Michael Keaton Pursues the American Dream in ‘The Founder’

Michael Keaton doesn’t like playing a bad guy. Come on, he was the original (and, debatedly, the most iconic) Batman, for Pete’s sake! But like the Academy Award-nominated actor that he is, when he commits to a part, he goes all in. Plus, sometimes, isn’t it good to be bad?

If he hadn’t earned his villain stripes playing sociopath Peter McCabe in the 1998 thriller, Desperate Measures, Keaton definitely earns them now. In The Weinstein Company’s upcoming drama, The Founder, he plays a man who refuses to settle, at whatever cost. Keaton shares the biographical tale of Ray Kroc, who morphed from a down-on-his-luck milkshake dispenser salesman to the man responsible for making McDonald’s into one of the most powerful franchises in history. The story—as told by director John Lee Hancock and screenwriter Robert Siegel—revolves around the man who hit pay dirt in his discovery of the first McDonald’s, a progressive yet family-friendly burger joint right here in Southern California. He convinces the brothers McDonald (yes, they actually existed) to hire him as a franchising agent. In 1961, at the age of 58, just seven years after said dream was born, Kroc bought out the chain for $2.7 million. It is now responsible for feeding one percent of the world’s population daily.

Onscreen, Kroc won’t win many admirers. What he does have, however, is a champion in Keaton. “I think there’s a fair amount to admire about Ray Kroc,” he says. “His work ethic is so strong, and he was so persistent that he succeeded. The truth is, the McDonald brothers didn’t see what he saw, what [the outcome of ] what they started could be. Ray saw it as it ended up becoming: a cultural shift.”

Semi-spoiler alert: at the end of The Founder, which is expected to be released by year’s end, Kroc stands in his swanky Beverly Hills mansion with his beautiful, young new wife (played by Linda Cardellini). She is, physically, an upgrade from the quiet, humble and long-suffering woman who stood faithfully by his side for almost 40 years, a role beautifully acted by Laura Dern, of whom Keaton raves “could play a monster and somehow you would feel for her; she just drips with empathy.” He is rich, he is successful, he has it all—or does he? As he stares at himself in the mirror, the audience can see a glimmer in his eye that suggests otherwise.

“There really wasn’t a cost [for Ray],” Keaton muses. “There comes a point where he kind of makes a deal with the devil. What I don’t subscribe to is that it almost got sadistic—and ‘maybe’ is not a word you need in that sentence—because he just keeps turning the screw and turning the screw and turning the screw.”

The takeaway from The Founder is that Kroc, who died of heart failure at the age of 81, is the ultimate capitalist. It paints a picture of a ruthless man who would do anything to achieve his goals, yet it also suggests that he might have had regret for the things he did in his quest for wealth and power.

Hancock toys with the idea of remorse, choosing a few shots that Keaton compares to the 2014 Best Picture-winning film by Alejandro González Iñárritu that earned him his first ever Academy Award Best Actor nomination. “I love how Birdman ended, because [the ending] is still out there. Nothing was wrapped up neatly, and I don’t think, in this film, it does either. You see a very, very subtle flash of Ray wondering, ‘Did this work out the best way?’ You could look at it and go, ‘Yeah, he’s really happy with how things worked out.’ But to not regret anything would be robotic, inhuman. Who knows what’s really going on in Ray’s mind, or his heart?”

However, to play Kroc any differently, to make the audience sympathize with him, would have been a disservice to the film. “The one thing I didn’t want to do was back off. I never agreed with that emotion of ‘He’s awful, but really, don’t you kind of like him?’ I don’t buy into that. If you play the role of the bad guy, as I have from time to time—Desperate Measures or whatever—you commit to that. You don’t back off. I’m not a fan of any sort of acting where you have to be liked at the end of the day. I just don’t subscribe to that.”

