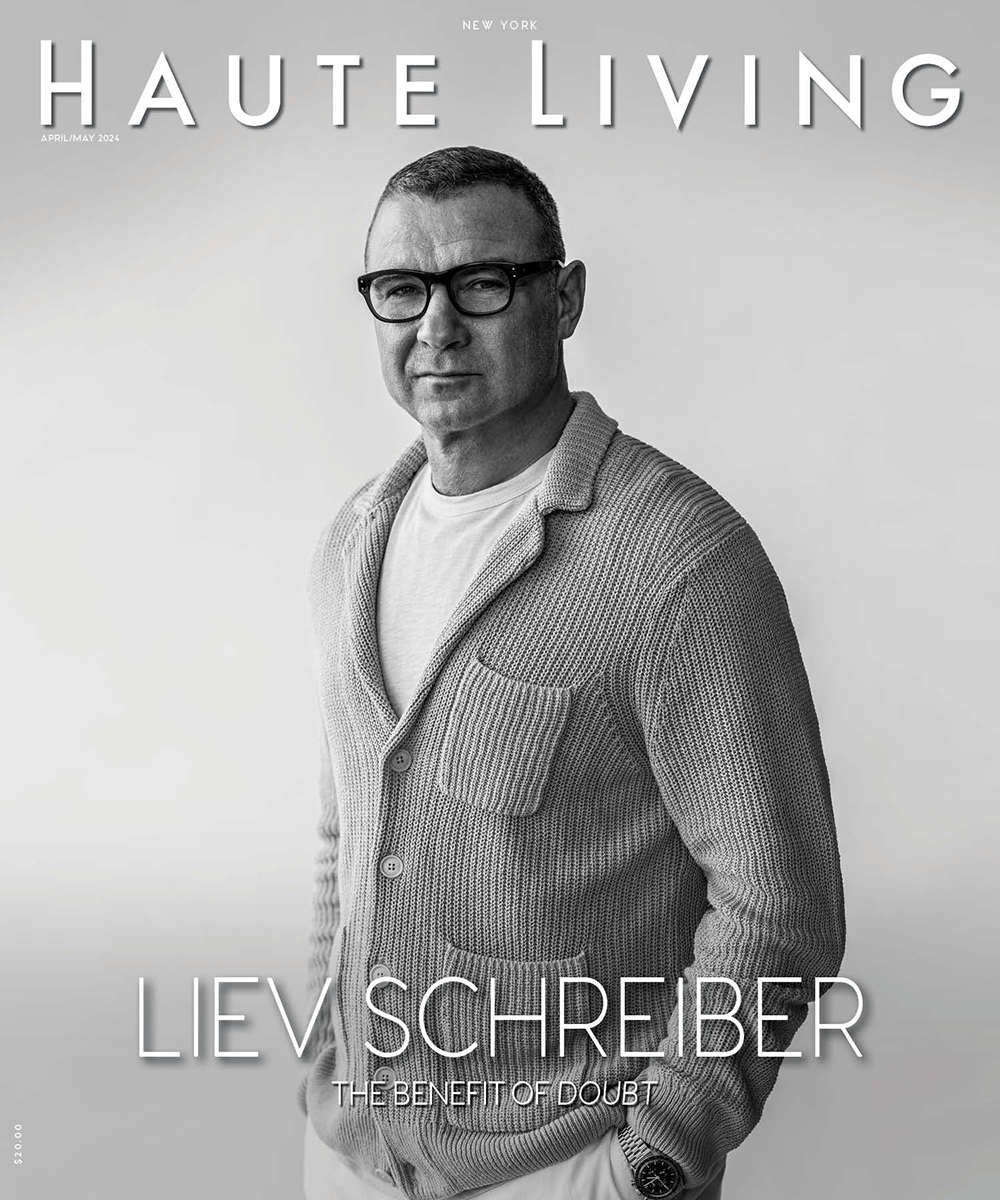

Liev Schreiber Gets Philosophical On The Benefit Of “Doubt”

