Michele Oka Doner: Woman of Substance

Michele Oka Doner is under her favorite tree, a large banyan in Miami Beach a few blocks from where she grew up. She has chosen it as the place to be interviewed and photographed, during both of which she is multi-tasking, looking for vines she can take back to her studio to incorporate in her art. She played here as a child and returns to the tree as often as she can. Although in recent years it has been graffitied and burned, the towering majesty of its expanding canopy is still evident. “I once made an ‘Eve’ costume with its leaves for Halloween,” she laughs. Her name may not be familiar to you, but chances are you’ve touched a piece of her work, which includes important public art commissions all over the country. The works include Celestial Plaza at the American Museum of Natural History, Radiant Site, a New York subway station awash in gold and her crowning achievement A Walk on the Beach, an exquisite terrazzo and brass floor installation that extends 1.25 miles through Miami International Airport.

The concourse floor was executed in three sections made up of A Walk on the Beach, 1991-1995, From Seashore to Tropical Gardens 1996-2010 and Galaxy, the eye of the storm that joined them in 2009. The work consists of 9,000 brass and mother of pearl sculptures inspired by the flora and fauna of Miami Beach. It is indicative of Doner’s style, which is heavily influenced by science and anthropology. “It is about things you can’t see, cells in the water, bits of coral under a microscope, algae, seaweeds and shells,” says Doner describing the oeuvre. Although she now divides her time between her Soho loft in New York City and her Collins Avenue condo, Doner wrote the book on Miami Beach quite literally. She and good friend Mitchell “Mickey” Wolfson Jr, wrote “Miami Beach: Blueprint of an Eden” in 2004. In the striking coffee table book, Wolfson and Doner examine the city from its beginning in the 1920s through the 1960s using their prominent families, including Doner’s father, Kenneth Oka, who was first a judge and then Mayor of Miami Beach.

Doner starts at the beginning, sketching the grains of sand upon which Miami Beach was built, then showing us glimpses of pre-developed Miami Beach, original subdivision plans, photos of society culture, fashion, and local wartime efforts, ending with blueprints of famous theaters and hotels that exist now only in the author’s memories. The book uses memorabilia, telegrams and original notes on vintage stationary for a unique study of the times. There are also plenty of photos of their prominent families, movie premieres, dining clubs and a special shot of Kenneth Oka, Doner’s father with a visiting President Kennedy. Doner explains, “My father kept the development at bay. He wanted us to be like Rio de Janeiro, where the beach was open to everybody. Of course, the year he left, 1964, is when all hell broke loose, because the people who followed him were not as scrupulous.” Indeed, the mid to late 60s saw the rise of Millionaire’s Row on Collins, the condo canyon that replaced the calm, verdant avenue where Doner used to ride her bike as a girl.

[highlight_text] “For me, an artist is a thinker, a shamen and a transformer of materials.” [/highlight_text]

Although Doner has seen her hometown transform before her eyes, she is optimistic about its future and sees many parallels between the period of growth in development and population today and the post-war period in which she grew up. “The things I love are still palpable here. I can still go to the Everglades, take a walk on the beach, soak in the ocean, and watch the gulls fight over a fish. It’s such great theater.” These are the same things that shaped her art career, which started in earnest when she entered the University of Michigan in 1963, where, she notes, Craig Robins and Jorge Perez also graduated. “My dialog was constructed very early on, but in school I learned how to apply materials to it and share it with the world.”

Her work drew attention while she was still an undergrad, and later a graduate student studying for her Master of Fine Arts. It was the creation of Tattooed Porcelain Dolls, which featured disfigured baby dolls with disturbing tattoos, that first got attention as an anti-Vietnam war statement. Then came Death Mask on the cover of Generation, the University’s avant-garde magazine, although it wasn’t exactly what she had intended.

While she had the spotlight, she ran with it, creating many object and showing at a gallery near her home in Detroit where she began to make an international buzz. In 1981, with a husband and two young boys in tow, Doner made the move to New York, where she bought a spacious loft in Soho that she calls her “laboratory for living.” By 1987, she won a contest for the New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) to create a new subway station by submitting oversize plans for “Radiant Site.” Thus began her legacy of public installations.

