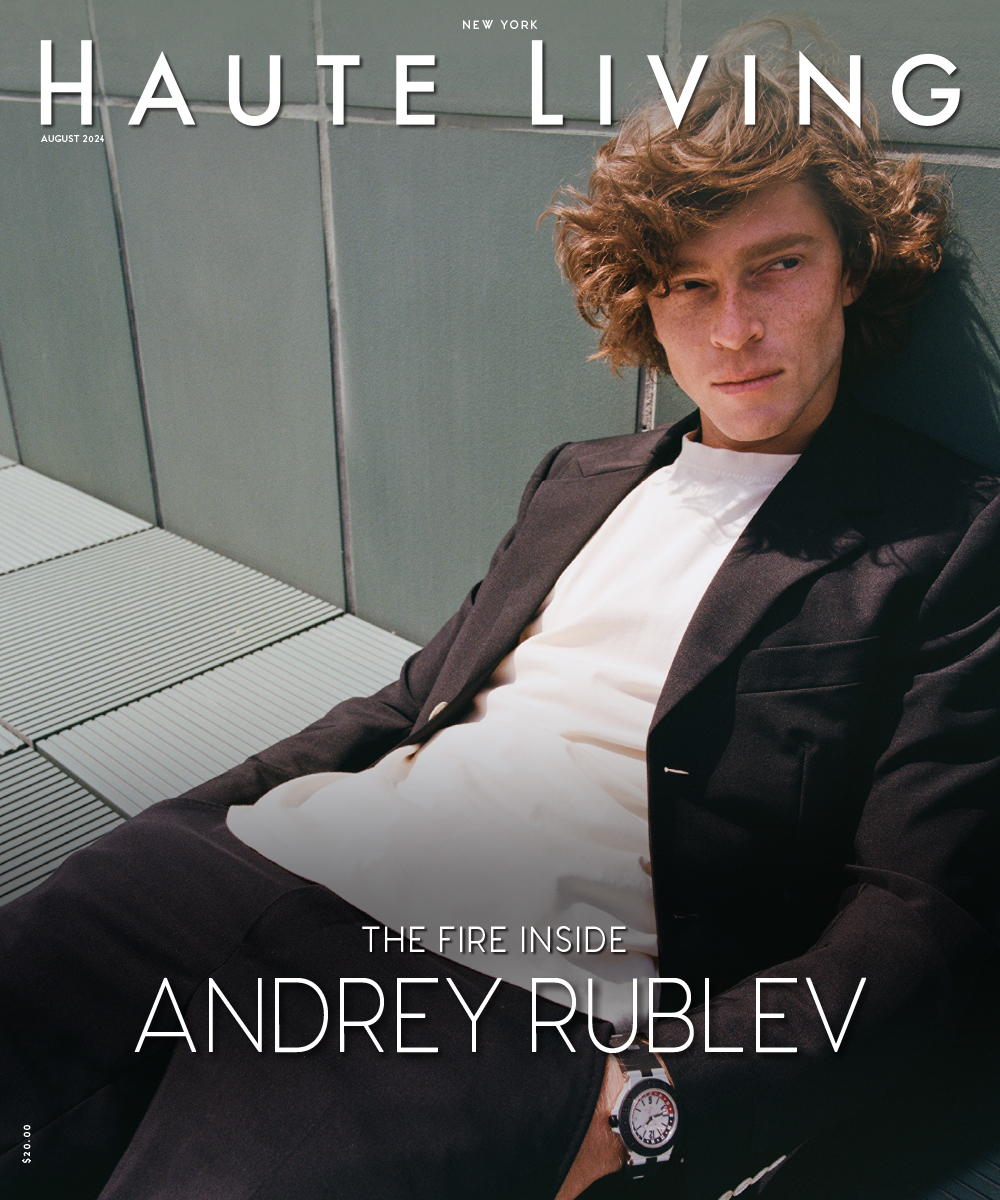

ATP Pro Andrey Rublev Talks Tennis, Time, And Controlling His Temper

T-SHIRT: Andrey Rublev Brand

WATCH: Bvlgari

Andrey Andreyevich Rublev didn’t sleep with teddy bears as a child; instead, he slept with tennis rackets. Which means, naturally, that he was truly always destined to play tennis professionally.

The 26-year-old Russian, ranked No. 9 in the world at press time, shares this from Halle, Germany, in June, where he’s about to compete in the ATP 500 Terra Wortmann Open. “I did sleep with tennis rackets when I was little,” he admits.