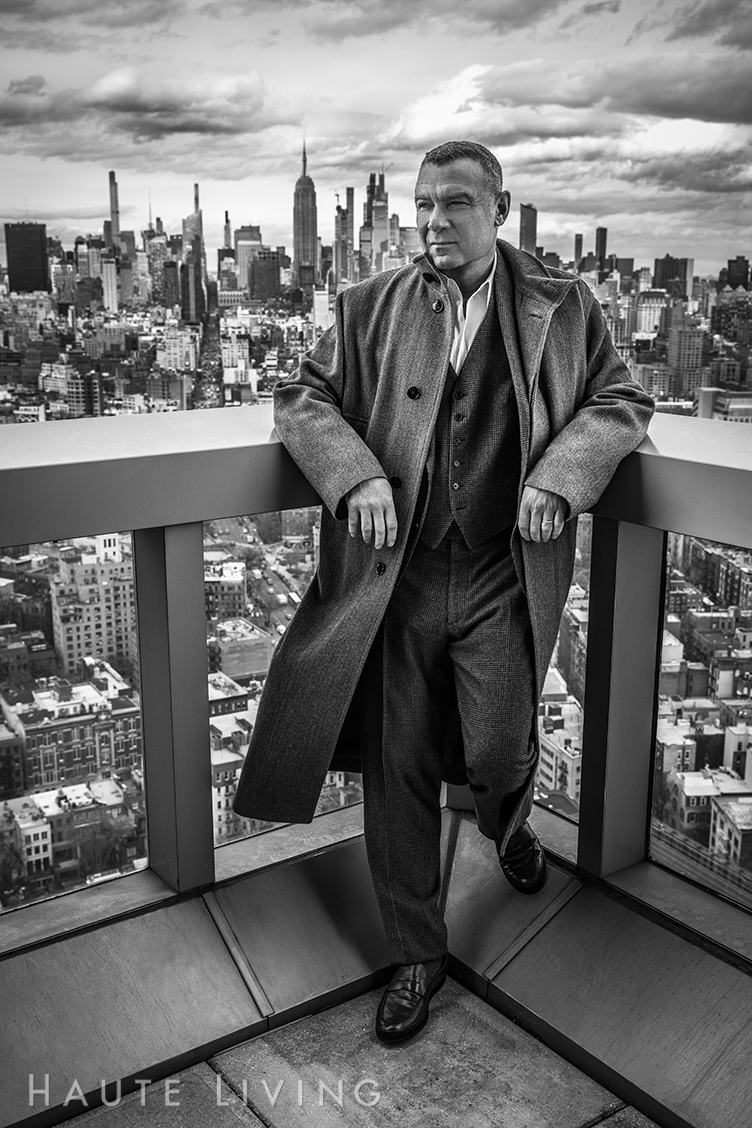

SUIT: Ralph Lauren

COAT: Lemaire, available at Saks Fifth Avenue

Photo Credit: Scott McDermot

BY LAURA SCHREFFLER

PHOTOGRAPHY SCOTT MCDERMOTT

STYLING ERIN MCSHERRY

GROOMING KUMI CRAIG

SHOT ON LOCATION AT THE DOMINICK HOTEL, NY

Liev Schreiber is a big proponent of reading reviews — the good, the bad, and the ugly. Rather, I should say he was… until now.

His hesitation has nothing to do with the fact that his current project, the Broadway revival of Doubt: A Parable, lost its leading lady, Tyne Daly — hospitalized with a medical condition less than a month before opening night — or that he had to find immediate chemistry with her replacement, Amy Ryan. No, it was one, small but mighty word that set him back from seeing the predominantly glowing appraisals of his turn as Father Flynn in John Patrick Shanley’s Pulitzer Prize- and Tony Award Best Play winner.

“I got scared off by one [review in particular], which said that I was old,” the 56-year-old Tony winner confesses. “I didn’t want to read any further than that because I could immediately feel that [comment] hurting my feelings. But also, I think that they were right — not that I was too old in life, but that I was too old for the role, and in many respects, that made me feel old. When something gets inside my head, it doesn’t go away. It never bothered me when I was younger, but now is a different story.”

