in.

“Trump sucks!” he yells like a gleeful, impudent, little kid caught with his hand in the cookie jar. So this is how it’s going to go down, then. Game on, sir. We’re ready, too.

“The only positive to having a complete carnival barker as a president is seeing how energized young people are for the first time. Because I have an 18-year-old now, I’m getting to see all these 18-year-olds who grew up for their whole conscious lives with Obama as President, so they have this idea that everybody cares about the environment, equal rights—this Benetton view of the universe. They didn’t have any sense that there was something worth fighting for,” he says, noting, “But I think, if we can manage to minimize the damage that happens in the coming months and years, if we can survive it, I think you’ll see a totally energized generation of young people who will know that all actions have reactions. That’s my one takeaway.”

Hawke is from the blood red state of Texas. But, for most of his adult life, he’s been living in New York City, and it’s hard to be anything but liberal when you’re living in a place with so much diversity. That said, he can’t completely ignore his roots, and admits that he’s most disappointed, politically, with the Christian community. “If they withdrew their support, it would be very meaningful. I was raised a Christian, baptized and confirmed. It was a huge part of my childhood, good Christian ethics, Sunday school, the golden rule—‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’ I think that Trump has done a good job of playing people and using them. ‘Oh, you’re against abortion? I’ll do that for you.’ They become one-issue voters. They don’t see that this person doesn’t represent their belief systems at all.”

To many, Trump symbolizes affluence, says Hawke. But it’s all smoke and mirrors, a fancy parlor trick. “They see those gold letters, but what they don’t realize is that it’s all tin. Those letters aren’t really gold. He’s this old-fashioned money lender weirdo who needs to be thrown out of the temple, you know?” he adds with a laugh. We then note our disappointment and confusion in the decidedly anti-feminist southern females we’ve met recently, all of whom voted for Trump and shrugged away his sexist comments. Hawke, being from the south himself, can explain this: “The biggest surprise is the power of young women growing up in an extremely misogynistic society that feels familiar and good. They recognize it. They don’t want to ask more of their leaders. It was refreshing for them to see the men they knew. It was a weird thing.”

He predicted that the election might not go as expected because of Blaze,as it happens. Flying back and forth between Baton Rouge and Brooklyn on a weekly basis gave him significant insight into the political leanings of both sides. “I was shooting in Louisiana when the whole ‘pussy grab’ thing happened. It was fascinating to see the indignance in New York [while the] people in the south just thought it was funny. I knew it was a lot more dangerous than other people knew. That ‘pussy grab’ thing was a real indicator. I’m like, ‘He isn’t done.’ A lot of the country really didn’t care that he said that.”

Photo Credit: Michael Schwartz

Trump’s win was part of the reason behind his decision to immortalize Blaze Foley on film. “Blaze came out of being hypnotized by country music”—it’s true, Hawke’s first concert was Willie Nelson’s Fourth of July Picnic—“and having a fascination with the definition of success,” he says. “This country is so obsessed with success and the perception of success and accumulation of wealth. Everybody understands that money doesn’t make you happy, but that’s what they dedicate their entire lives to doing. Why is it so hard not to be caught up in that game?”

And so, he threw a bone to the underdog. “Blaze is about a guy who is not a success. Every biopic is about someone who became wildly successful, but this movie is about a guy who literally never had a record come out during his lifetime. But he should have, and lots of people should have. I’ve grown up with tons of great actors and wondered, ‘Why didn’t that career happen?’”

He quickly answers this himself: “It’s usually self-destruction. People not thinking they deserve success. The biggest enemy isn’t a cold, harsh world, it’s usually an inner demon. You usually cut your own heels. I’m kind of obsessed with finding the answer to that question. I mean, look, it really even relates to who we elected president. We have this American, knee-jerk response to wealth as if it’s meaningful or interesting or represents somebody who’s led a meaningful, worthwhile life. It usually doesn’t. A lot of drug dealers and guys on Wall Street are rich.”

There are many things more meaningful than money to Ethan Hawke. “This is going to sound corny to say, but if you really boil life down, it gets really simple and cliché.” He candidly reveals, “What brings me the most joy in my life is when things are going really well with my wife.”