What Keaton does subscribe to: the notion that, with hard work, you really can achieve everything. He himself is a perfect example. “I work really hard, and I’m basically in that self-made category, to speak broadly… and I’m proud of it. That’s not to say there’s been a shortage of people along the [way] who at least gave me the opportunity, that’s for sure. I don’t think anybody can do much in any field where you don’t at least get an opportunity.”

“PERSISTENCE IS THE KEY TO SUCCESS”

In The Founder, Ray Kroc utters this inspirational line. The same could be said for Keaton, who, like most Hollywood stars, has weathered his career lows along with its highs. Thanks to the recent successes of back-to-back Best Picture Oscar winners Birdman—a film that resulted in his first Best Actor Academy Award nomination for his turn as a faded American actor, coincidentally best known for playing a superhero—and Spotlight, as Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Walter Robinson, the 64-year-old actor is firmly back on top. Dare we say it: he might even be going for Oscar gold three years in a row thanks to The Founder.

It’s true that he now has his pick of plumb projects, including an upcoming turn as a super villain (now familiar territory) in Marvel’s Spiderman: Homecoming, and as a Cold War veteran in the big screen adaptation of Vince Flynn’s bestselling series, American Assassin.

While he refers to the former as a “big budget movie that will be an awful lot of fun,” the latter seems to have hit a few snags. Still, Keaton is confident that the end result is going to be awesome. “American Assassin needed a reshape. Not that it was bad, but the tone of the movie needed to change. The director [Michael Cuesta] is doing that with the writer [Stephen Schiff ] with a bunch of notes from me. I hadn’t actually done that before, but I didn’t want to do it as it was written. By the way, this wasn’t just me, it was everyone involved: we didn’t think it was there yet.”

His character, Stan Hurley, is a mentor to the young assassin, played by The Maze Runner star Dylan O’Brien. Although this type of character was new for him, Keaton was up to the challenge for one very significant reason: “I’m going to be really honest—this [movie] has potential for international appeal. I run a business in a sense, and you have to go international as long as you can, because that’s what keeps the movie business going.”

If American Assassin becomes as successful as Keaton believes it will be, he’ll finally be able to focus on his passion projects—including Buttercup, a small-budget film he had planned on directing until it hit a stone wall when he ran into casting problems. “I couldn’t find the right guy,” he admits. “I had gone to Jack Nicholson [his former Batman foil] and had a long conversation with him, and I talked to Clint [Eastwood] and he had almost done the exact same guy in Curveball. I was hoping he’d say he’d play it again.”

One role fans would like to see Keaton reprise is Beetlejuice, the mischievous, devious ‘bio-exorcist’ he played in Tim Burton’s 1988 film of the same name. Last year, it looked like a sequel was well on its way to the big screen when star Winona Ryder prematurely announced the project on Late Night with Seth Meyers (Burton’s rep has since said the sequel rumors were fabricated). All of this is news to Keaton, who had never been approached by anyone about it. “I hear this all the time. People know more than I do, and they come up to me all the time and go, ‘So Beetlejuice is happening’ and I have no idea.” He genuinely asks, “So is the latest that it’s not happening?”

There’s also no chance he’ll return as the caped crusader, a role that has seen many Hollywood hunks—such as George Clooney, Christian Bale and, most recently, Ben Affleck—fill the role since he officially ceded his mask and codpiece in 1992. Since then, Keaton hasn’t been keeping up with the Jones’— or the Afflecks, either. It’s nothing personal, though. “I’ve seen bits and pieces of them. It’s not that I don’t like them, I just never got around to it. Christian Bale is such an amazing actor and [that director Christopher Nolan] is so great that they must have at least been pretty good, but I have no idea.”

Burton is responsible for Keaton’s two caped crusader films—Batman and Batman Begins—but, when the director left, so did his star. “I was all into it if Tim was going to stick around, and if they would have gone down the road I preferred,” he says, noting, “Chris Nolan ended up doing basically what I said I would prefer if there was a third movie. [The powers-that-be] didn’t hear it: they were going for bigger, more color. I just didn’t get it at all. If Tim had pitched me that idea [I might have considered it]. My overall sense, what I hear from what people tell me, is that for some reason [none of the following films] ever got Batman’s charm. He’s a quirky dude. He’s screwed up. He’s odd.”