Not knowing how others assessed his performance was a departure from his typical M.O. “I usually do read the reviews,” he insists. “I’ve always been that kind of person, in fact. I always want to know everything. I’ll always go see every other production of the thing that I’m doing. I like to use the library at Lincoln Center because they have a video of every show that’s ever been done, so you can go and see what other actors did, and how other versions were directed. I believe in the idea that most art is theft, and it’s almost impossible to duplicate what someone else did, but if they have a good idea, I’m all for taking it.”

It’s funny: had Schreiber not been thwarted from his regularly scheduled programming, he might have seen just how effusive critical praise of his Roundabout Theatre Company production has been since its March 7 opening at the Todd Haimes Theatre.

Regardless, he is personally pleased with the performance, despite its rough beginning, saying, “I think it’s gone incredibly well, which is really a testament to Amy and how quickly she got up to speed.” It is not just Ryan, who plays Sister Aloysius to his Father Flynn, but their chemistry together that has been deemed “electric” and the Scott Ellis-directed revival “excellent,” among other positive appraisals of the play, which revolves around a non-nonsense nun (Ryan), who suspects a charming, charismatic priest (Schreiber) of having an inappropriate relationship with a student. Without evidence, she is forced to distinguish fact from fiction. Doubt, which is set in the 1960s, examines how people manage feelings of uncertainty — a still-relevant topic in today’s political climate. Playwright John Patrick Shanley shows that things fall apart when people focus on being right instead of discovering the truth.

Father Flynn is a plumb part for any true thespian, which is why Schreiber ultimately signed on to play it despite knowing that, on paper, he was too “old” for the role. The character, after all, a man from a working-class family in the Northeast, is described as a man in his late thirties. But together with Daly, they had written a new narrative, one where his character, in his 56-year-old body, represented a new idea, while Daly, at 78, symbolized outdated, old-school thinking. But in playing opposite Ryan, who is one year his junior, they had to develop a new way of thinking. Father Flynn became the patriarchy, and Sister Aloysius, a woman confronted with a patriarchal system.

Photo Credit: Joan Marc

Photo Credit: Joan Marc

“I just felt that, 20 years later, with the hindsight of what happened in the Catholic Church, I needed to work extra hard to support the arguments of faith and innocence,” he explains, adding, “Because of course, 20 years later, we know that there was a big problem within the church, which the ‘Spotlight’ team exposed.” [He’s referring to the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” team, the oldest continuously operating investigative journalism unit in America, which earned a 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service after uncovering widespread child sex abuse by numerous Catholic priests in the Boston area. A 2016 film, in which Schreiber starred as Globe editor Marty Baron, and which won the 2016 Academy Award for Best Picture, also documented the team.] He warms to his theme, continuing, “Also, after spending seven years on Ray Donovan playing a guy who was a victim of a priest’s sexual abuse and then doing Spotlight, it occurred to me that it might be worth looking at the other side of that argument, that there had to be some validity to it given the millions and millions of faithful Catholics that are out there and who got lost in the mix of this massive litigious period in our history, the people who meant to do good. What happened to them in this process and to their faith? It’s a great question. John Shanley has structured this incredible play that allows us to hold some doubt around our certitude, at least in that area.”

Schreiber wanted answers, so he made his way uptown to Mount Saint Vincent’s convent in the Bronx and met with 15 predominantly unemployed nuns. Those that do have jobs mostly work in palliative care, but they are no longer running Catholic schools as they might have in the 1960s. “I was just asking them simple questions such as, “How did you become a nun?” he recalls. “And I would listen to these girls from the Bronx who were saying, ‘Well, my friend Maureen had an interview, so I went with her. I don’t know why I became a nun — I just know that I always wanted to do good with my life.’ It really struck me: where is that generation?”

In playing Father Flynn, Schreiber accrued more questions than answers. After internalizing this inherent goodness, the lack of it in today’s society struck him hard. “I immediately thought of my kids, and realized that this option of giving, of that kind of spiritual generosity — where you would want to spend your life trying to do good for others, trying to make the world a better place, trying to bring peace and happiness and love to people — is almost unthinkable in our culture today. We’ve become so self-involved in our journey, and I think that social media has contributed to that by polarizing us and tribalizing us even further for the purposes of marketing. Meeting these 80-something-year-old men and women who just wanted to do good with their lives resonated with me in a very powerful way.”

