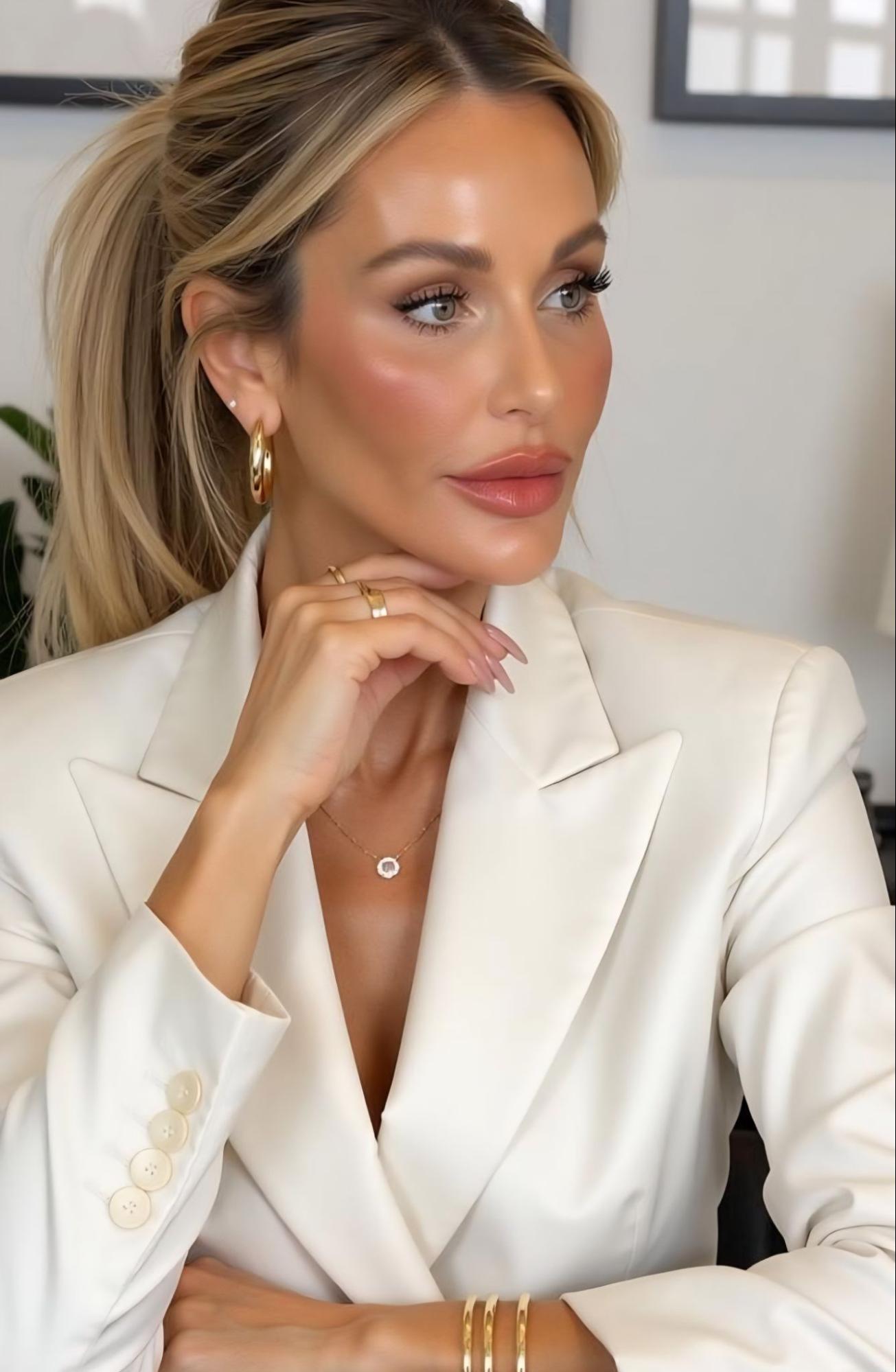

Woman of Substance Sheila Rosenblum and Her Race to the Top

Photography: Weston Wells, Hair: Trennace Gallatin, Make Up: Natasha Smee

When Sheila Rosenblum went looking for a new challenge, she found it—and then some—in the fast-paced world of thoroughbred racing.