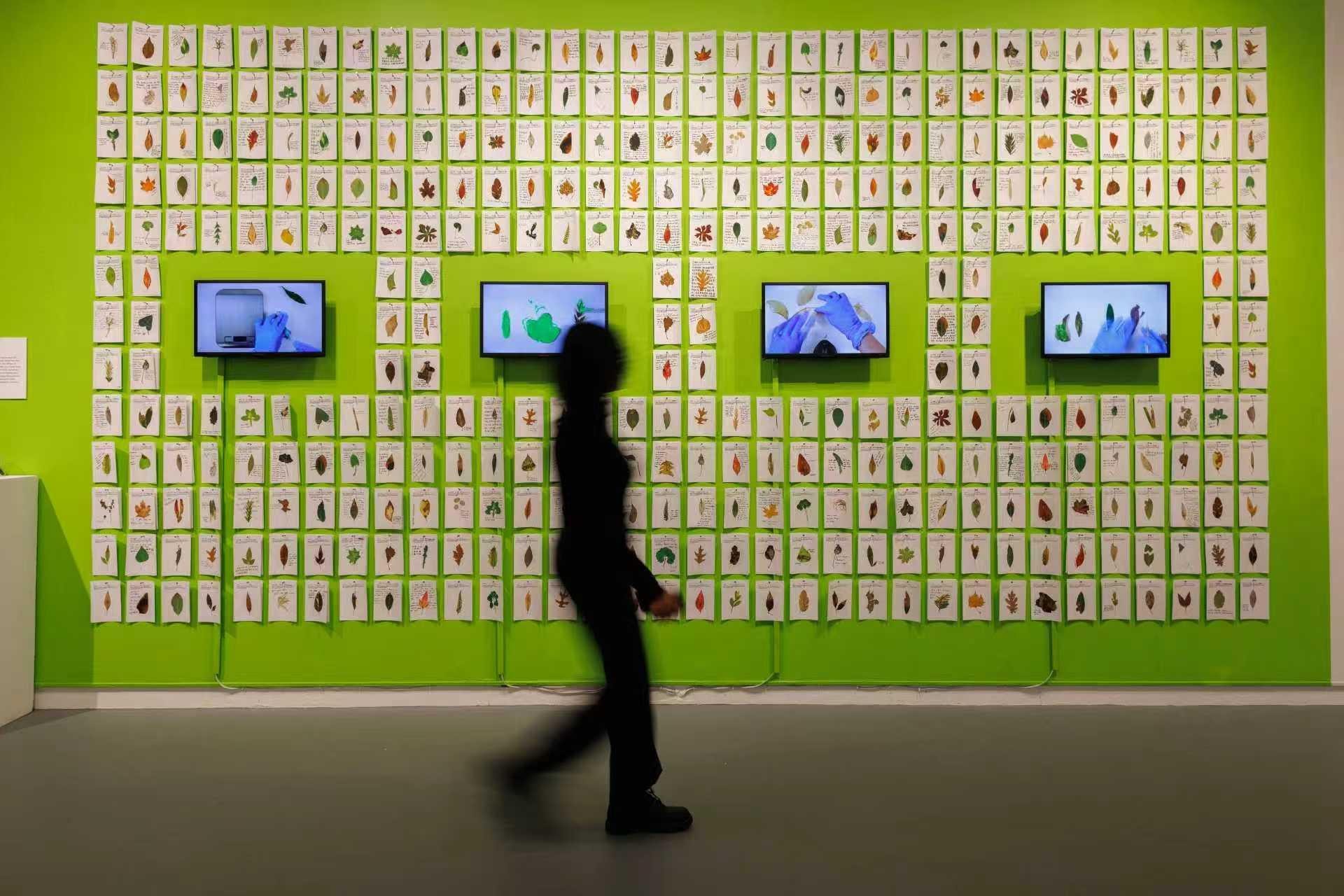

Donor references things most people leave behind in the classroom in her everyday life. She references Horace, gnosis, disjecta membra (the concept of putting disparate things together), cellular biology and scores of other things most of us have long forgotten. “I’ve been working for half a century and I’ve used a lot of materiality: wax, clay, wood, leaves, roots, bronze, gold, silver, paper, everything! I like to take things our ancestors did and explore all the possibilities,” she says.

[highlight_text] “It is about things you can’t see, cells in the water, bits of coral under a microscope, algae, seaweeds and shells,” says Doner describing A Walk on the Beach [/highlight_text]

She hasn’t left many stones unturned, but there are always new things on the horizon for her. “Annie Leibovitz is coming to photograph me next week,” she says casually. “And I’ve got a new mural going up in the Apogee,” she says referring to Related’s Apogee project in Hollywood. Bruce Weber already photographed her for Italian Vogue earlier this year. She recently completed an installation outside of Doral’s City Hall, and in 2011, premiered A Walk on the Beach, the movie on the New World Symphony’s 7,000 square foot wall. Of course, Marlborough, her gallery of more than a decade, will be showing her work at Art Basel Miami Beach, which has a loyal following of avid and prominent collectors only a few hundred yards, but a world away from her favorite tree.

Photos by Alissa Christine