As did his discussion with Doug Hughes, the director of the inaugural Doubt production, 20 years ago. “Doug said that, for him, the parable was the Iraq War, and our certainty that we were going into that as a response to September 11. It never occurred to me when I saw the play before, but then I thought, He’s right.”

Being that Schreiber is an intelligent, inquisitive, and highly analytical man, he naturally drew his own personal parables from his research. “Mine mostly have to do with the intense polarization that I’m feeling in this country and how we are unable to pass an aid bill for the Ukraine. I believe we are on the front line of a war on democracy right now, and that there will be repercussions of ignoring the struggles and the sufferings of those people. Not because I’m Ukrainian — I’m American — but because it’s a terrible blow to democracy around the world. We’re no longer interested in progress: red and blue has become more important than red, white, and blue, and there are already tragic repercussions that will only continue to get worse if we continue in this direction. I’m worried about the environment we’re creating for our children and our children’s children.”

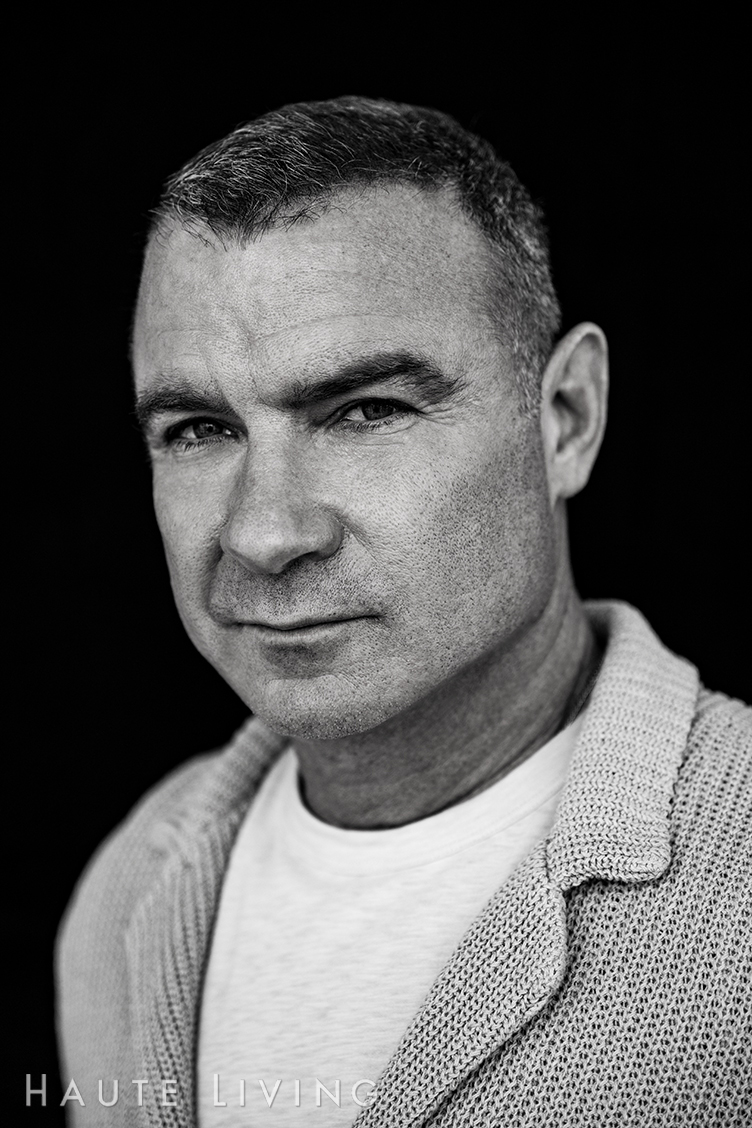

CARDIGAN: Alex Mill available at Bloomingdale’s

Photo Credit: Scott McDermott

Schreiber, whose maternal grandfather was a Jewish immigrant from the Ukraine, recently wrote an article for Time magazine that vocalized all these thoughts in a concise way. He speaks of this now, saying, “It was hard. I wanted to define and get clarity about the shared morality and values that are inherently American without going back generations, when there was a spirit of something in this country that propelled us through a couple of great wars and into a time of great prosperity. I was thinking about the value of democracy for me, and what it means to be American. It’s been a lot of things in the past couple hundred years, but what is it now? For me, it was about realizing that I have been put in a position to succeed, that my ancestors had to suffer so that I could be in this place — and that doesn’t have anything to do with Ukraine.”