Tennis rackets plural. Meaning, there was not just one childhood favorite that offered him toy-like comfort, but a slew. “My mom would buy a new model every time one arrived, and I was so in love with it. I couldn’t wait to play with it, so I slept with it,” he confides, before admitting, “But then, the next day, I’d have destroyed the racket already.”

Does he still feel so passionate about the game that he gets into bed with the tools of his trade? Well, no, “but sometimes I do still destroy the rackets,” he says sheepishly. [The most recent evidence of this was at Wimbledon, when he did not destroy a racket, per se, but hit himself with one.]

Clearly, Rublev is not a good loser, but then, what competitor truly is? At least he’s actively aware of his faults and is trying his best to change them… even if he doesn’t always succeed.

And so, whether he’s sleeping with them, throwing them, or playing with them, at least his love of the game (rackets included) remains consistent — as does his need to win.

“When I was a kid, I was super competitive,” Rublev confides. “I wanted to win everything. Most of all, I was competitive with myself. For example, I could say to myself, I need to make 10 basketball shots inside the goals, and I won’t stop until I make 10 shots in a row. I will keep doing this until I make it. My parents would go crazy, telling me it was time to go home. I would always be super pissed and tell them that I wasn’t going home until I [hit my goal].”

Now, things have changed — in some ways, that is. “Outside of tennis, I’m super relaxed. I’m not competing in anything but tennis,” he swears, noting, “It makes no sense to compete in stupid things. Even if you’re just playing video games or competing with your friends, it’s not an honest relationship, not a real friendship. When I was a teenager, I started to see a lot of this, to realize that competition meant jealousy, and I didn’t want to be like this. For me, tennis is more than enough.”

He fully channels the competitive drive he used to have for silly things on the court these days (and just off it, post-match, as it were). There is not one player he enjoys besting more than another — it’s about the competition itself, you see, and being the best he can be. “Any tournament I play, any player I’m up against, I want to win. It’s the same feeling for every player, and the same for any tournament. Whether I’m playing an ATP 250, a Grand Slam, or a Master 1000, I could go crazy if I’m losing matches. In tennis, it doesn’t matter the tournament. Even if it’s an ATP 250 and I’m not losing anything — not points or positions — I’m still getting mad at myself if I lose.”