While she always loved horses—and, like many socially prominent women, was drawn to the equestrian world—it was the prospect of an empty nest in the not too distant future (her daughter, Kara, and son, Erik, would soon be teenagers) that also served as motivation to move beyond a gilded Park Avenue life and photo ops on Manhattan’s charity circuit and into a sport where few women have thrived.

“I’ve long been fascinated by horses and dreamed of owning one since I was young,” Rosenblum says. Back then, she could only fantasize about a canter through Central Park; as a youngster, ballet was her consuming passion; and as an up-and-comer both at the School of American Ballet and The Royal Ballet School, riding just wasn’t an option. “It’s a dangerous sport and dancers can’t take the risk,” she says.

Rosenblum left ballet at 19 after the Ford and then Wilhelmina modeling agencies came calling. While she was freed from hours of rigorous dance practice every day and could enjoy a more flexible lifestyle, broken limbs on fashion models are about as welcome as they are on ballerinas— arm slings and plaster casts hardly make for a good photo shoot. When she began to phase out of her second career, she took up dressage, often described as horse ballet. It was a most appropriate sport for a former dancer to choose.

But it was only in 2010 that Rosenblum’s passion for horses put her in the path of a life-changing opportunity. While on safari in Africa she learned about a “fantastic German filly” that was for sale. And then it all began to click: Here was the chance not only to fulfill that desire to own a horse, but also to start an entirely new career—racing thoroughbreds. Once Rosenblum owned the horse, she quickly became consumed with her new venture.

Just as quickly, she learned that enthusiasm alone wouldn’t take her very far in a complex, old-school sport with daunting oddsforsuccess.“I had horrendous beginner’s luck,”sherecalls.“If there was something that could go wrong, it certainly did.”

Rosbenlum’s first filly wasn’t a winner, not by a long stretch. Then she experienced the worst thing that can happen to an owner—a horse she partly owned had to be put down on the track.“It broke my heart,”she says.“I ran onto the course—which is something you’re never supposed to do—tears streaming down my face. But I had to see him one last time.” Even though the horse was difficult—Rosenblum describes him as “gorgeous but nasty” and hard to control — the track death was a major setback, both professionally and emotionally.

But ballet had taught her more than how to dance. It taught her how to survive in a highly competitive arena, despite the long-shot realities, the naysayers and the contrarians. “When I was doing ballet, we used to joke that when you were up for a big part you had to check your slippers to make sure no one had put any glass in them,” she says.

Although she didn’t expect a welcome committee when starting in racing, she found herself in “an especially macho business,” Rosenblum says. “There was this attitude of, ‘OK. Let’s see what the new girl can do.’ ”

What the “new girl” could do was persevere. The learning curve was steep—sharply vertiginous might be more accurate— with more detours and headaches along the way. “I bought a number of yearlings [1-year-olds] and that was a mistake,” she says. Her beginning group of runners did not look promising, but she kept at it, saying that her love of horses sustained her: “I just adore being around them, in the stables, at the track.”

Her fortune began to improve in 2013 when Rosenblum teamed up with Linda Rice, the most decorated female trainer in the history of the sport. “Linda gave me credibility and was determined to make this work,” says Rosenblum, fondly remembering the breakthrough day in February 2013 when her horse Erik the Red (named after her son) won at Aqueduct with 34-1 odds, which was followed by the victory of Kara’s Match Point (named after her daughter) a few weeks later. These suc- cesses catapulted her stable into the winner’s circle for the first time and kick-started a streak of wins that has continued to the present day. Last year, the win average for Rosenblum’s Lady Sheila Stable was 34 percent (50 starts, 17 firsts).

The highlight of Rosenblum’s racing career came in January when her champion La Verdad won the 2015 Eclipse Award— considered the equine equivalent of an Oscar—for top female sprinter. After La Verdad took home the prize, the Daily Racing Form, the sport’s bible, wrote, “Few horses in recent seasons have combined the pure speed, admirable consistency and in- disputable class that La Verdad put on display throughout her 24-race career.”

Beyond partnering with Rice, Rosenblum attributes her recent successes to some hard-earned insights: how she learned racing is a numbers game, that it’s better to have several good horses instead of a single expensive racer. “Pedigrees are important, but there are so many variables,” she says, like “soul, talent, luck. Some horses are great natural athletes; others don’t even know how to break out of a gate.”