It must be exhausting to carry such a terribly cumbersome weight every night for months —at the very least until the play wraps on April 21 — but it certainly seems to helps Schreiber. Yet, he is adamant that it is something he pulls out when absolutely necessary; only when it is imperative to do so will he use his pain as a weapon. “It motivates you when you need to be motivated and it makes you emotional when you need to be emotional,” he declares, before referncing a specific Hassidic quote, citing it as his favorite, which translates to this: There is nothing so whole as a broken heart.

“That’s how I feel about what’s happening in Gaza and Israel, and I think that this is an inherent part of Jewish thinking — that we live with the complexity of something before we commit to the right course of action — and I think that was in place for me before we began this play. This conflict has been front of mind for me a lot recently, the loss of life, the pain, and the suffering that those people are going through, figuring out how to move forward from that. I think that I’ve been able to harness a lot of those emotions and things in this production. Those feelings are there, they’re present for me.”

It was just as important to do this play, he says, because — much like Spotlight — it felt like a discovery, an excavation, of the truth. The heart of the play is not about a sex scandal, per se, but what we do when we’re confused, when we feel too much, and are too close to an issue to really be objective. “When we’re not sure, we commit to an idea,” he says. “We don’t investigate. We don’t live in doubt. We don’t try to figure out the truth. That, for me, is the resonance of the play right now. In exploring, becoming, and playing, it opens your mind to that possibility of having doubt, of not sticking to one idea.”

Here he cites Doubt’s opening sermon. “The last thing Father Flynn says is, ‘I know there are a bunch of people in church today who are having this crisis of faith, and I just want to say to you, doubt can be a bond as powerful and sustaining as certainty. When you are lost, you are not alone.’ And that idea — that doubt is a unifying concept and that what we share as human beings is our doubt — is so fantastic. What it says to me is that we are a community of lost, confused souls who need to rely on each other. We’ve all got issues, but the thing that binds us together is that we’re unsure — and that gives us confidence. I personally love the idea that doubt is a unifying concept. It’s a powerful tool in our society, and one that we need now perhaps more than ever.”

Photo Credit: Scott McDermott

I expect Liev Schreiber to be stern and extremely serious when I meet him over Zoom on a Thursday morning. I am pleasantly surprised when the conversation immediately turns to raccoons. Yes, you read that right.

He tells me that he’s a little wobbly because Wednesday was a two-show day, and that he hasn’t had coffee yet. It is 11 a.m. I am aghast… and impressed that he’s functioning. How can one do this?

“It’s the phone,” he moans. “The phone is ruining my life. I lie in bed on the fucking phone for four hours and I write emails. I look at stupid videos. It’s just a total waste of my life. But there it is, I’m mostly looking at animal videos, and they mostly involve raccoons.”

Admittedly, it’s surprising to me — Schreiber seems so stern and serious. But his reason for said copious raccoon viewing is extremely logical, and very much part of his personality. “When you’re trying to figure this world out, when you’re looking at the horrors of Ukraine and Gaza, when you’re dealing with kids and schedules, and all of the things one has to do when one is older than 15, sometimes it helps to look at a raccoon,” he admits.

Schreiber admittedly has a lot on his plate. There’s the show; parenting (he has children Sasha and Kai with ex-girlfriend Naomi Watts, and five-month-old daughter Hazel with wife Taylor Neisen); upcoming projects galore; his production company, Illuminated Content; his liquor label, Sláinte Irish Whiskey; and his latest effort, BlueCheck, a collective of humanitarian crisis experts, entrepreneurs, academics, and filmmakers working to help Ukrainians where and when they need it.

