When Los Angeles media scion and former L.A. Times publisher Otis Chandler passed away in early 2006, only a small percentage of those who mourned him wondered what would become of his collection of prewar American automobiles. Fewer still wondered what would become of the building that housed the collection some 60 miles north of L.A., in breezy seaside Oxnard. The answer to that little-asked question surfaced on the evening of April 15, when one of Chandler’s friends and fellow automotive enthusiasts, Peter Mullin, reopened the facility as the Mullin Automotive Museum.

Just a cursory glance inside reveals the depth of change that the building has undergone since Mullin, a successful Southern California businessman and noted collector of prewar French cars, set about redesigning the facility with a new philosophy. While Chandler’s collection had been mostly pared to American makes like Packard and Cadillac, Mullin’s collection is flush with the most opulent and exquisitely designed coachbuilt cars of prewar France. Delahayes, Bugattis and Talbot-Lagos with bodies by Figoni et Falaschi, Chapron and Van Vooren now grace the main floor of the Oxnard museum.

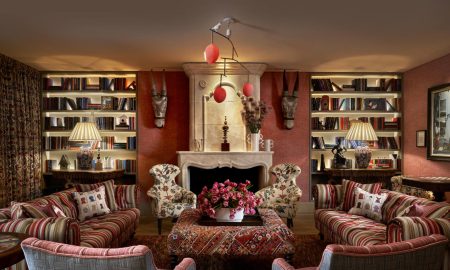

The cars only represent one component of Mullin’s guiding mission, though. Also featuring a substantial collection of housewares, furnishings, and decorative art, the Mullin Museum promises to be the first publicly accessible museum in America dedicated to the Art Deco movement that influenced art and design between 1925 and 1939. Though his facility is labeled an automotive museum, Mullin hopes to present a more comprehensive vision of the Art Deco culture of prewar France.

“The center of Art Deco happened in Paris in the late 20s and 30s and it impacted sculpture and furnishings, graphics, vases and crystal, and haute couture,” explains Mullin. “It was the birth of a way to think about design, and the cars were certainly the driving centerpiece of all of that. The [original] concours d’elegance wasn’t about going to look at a car, it was to look at an entire package of a beautiful woman in a beautiful dress with her Russian Wolfhound standing by her side, with her luggage, her hat, and a car. Sometimes the car was painted to match the woman’s dress and sometimes the dress was made by a couture house to match the car, but when you went to a concours d’elegance, it wasn’t to look at cars, it was to look at a presentation.” Echoing this notion, Mullin offered guests just such a presentation at the museum’s inaugural event. Models in period couture dresses strolled amongst the million dollar cars, contributing to the multi-faceted cultural tapestry that Mullin seeks to re-create.

At least one major player in the collector car business has embraced the museum’s mission. Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S., the VW-owned company that has rekindled the Bugatti legend, has taken the unusual step of lending its four most important prototypes to the museum for display. The EB118, EB218, 18.3 Chiron, and Veyron prototype showcase the company’s evolution from the Italian produced EB110 of the early 90s to Bugatti’s current production Veyron supercar.

The Bugatti loan embodies one of many different states of presentation that the museum hopes to offer. While some cars, like Mullin’s prized 1938 Talbot-Lago T-150 C SS “Teardrop” Coupe, feature concours-quality restorations, others, like former pieces of the famed Schlumpf collection, are completely unrestored and unmolested. The furthest extremes of this spectrum are represented by two radically different Bugattis. One, a 1925 Bugatti Type 22 Brescia Torpedo, was recently removed from the bed of Italy’s Lake Maggiore, where it had been laying on its side under 173 feet of water for 75 years. One side of the car was miraculously preserved by the mud in which it lay; the other has been stripped bare by decades of exposure.

Mullin’s Bugatti Type 64 sits at the other end of the spectrum. The car has the unusual distinction of never having been built, that is, by its original creators. The Type 64 had been designed to be the next iteration of Jean Bugatti’s wildly popular Type 57, but was never built due to his death in 1939. Inviting the collaboration of Stewart Reed, the chair of the Transportation Design Department at Art Center College Of Design in Pasadena, as well as a group of lucky design students from the college, Mullin utilized original Bugatti blueprints and design drawings to commission the construction of the Type 64 from scratch, employing the utmost in authentic materials to finally breathe life into the dangling legacy of Jean Bugatti’s genius. “It shows that, as a museum, we are trying to stay very involved in the conversation about style and design, and its relevance today,” comments curator Andrew Reilly.

Ultimately, Mullin hopes to increase awareness of the various disciplines addressed in his museum so that enthusiasts of one type of collectible might come away intrigued by another. “A lot of people will come here because they want to see the Art Deco displays, the furniture and the sculpture and the graphics,” he reasons. “And so a lot of people will come here really not caring about cars, and then will leave caring about them.” But beyond making converts to the evolving idea of the automobile as art, Mullin hopes to distance the motorcar from the negative role of environmental monstrosity that has been cast by many critics. To that end, he has overhauled the Oxnard facility so that it is completely self-sufficient in terms of its power needs. All electrical fixtures have been converted to energy-saving units, and 100% of the building’s power will eventually be sourced from solar panels on the roof and nearby wind turbines.

“One thing that intrigues me is that people, particularly environmentally sensitive people, think of the automobile as a disaster,” explains Mullin. “Breakthroughs in automobile design and in energy associated with the automobile are something to be embraced, not to be abhorred. I think an automotive museum that’s a green building that is completely energy efficient, and is generating 100% of its energy use, allows people to kind of rethink that a little bit, and actually ask themselves, ‘what was the role of the automobile in the development of the United States specifically, and the world generally?’”

For more information visit www.mullinautomotivemuseum.com