Her stable moved beyond its focus on yearlings to adding 2-year-olds closer to racing age. “Some can race as 2-year-olds if they’re ‘forward’ and have the talent, but successful ones at that age are few and far between. For many, it’s too much stress,” she says. She likes to compare the readiness to race to a dancer’s readiness to perform: “Even though young ballerinas are very muscular, their bones are still growing. You have to be careful how far you push them and that’s the same with horses. Linda and I like to work slower and give the horses more time to develop.” And even if a horse is ready to run at 2, she and Rice make sure it gets frequent breaks from the track. “At the end of the day, horses want to be horses, frolicking in a field somewhere outside the paddock. And they perform better when they have time off.”

Rosenblum’s goal is not only to keep her horses healthy and winning at the track, but also to make thoroughbred racing more attractive to women. “Most women don’t know much about it,” she says. While traditionally male dominated, the sport has had its share of iconic doyennes, like Lillian Phipps, Ethel Mars, Marylou Whitney and Penny Chenery Tweedy, who bred and raced the great Secretariat. Rosenblum says their achievements and tenacity have helped motivate her. “They worked as hard as men in racing and brought a major love for horses and glamour to the business,” she says.

Rosenblum has brought more women into the sport through her all-female syndications. Following the creation of Lady Sheila Stable, she formed her first syndicate, Lady Sheila Stable Two in 2014 with investors that include Dorothy Herman, CEO of New York real estate brokerage Douglas Elliman, and Jill Zarin of Real Housewives of New York. (Joining LSS2 required a $100,000 buy-in.) This first syndicate owns shares in four horses, including Matt King Coal, who was being groomed for the Kentucky Derby. A second syndicate, Triumphant Trio, was formed in 2015 in partnership with Rice and philanthropist Iris Smith and helped Rosenblum secure some major wins. This syndicate includes Champion of the Nile, sired by Pioneer of the Nile, who also sired Triple Crown champ American Pharoah. In addition, Rosenblum recently created her third syndicate, Lady Sheila Three.

To date, these groups have spent millions on horses. And while Rosenblum wants to increase the number of women in the sport, she’s very upfront about what’s at stake. “I thought there must be other women like myself looking to be involved in something that’s exhilarating, interesting, even a little dangerous. However, it’s high risk. We are dealing and competing with the top people in the business—billionaires and Arab sheikhs who can own hundreds of horses. We have just 25 horses, but our win percentages are very good.”

One of those top names Roseblum and partners deal with is Ahmed Zayat, owner of American Pharoah, with whom they entered a 50 percent partnership for an Uncle Mo colt (Uncle Mo ran undefeated as a 2-year old thoroughbred). There are high hopes as well for Matt King Coal, a 3-year-old colt, as well as Hot City Girl, La Verdad’s half sister and part of the original syndicate.

Meanwhile Rosenblum’s top earner La Verdad ($1.5 million) has been retired to breed and was recently covered (that’s equine lingo for impregnated) by Medaglia D’Oro, who has sired two dozen individual stakes winners. Now involved with breeding management, Rosenblum finds herself even more immersed in the sport. “I never thought I’d have the patience for it,” she says, referring to the lengthy equine breeding cycle—an 11-month gestation period followed by weeks of foal weaning.

Although fully committed to the thoroughbred world and an active equestrienne, particularly when she’s at her country house in Southampton, Rosenblum never rides her racers. Despite her stays in the horse-friendly East End, she doesn’t stable them there either. They’re kept at Belmont, under the watchful eye of Linda Rice.

Rosenblum does take part in one important South Fork horse ritual, the Hampton Classic—but only as a spectator. “That’s not about racing,” she says. Asked whether she ever gets flak from the horse show crowd for her involvement with racing, she points out that she is “as dedicated to horses’ health and safety, whether they are racing or leaping six feet into the air,” a reference to jumping competitions popular at these shows, which aren’t subject to the same scrutiny and criticism as racing.

Rosenblum admits that while the journey to the Eclipse Award podium has been a long one, she has no regrets about her decision to train, race and now breed horses. “The highs are very high, and the lows were very low. But I kept at it,” she says. In the process, she has earned the high regard of the industry, the media that follows it, and her competitors. She recounts having to scratch a horse from a race at Saratoga last summer because there was a small risk of injury. No less than Ahmed Zayet told her, “We have a lot of respect for your decision. You didn’t have to do that.’ ” To Rosenblum, “that meant a lot.”

As for the future, Rosenblum hopes for more visits to the winner’s circle and to see more women follow her into racing. “I want to bring idealism back to the sport,” she says. “And women can help me do that.”