This is an important piece to the puzzle of Liev Schreiber in that it hits close to home; he himself is part Ukrainian. When he realized that international organizations were not able to provide rapid on-site assistance in times of crisis and were reluctant to enter war zones, he decided to do something about it and opted to help local organizations receive funding. With BlueCheck, he can provide medical care and distribution, food and relief, emergency evacuation, mental health services, shelter rehabilitation and construction, and cash assistance to internally displaced people and refugees, among other things, to those in need.

“All you ever want in life is to just feel connected and like your life’s not a waste of time; I certainly felt that way after coming off of seven years of [his hit Showtime series] Ray Donovan. I’m not dismissive of Ray, but playing such a dark character over and over again was difficult. Ray was a guy who was abused as a kid and has these pretty violent reactions to the world as a result; his is not a nice story. And playing Ray — becoming Ray — was dark for me for a long time,” he admits, adding, “Which is probably why I got involved in the Ukraine. I started BlueCheck because I wanted to feel more engaged, and I wanted this for myself, but also for my kids — I wanted them to know what it was like to care and to not be apathetic, which is something that happens to us relatively easily.”

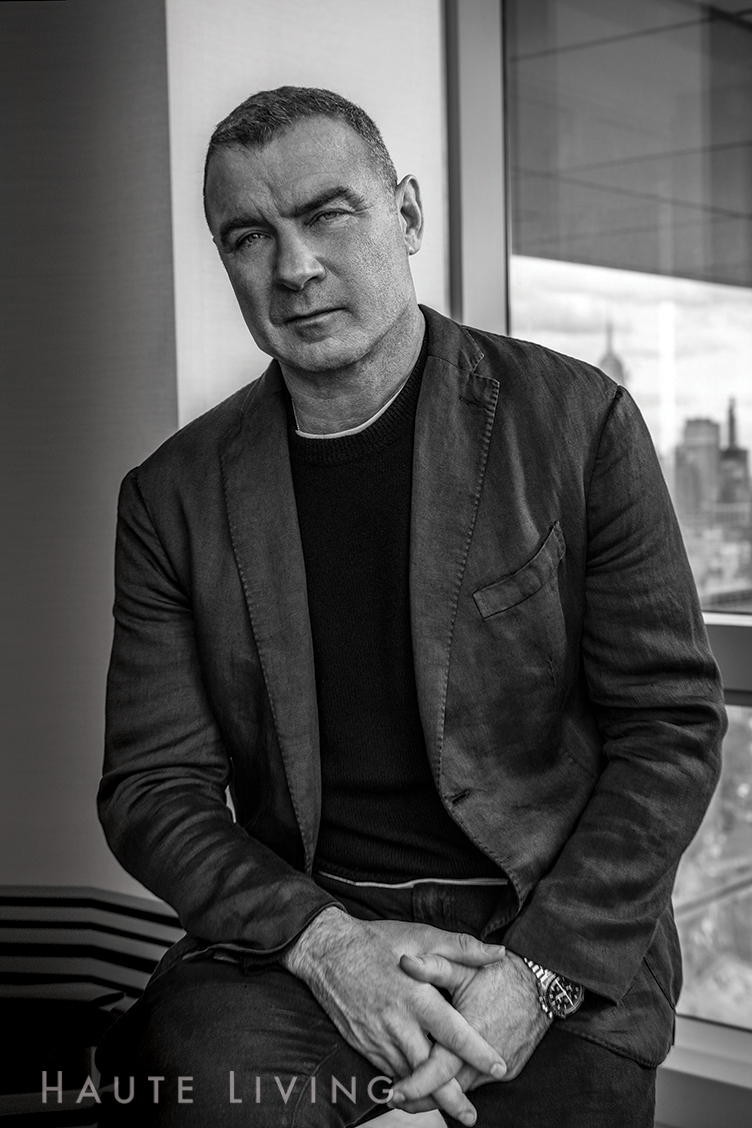

SWEATER: Rag & Bone

JACKET: Boglioli Milano

PANTS: Rag & Bone

WATCH: Omega

Photo Credit: Scott McDermott

When the war in the Ukraine first started, he recalls watching the news with his children and realized that he had never properly given them a sense of their Ukrainian heritage. “They didn’t care or know where I was from or who I was or any of those things, and pretty much, I didn’t either. I think that’s why I became an actor, honestly, to try to figure those things out.”