He has been married to Ryan Shawhughes since 2008 and they now have two daughters, Clementine Jane and Indiana. “I feel like all things are possible when that central relationship in my life is really happening mutually; that the marriage is really turning her on and good for her. It’s the engine of my life. It drives everything else. [It’s a] huge, defining aspect of your life and, when that is working, you know it’s just awesome. I just love it. I’m old enough now to know that making it work is about me and about what effort I’m putting in and how I’m taking care of [the relationship]. It’s the best part of my life. Love is a great, great feeling,” he concludes, before smiling and adding, “I know it’s kind of uncool to say nice things about your marriage.”

We beg to differ. In fact, we’re totally on board with the life—and love—lessons Hawke is trying to teach his children. “When my kids ask, ‘Am I going to be famous? Am I going to be successful?’ I say, ‘I hope you have a great love life. I hope you have a great partner. Because, if you have that, everything else is going to be fine.’”

These are also lessons he is passing down from his mom, Leslie, a charity worker. “My mother used to say, when I’d worry about the future, ‘The truth is, there are only two things that are going to happen: you’re either going to handle things well and be happy, or handle things poorly and be miserable.’”

He thinks about this concept so often that he even references it in Rules for a Knight, the New York Times bestselling children’s book he and his wife released in 2015. It includes the Native American legend “Two Wolves” that illustrates an internal struggle between right and wrong, good and bad. When an old Cherokee teaches his grandson about life, he cites a terrible fight between two wolves. The grandson asks, “Which wolf will win?” The grandfather responds, “The one you feed.”

Hawke explains, “One wolf is greed and self-concern and fear and anger and jealousy and conceit, and the other wolf is empathy, love, brotherhood and joy. If [there was] a central thing that I think about, [it] is trying to feed the right wolf every day.”

He does this in a variety of ways. “If you spend time with people that you love, if you spend time with people that you admire, if you spend time doing things that you love, good things generally happen. Good things come, friendships develop and life takes care of itself. But if you spend time away from love, or if you spend time away from people that make you happy or aspects of yourself that make you happy, or indulge aspects of yourself that make you unhappy, they both can catch fire—the dominos fall. Life can get harder the more you feed the wrong wolf, the more you let the wrong wolf come to a head.”

He admits it, though: he hasn’t always fed the right one. “It’s not that I haven’t made bad decisions in my life, because Lord knows I have… but everybody likes to say [regret is] part of life. It’s like, ‘Well, part of my life would have gone a lot better if I hadn’t said that stupid thing.’ That’s where my regrets are,” he admits. “I don’t mind learning a lesson, but it’s a drag if I have to learn it 15 times. That’s what I feel like now. I don’t need to learn that lesson now. I want to have learned that. It’s always hard. I have tons of regrets, but… you don’t want to say them because they’re embarrassing, and behaving badly is not something one enjoys putting in print.”

He stops for a second, seemingly to think about what he really wants to say, before confiding, “I definitely have tons of regrets, and pretty much they all revolve around being selfish, when [I] couldn’t see outside [of my] own immediate needs. I have things I wish I didn’t do and mostly things I wish I didn’t say. You can’t unsay things and, a lot of times, you say things that aren’t true [ just] to hurt people. Actions have reactions and relationships can only handle so much weight.”

But when Hawke feeds the right wolf, he says, it’s all gravy. And, as he’s aged, that wolf is hungry for family and art. “The only thing I used to really care about was this great guitar I had, a ’52 Martin that I’ve had since my early 20s. I loved it so much that I used to say it was the only thing I would want to pull out of a fire. But now, I really don’t care. I really do like the guitar and everything, but I would only care about my wife and kids. Life is what’s really valuable, right?”

Life, and a wealth of creative freedom, might be more accurate—and he knows it. “Most people can’t spend part of their year working on a graphic novel that’s not going to make any money, but because I have a day job that’s financially lucrative, if I want to stop what I’m doing and write an article on Kris Kristofferson, I can do it. If I want to make a movie about Blaze Foley, I can do it. Creative freedom is just an unbelievable luxury. I’ve lived an incredibly privileged life that way.”

And, really, what’s the point in feeling bad about his good fortune? “The only way not to be crippled by guilt is just to keep putting good things out in the world. It’s the only immediate way I know to give back. It’s why my wife felt it was so important to make Maudie. If you’re not going to do it, who is? You’ve got to put it into the world.”

SHOT ON LOCATION AT 1HOTEL BROOKLYN BRIDGE