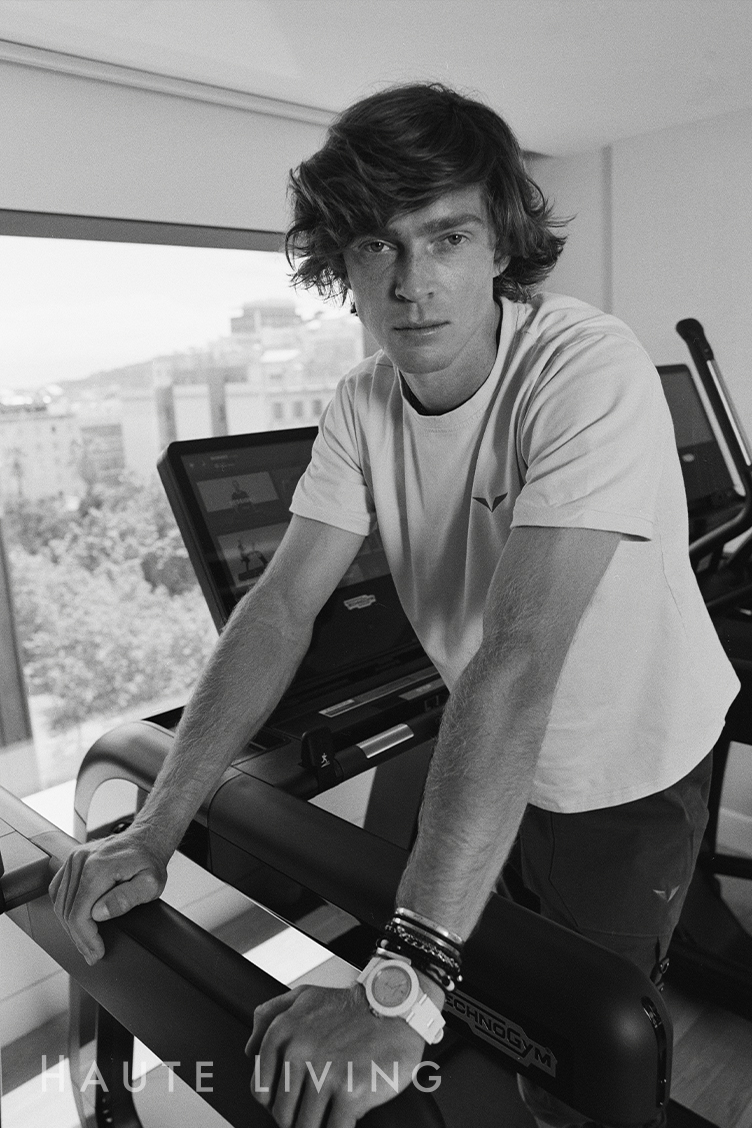

T-SHIRT: Andrey Rublev Brand

WATCH: Bvlgari

This is because tennis isn’t just Rublev’s profession, it’s his passion. The sport gives him everything he needs, he says, and always has — despite the frustrations of occasionally losing. Growing up in Moscow, Russia, it didn’t hurt that his mother, Marina Marenko, was a tennis coach who also worked with players such as Anna Arina Marenko, his older half-sister (she also coached Rublev himself in his youth), or that his maternal grandfather, Andrey Fyodorovich Tyurakov, was also an amateur tennis player whose doubles partner was Boris Sobkin, a coach of professional tennis player Mikhail Youzhny. His grandfather taught him to play various different sports, including football, basketball, volleyball, and even ice skating. Both were greatly supportive when he eventually decided to commit to tennis full-time.

It also didn’t hurt that he became extremely good very early in his career. Rublev began winning local tournaments at age six, and playing in international tournaments at age 10. By age 15, he had won one of the top junior competitions, the Orange Bowl, in Florida. Less than two years later, he became world No. 1 ITF Junior player after winning the 2014 Junior French Open. He also took home the bronze medal in singles and the silver medal in doubles at the 2014 summer youth Olympics in Nanjing.

In 2014, he turned pro, making his major debut at the 2015 US Open as a qualifier, winning his first ATP title that same year at the 2015 Kremlin Cup in doubles, with Dmitry Tursunov as a partner. Later, he was named the ATP Most Improved Player of the year in 2020 after jumping from No. 23 to 8 in the Pepperstone ATP Rankings. He achieved his personal best career ranking of No. 5 in 2021 at the BNP Paribas Open in Indian Wells, California. Throughout his professional career, he has won 16 ATP Tour singles titles, including two Masters 1000 at the 2023 Monte-Carlo Masters and at the 2024 Madrid Open. He also won the gold medal in mixed doubles at the 2020 Summer Olympics alongside Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova. [Though, like most professional athletes, he has had his fair share of upsets, and injuries, too: he missed three months of play in 2018 due to a lower back stress fracture, and six weeks in 2019 because of a right wrist injury.]

But again, this is his passion. I’m reminded of Ted Lasso’s Dani Rojas saying, “Football is life!” when I speak to Rublev, because for him, this is 100 percent true of tennis. “Off the court, this is who I am,” he confesses. “I’m practicing all the time, every day. I actually really enjoy it.”

I mostly believe him. The man spends the majority of his life either working out or playing tennis, with time for little else in between. [That said, he’s an interesting guy, whose hobbies include making his own electronic music for fun, wakeboarding, snowboarding, fashion, and playing chess.] But the nature of his physicality changes on a daily basis as he assesses whether he’s pushing himself too hard, or, conversely, if he’s being too soft (which is rare). “I want to give 100 percent every day, but you can’t have 100 percent intensity 100 percent of the time, or you’ll burn out after two or three days,” he notes.

His days typically start with a two-hour workout at 10 a.m., followed by two hours of tennis practice at minimum, and then another workout or another two-hour practice session later in the afternoon, six days a week. His on-court performance is the most important thing and, naturally, he wants to be in prime shape and fully prepared for the matches at hand — a rigorous schedule of two-to-three tournaments per month in various cities worldwide.

“We don’t really have one full week between the tournaments, but even with that [small amount of time off], I try to use it as much as I can to build something in my game or at least to improve my game,” he shares, noting, “But I cannot push myself too hard because I still have tournaments, and I’m on the court 80 or 90 percent of the time.”

As a player, Rublev is known for his ferocity on the court as well as his style of play: he’s an offensive baseliner with a favored shot of a big forehand as well as a lethal two-handed backhand. He also has a powerful first serve that often reaches 125+ mph. And though that sounds incredible to me, the way he sees it, there are other athletes with similar styles to his. What sets him apart, he feels, is his stamina. “Since I was a kid, I’ve had good endurance — I could play for a really long time — and I had a lot of aggressivity in my game, but I was quite slow. I was not really a fast guy, so I was compensating for those things by being able to hit harder.”