This is not how Keaton would describe himself. If you push him, he’ll tell you that it depends on the day, but mostly he’s “fortunate” and “lives a varied life.” Both statements are true. Though he clearly has a place in the Hollywood machine (and a home in Pacific Palisades), he prefers to spend time at his ranch near Big Timber, Montana, where he fly-fishes, hikes, plays tennis, walks his dogs and rides horses. He is a man in constant motion, shifting imperceptibly, but often. He claims he doesn’t know how to be indoors for too long, and we believe him.

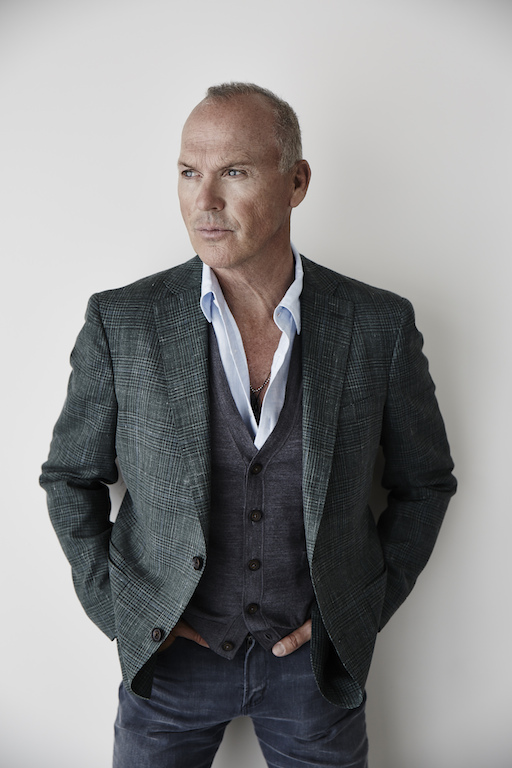

On this unusually grey day in Pacific Palisades, Keaton (born Michael Douglas, strangely enough), is the one bright spot in an otherwise dark room. His expressive, ocean-colored eyes become brighter as he gets more animated. He has the energy of a dozen men, easily moving from topic to topic, sometimes shifting conversations upon themselves like Jenga pieces. He has already read his customary two newspapers, taken a meeting, completed a fashion shoot and still found time to discuss the current political climate.

Because we’ve topic-hopped and landed on exercise, he confides that one thing he truly misses is playing team sports; softball and basketball are his top choices. “I was always in a league somewhere, and I really miss that—I miss it a lot,” he says. “I miss the whole notion of teams. I never liked the idea of clubs though. Clubs are exclusionary, like you’re not good enough or cool enough.”

Which, in his opinion, is a good way of describing Hollywood itself. “I think it was Steve Martin who coined the phrase, ‘It’s like high school, with money.’ You know, [Hollywood] is clubby: who’s cool, who’s pretty, who’s too fat, who’s the groovy guy… it’s so fucking stupid. I never really dug that [aspect of the business], but I love teams, and filmmaking is a real team sport.”

Unless you’re benched, that is. “I went stretches where I didn’t work, and most of that was my choice, but also, sometimes, [it was] because nobody was making any offers. That’s a problem that I’m going to change. I’m also more in the mood, more interested in work than I have been in a long time,” he says.

Keaton isn’t sure what prompted this renewed career vigor, but he’s going to continue riding the wave and see where that crest takes him. “I think that happens to people,” he muses. “It’s a good thing I didn’t quit because [everything] comes around again. I’ve heard this happen to people—not just in show business—[where] all of a sudden, you get interested in work.” He adds, “I like that my opportunities are there now that weren’t there before. I’ve always had offers, but there were certain periods where the offers weren’t necessarily great, or some were really good but I was picky and choosy about them. Most of the time, I made decent choices. I look back at certain films [though] and I have no idea. [If someone said] ‘Tell me why you did that movie or I’ll pull the trigger,’ I would say ‘Pull the trigger, because I have no idea.’”