Maybe he didn’t give his kids a sense of their ancestry, but he certainly has always taught them to give back. Every year, they head to the Bowery Mission on Thanksgiving Day to feed the homeless. And now, they’ll have this. “For me, initially, BlueCheck Ukraine was really about that. For my kids to say, ‘Look, these people are suffering. We watched them on the news, and we couldn’t just go back to our lives without doing something about it.’”

Schreiber’s philanthropic nature even extends to things that bring him pleasure, like Sláinte. His Irish whiskey label (whose name means “good health”) began in an auspicious way. He was hosting a charity gala in Washington, D.C., which was attended by Richard Davies, who donated a $350,000 cask of 18-year-old Irish whiskey, initially aged in bourbon oak barrels, and finished in sherry casks, as an auction lot. Each $500 bottle sold benefitted BlueCheck’s relief efforts. But it was to be a one-time only thing, or so Schreiber thought.

“Richard said, ‘I want to keep doing this.’ I was thinking, I don’t want to sell liquor, but mostly it was because I’ve got enough to do; I didn’t want another job. It’s hard work and I don’t know that I’m very good at it,” he admits, though with a smile. It’s very clear that he loves this unlikely venture.

When I protest that this couldn’t possibly be true, he says, “Well, I’m not a great actor in real life. I don’t like saying, Hey, listen to me — I know about Irish whiskey. But the truth is I do know a little bit about Irish whiskey. That’s one of the few things I can say that I know, so I had to say yes. But promotion is hard; selling things really is uncomfortable, and hard for me because I’m such a cynic.” Even, as it turns out, things he believes in. “Even then, it depends on me being confident about me, which I’m not nearly as much as people think I am — that’s why I’m an actor. I’m only truly confident with characters.”

But for Sláinte, his now award-winning whiskey, he’ll do his best. Or, at least, he’ll try. “I’ve gotten over it. Well, I’m trying to get over it. I think it’s been an ongoing process for me because I really do believe in what I’m doing. I love Irish whiskey. This is the best Irish whiskey on the market right now in my opinion. It’s incredibly evocative.”

And he does love the whiskey, but what he loves most is that it has personal significance. “I didn’t grow up with my father, but I spent some really good time with him in college, and that was initiated by him coming over to my “dorm,” with a bottle of Irish whiskey. That was the most time we ever spent together talking. And so, that drink is imbued with that experience. It’s got a richness to it, and it’s got a specificity of flavor for me that is very deep and very emotional. Plus, the guy who made the blend with us, Brian Watts, was the master distiller at [Ireland’s Great Northern Distillery], and this was the last thing he ever did. That holds a lot of meaning for me, as it does being able to support the Ukraine through our brand, that we’re able to give a dollar for every bottle we sell to BlueCheck. That feels good; it feels purposeful.”

I wonder if it’s fair to say that everything he does in life is with purpose, and he cautions me not to assume so. Anything to feed his soul, definitely. Everything else? Maybe not so much. “It would not be fair to say it’s true,” he says. “I work for hire, as they say, and like to make money. I have a growing family. The older I get, the more I think I want it to matter when I work. Of course, it doesn’t always — in fact, it rarely does — but it’s nice when it does, when one of your jobs means something to people. That feels good, like the job does what it was supposed to do in the beginning, which is to connect you to people. When you’re young, you think that’s what being famous will do, make you happy, make you desired. And then you realize that’s not the case.”