It’s not like Rublev can push himself to be a player — or a person, for that matter — that he’s not. There’s nothing that helps his game more than putting in the good, old-fashioned work. A reward system is not his style.

“I’m really lucky that I don’t need to do anything to motivate myself [to play better],” he says. “I truly enjoy practicing and putting in the work. I don’t need [positive reinforcements]; it comes naturally because I enjoy the process. I am and always have been motivated anyway.”

T-SHIRT: Andrey Rublev Brand

WATCH: Bvlgari

ANDREY RUBLEV HAS ALMOST NO FREE TIME THESE DAYS, but when he does, he’s spending it one of a few ways: working on his Andrey Rublev Foundation; shaping his sartorial efforts, inclusive of his clothing line, Rublo, and his ambassadorship with luxury brand Bvlgari; and, most importantly perhaps, working on himself.

Although he’s just 26, Rublev says there have been goals he’s been working towards for a long time — both of which launched within the last year. Rublo came first, in December of 2023. Its inaugural collection, “Play for the Kids,” featured a range of casualwear and tennis apparel.

Previously, he had not been able to launch a clothing brand with this type of casual and match apparel as he had been a Nike athlete, and wore said brand exclusively on-court; it would have been a conflict of interest to do so. Now is a different story: he can play in Rublo. “I realized that maybe now was the moment [to launch my line], because while I’m still playing tennis, I can promote it by wearing the clothes. I also didn’t want to feel regret about not [realizing] my dream. [Also] at the time, I hadn’t launched my foundation yet, and I wanted to do something that had more meaning.”

When profits from the Play for the Kids collection reached $150,000, he announced the creation of the Andrey Rublev Foundation, sharing that said funds would be made available for his nonprofit to distribute; he had not previously disclosed where said proceeds would be allocated.And so, in March of this year, the foundation, which aims to provide essential resources and supports children around the world who are struggling with critical medical challenges, was born.

For Rublev, this was a personal endeavor, given that he deeply believes in the transformative power of support in shaping the futures of children, though giving back in general was always paramount to him. “It was something that I wanted to do a long time ago, but I was still too young, and I didn’t have any idea how to do it. But I always had this idea in my head [which began] when I started to travel the world and saw so many families suffering. It started to get to me, because I had everything I wanted. And I knew that, in the future, I would need to do something. I wanted to give more than I receive.”

Right now, this is being done on a smaller scale, which he confidently feels will significantly increase as time goes on. For the moment though, he’s mainly trying to raise money from clothing sales in support of the charity. There are other initiatives in play, but reasonably, he prefers not to speak about them until they’ve actually been executed. But this is only the beginning; there’s time.