But don’t get him wrong—as disappointed as he may have been in some of his choices, he never truly let it get the better of him. “I never caved in to desperation,” he says. “Desperation will kill you. There were certainly periods where I would get frustrated or confused, though. I mean, I’m a human being.”

There was a brief moment when he thought he might retire completely from the industry—perhaps live permanently on his Montana ranch—but it was short-lived. “I sat out for periods of time. There were periods when I wasn’t getting the offers that made me go ‘Ooh, I really want to go do that.’ And I have taken a couple of movies to just grab the dough and throw it in the bank so I could sit back even longer until I got the kind of things I really wanted to do. So, not retire exactly; I was not interested in myself. I would hear my voice in movies as I was doing scenes and go, ‘I’m so uninterested in what I’m doing right now.’ I didn’t think I was very good. I wasn’t down on myself, but I was right on the verge of starting to repeat myself, and I wasn’t enjoying it.”

Since he’s “100 percent a ‘cake and eat it too’ guy,” Keaton wanted it all: the career, normalcy, and to be a good dad to his son Sean Maxwell, who is now 33 and a successful songwriter and producer. “I wanted to have a really nice life… a normal life,” he says. “I wanted to be around to help raise my kid—his mom [Caroline McWilliams, whom Keaton divorced in 1990] raised him exquisitely, as well—but I wanted to do that for me. I was selfish, and I wanted to have that and I wanted to have the jobs I wanted, and I wanted to have enough money. It’s hard to get all that. You seldom get it all at one time: you get a little bit here and a little bit there. I definitely always wanted to get both if I could and, for the most part, I’ve gotten it. What I don’t have is a whole ton of craziness around my life. There are moments of it, but I’m fortunate that I get to have a normal life, a fun life, and make enough dough to get to do what I want to do.”

He continues, “In a large sense, I’ve gotten [what I hoped for] and I’m still getting it. In other ways, I’ve barely scratched the surface… but it comes with certain costs. Some are bad, some aren’t that bad, and that’s the way it goes.”

Keaton speaks with a depth of honesty, a frankness, that is rare for such an iconic star. He is open and honest as he discusses the past and how it has impacted his present. Yes, he made sacrifices along the way—including passing on certain films, or adjusting his schedule to accommodate his son—but he regrets nothing. “[I had] little costs here and there. I was really an attentive father because I think that’s your job. I don’t deserve any credit for it; it’s what you’re supposed to do.”

There is a fine line to the cost of success, and Keaton refuses to walk it. “I believe in keeping your nose to the grindstone, bearing down, keeping your eye on the ball—and, if you want something, you’ve got to be emotionally tough, you’ve got to be spiritually tough, you’ve got to be sometimes physically tough to say, ‘No, I’m going to get what I want. I know there’s more for me here,’” he says. “There’s almost no way to get at that without giving some things up and, in my case, I don’t really feel like I gave up anything. I’m blessed. I don’t think there’s a successful person out there that hasn’t [dealt] with some cost somewhere.”

At the end of the day, there’s a little bit of Ray Kroc in Michael Keaton. He is a man who believes, as he says in the film, that “persistence is the key to success.” Cost, sacrifice, hard work and love have brought him to who and where he is today. He is a happy, fortunate, successful man—a true American dreamer. “I get worried if I feel myself not dreaming a little bit,” he says. “You never want to stop having ideas, or thinking about the ‘what if.’ I really don’t think in terms of my career all that much. I just always wanted to be good at what I did; it’s really that simple. I wanted to be really, really good and keep getting better.”

McMission accomplished.