Photo Credit: Sláinte Irish Whiskey

Schreiber certainly has more experience than most. In addition to his copious, Tony-winning turns on Broadway in plays like A View from the Bridge, Glengarry Glen Ross, Macbeth, and Talk Radio, his film credits include Asteroid City, Golda, The Butler, Salt, X-Men Origins: Wolverine, Defiance, The Manchurian Candidate, Taking Woodstock, Kate & Leopold, Hamlet, and the Scream trilogy. On the television side, there were his seven seasons of Ray Donovan, as well as his portrayal of Orson Welles in RKO 281, which earned him both Emmy and Golden Globe Award nominations. He also made his directorial debut in 2005 with Everything Is Illuminated.

Surely, some of these made him happy, though the character he plays in his upcoming project certainly did not. Yet, that was kind of the point: it was a test and true testament to his acting skills. Schreiber will soon star in Netflix’s new limited series The Perfect Couple, based on Elin Hilderbrand’s New York Times best-selling novel of the same name opposite Nicole Kidman later this year. The project revolves around the secrets that are spilled when a young bride’s maid of honor turns up dead during the morning of her Nantucket wedding to a wealthy heir.

“It was bizarre,” he declares of filming the series. “I play a character that I would never, ever have really wanted to play. But this is the thing: actors — for the most part — must find a way to not only like the person they’re playing but to love them. That may not be true for everybody but that’s what I believe. They are more than family — they are you — and so, unless you’re suicidal, you’ve got to figure out how to connect with them. This was probably one of the hardest exercises for me in that I honestly didn’t like [my character, Tag Winbury, the groom’s father]; he was one of the worst people I’d ever read. I didn’t want to do it (but the director, Susanne Bier) just said, ‘You have to jump, you have to just leap off of it and do it.’ I said No, I don’t want to do it and I don’t have to do anything, but I did decide to jump with her, and with Nicole. It was a leap of faith. And it’s good to do something where you’re thinking, It might not work out; this might not be good. In fact, I’m pretty sure it’s not. And someone says, ‘Go anyway, take a risk’ and you do… and there’s something about that that feels good.”

Schreiber says that feeling good was a major part of the reason he signed on for Doubt, as well. “I didn’t have a great experience on the last play I did [2016’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses]. It came right at a really hard time in my life. I had just gotten separated. I was living alone with my kids in the Financial District, and I wanted to be close to Nay [his ex-partner, Naomi Watts]. I was doing a play that I couldn’t relate to, about sexual carnivores. It was not a good time in my life, and I was just really lost. I think the choice to do a play again was partially about that; partially about getting back on the horse and just doing it again. Not worrying about it: like, If you suck, you suck.”

He shakes his head. “So much of my own personal journey has been getting over that attachment to not sucking, not being bad at something. Which is funny, because the whole principle of acting is that to be good at it, you have to be willing to make a fool of yourself. You have to be willing to be a jackass. You forget that sometimes, because when you do something for a while, people think you’re good or attractive — something you want to be in real life — but it was just a character that you created. I think that’s the problem with fame; you start to believe your own press. A real career in the arts is about trying to figure out identity. My consistent hang up has been this thing about not wanting to suck, about trying to be smart and to elevated, so it was an exciting thing to do the play because it felt like a risk, just like The Perfect Couple did.”

Schreiber, though he may refer to himself as a work-for-hire, blatantly is not. He has choice, and the ability to take risks. He has the freedom to spend 20 minutes doing his favorite thing, noodling on the piano, even if he can’t do precisely as he wishes and sits there for three hours, looking up random Stevie Wonder songs on the internet and attempting to learn them. He also has freedom itself —and that is not lost on him.

“I’m just so desperate for everyone to recognize the value of it and the existence of it in their own lives. What happens if we lose it, when freedom starts to get wheeled away, when those liberties start to get taken away from us?”

Yet, recognizing and appreciating what he has hasn’t always been easy for him, either. “Reminding myself how lucky I am to have the freedom that I do is something that I’ve always personally struggled with. My whole life, people have spoken about gratitude. I still struggle with it, that feeling, that happiness that comes from being grateful. Maybe I’m doing it wrong.”

I doubt it, but as he himself said, one should always have doubt. And if that doesn’t work, well, there’s always raccoon videos.

CARDIGAN: Alex Mill available at Bloomingdale’s

Photo Credit: Scott McDermott