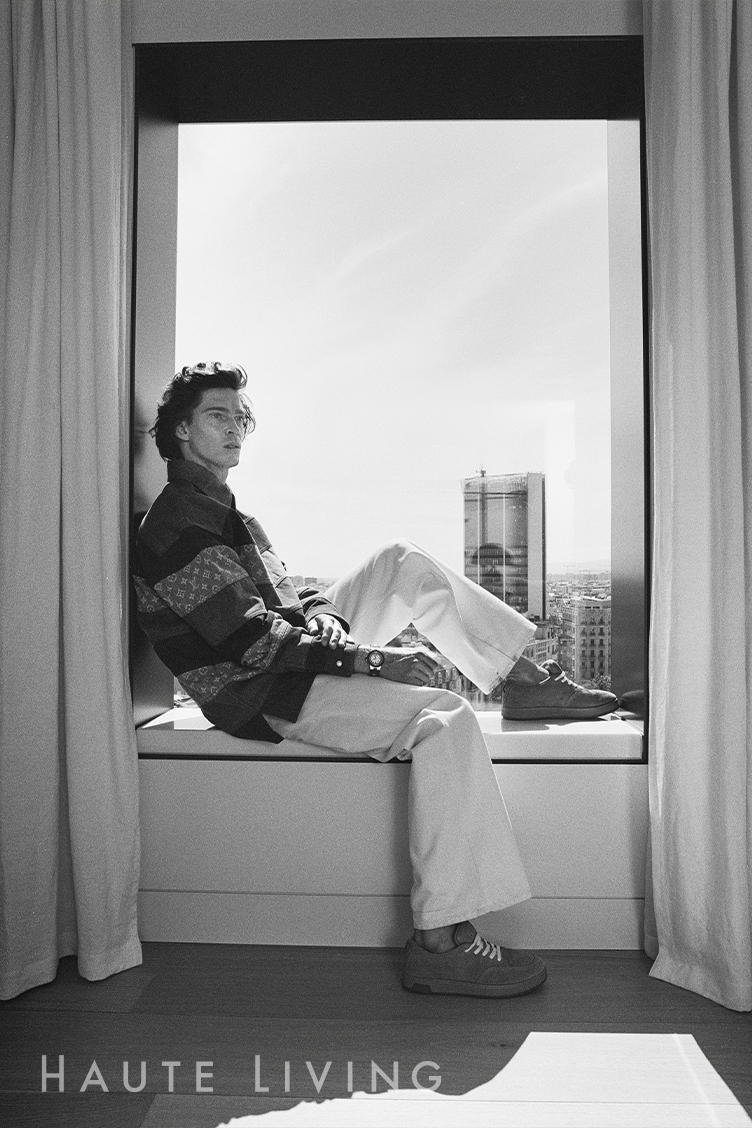

TROUSERS: Isabel Marant

WATCH: Bvlgari

Speaking of time, well, when we get onto the topic after he professes his love for the Bvlgari Skeleton watch and its thin, black straps, he shares that, to him, the passing of time means “stress. Time is always running out. There never seems to be enough time — especially when it comes to finding the balance within myself.”

Rublev says that this is something he’s actively trying to do — especially in light of his recent displays of on-court temper. “For the moment, I’m trying to stay calmer. I’m trying to do different things to be in the moment and to enjoy the moment. I’m trying to think less and stay more grounded in the present instead of thinking about the past or the future.” He pauses, and laughs, “At the moment, this is not working for me, so I don’t know what to do.”

Meditation hasn’t helped, though he continues to try it. The determination he uses to play has not prevented his temper from flaring, so at the moment, Rublev is at a loss. Still, he’s trying — and that’s the important thing to note.

“On the court, it’s very funny because of course, when I’m starting to get stressed, I’m talking to myself, and I’m saying, OK, stay calm, stay quiet. It’s OK, it’s normal. And sometimes, this works. But most of the time, even though I have these [calm thoughts], on the outside, I’m destroying everything. I start to scream, I destroy rackets, I complain. But I still have this voice inside my head saying, come on, be calm. You need to stay calm. But outside, you can see that I’m not calm at all.”

That angel on his shoulder, that one calming voice, is his saving grace, and he knows it. “I’m never getting mad [at that voice], because it’s the only one inside of me that’s a good person. When I’m doing these things, I’m grateful to have that voice telling me to calm down, focus, and that everyone is having bad days and losing matches. That voice is the only hope I have,” he admits.

I tell him not to be so hard on himself, but he’s adamant that he needs to do better. “I am getting mad at myself,” he confesses. “When I get off the court, if I’ve behaved really badly, I feel guilty about it. I feel disappointed in myself. And it does take time to calm these feelings down, sometimes even a couple of days.”

When Rublev isn’t competing, he’s the most chilled guy you’ll ever meet — he swears it. “Off the court, I’m a very open and relaxed person. Even after the matches, it’s easy to talk to me, easy to explain things to me, because I’m listening; I’m accepting all the mistakes that I’ve made. I’m open to listening to critics. I’m not getting mad [when people say negative things about me] because they are right, and I understand this — and that’s why I feel disappointed with myself that I’m doing those things. Off the court, I see the big picture, where many times, when I’m on the court in the midst of it, I can’t see past [my frustration], and so I behave like this. But then, after the match, pretty much right away, what I did and what I have done come to me fast and I start to see the big picture.”

What Rublev truly plans on working on with persistence is his patience — or lack of it. “I want everything fast, and then, when I start to get more stressed, when I start to get more pissed, I start to behave [poorly] or disrespectfully to the people who are around me. On-court, I still need to learn to be the way I am off the court,” he maintains.

He is a work in progress, of that Rublev is certain, but he’s trying to improve his temper, and always in pursuit of being the best player he can possibly be. And as much as time is fleeting, it’s how one uses it that makes the most impact, and he, at least, appears to be using his time wisely.

That said, the concept of time itself is one that seems to bring him apprehension. “Time is very short, and it’s passing very fast. I don’t think that there is even enough time to become a better version of yourself,” Rublev confides. “I mean, I’m trying to be a better version of myself as much as I possibly can while I have this time, but I feel that when this moment arrives, not much time will be left. We cannot control those things.”

True story. But if he’s lucky — and I personally feel that he will be — Rublev can definitely learn to control his temper. And that, for a champion, seems to be a truly achievable win. It, like everything else in his professional life, just takes a little practice.

T- SHIRT AND SHOES: Loro Piana

WATCH: Bvlgari