How Padma Lakshmi Is Stirring The Pot In The Second Season Of Hulu’s “Taste The Nation”

TROUSERS, SHOES, SHIRT: Padma’s own

Photo Credit: Luke Dickey

PADMA LAKSHMI IS DECONSTRUCTING AMERICA’S CULTURAL MELTING POT IN THE SECOND SEASON OF HER HIT HULU SERIES, TASTE THE NATION.

BY LAURA SCHREFFLER

PHOTOGRAPHY LUKE DICKEY

STYLING FAISAL HASAN

HAIR REYNA G.

ART DIRECTION AMIR ZIA

SHOT ON LOCATION IN NEW YORK CITY

For all intents and purposes, Padma Lakshmi shouldn’t be approachable. Even sitting on her bed, in oversized glasses, post-gym, and totally makeup free, she is impossibly, effortlessly beautiful. She is an obviously intelligent, Emmy-nominated food expert, television producer, host, and New York Times bestselling author who speaks not one, not two, but five languages, and … well, let’s just say it wouldn’t be off-base to think that the Top Chef host is intimidating as hell.

“I really hope not!” she declares when I air this thought out loud. “I spend a lot of time — especially when I’m filming — trying to make people feel comfortable. I don’t think I intimidate. I mean, I try to be as warm and approachable as I can, because I remember being intimidated by a lot of people growing up. I think on Top Chef, for so long, my position and my role on that show caused people to think I was more intimidating than I am — I had to be stoic in my role — but that’s not me normally. That wouldn’t be me if you and I were friends and went out to have brunch or something.”

Warm and fuzzy aren’t quite the feelings du jour that need to be served up on Top Chef, the hit Bravo show Lakshmi has hosted since 2006. But, when it comes to Taste the Nation with Padma Lakshmi, the Hulu docuseries she created in 2020 that is returning for its second season on May 5, she absolutely needs to be Miss Congeniality. After all, there’s a big difference between judging media-trained professional chefs and speaking to the immigrant population of America.

“You know, it was a new skill for me to interview people,” she admits. “I mean, I’m a food writer. Before Taste the Nation, I could count on one hand the times I had to interview people, and those were at a literary festival or a food festival — it wasn’t for anything very high stakes. It was something I had to learn on set, and I’m still learning.”

It may be a new skill for the 52-year-old multi-hyphenate, but you’d never know it. In her series, Lakshmi is natural and authentic in her interactions with local businesses, chefs, and families as she makes her way around the country, exploring how — through a single, defining dish — each community’s culinary traditions have shaped our country.

“I think the reason I learned [how to become an interviewer] so quickly is that I’m genuinely interested,” Lakshmi confides. “The whole show is created around all of my various interests: history, food, people, languages, traveling. I’m genuinely curious.”

That very curiosity took her everywhere from Milwaukee to Honolulu in season one and continues to grow in the series’ sophomore effort. The first episode of the new season takes Lakshmi to Puerto Rico, where she explores the U.S. territory’s fight for independence by examining a surprisingly controversial topic — whether or not to use ketchup on traditional pasteles — a dish consisting of root vegetable dough filled with a savory meat stew and wrapped in banana leaves. Other foods and cultures highlighted in the new season include the feasts of the Afghan American community in Washington, D.C.; the inventive recipes and simple ingredients that shape Appalachia; the symbolism of borscht for the Ukrainians of New York’s Brighton Beach; and the significance of avgolemono for the Greeks of Florida’s Gulf Coast.

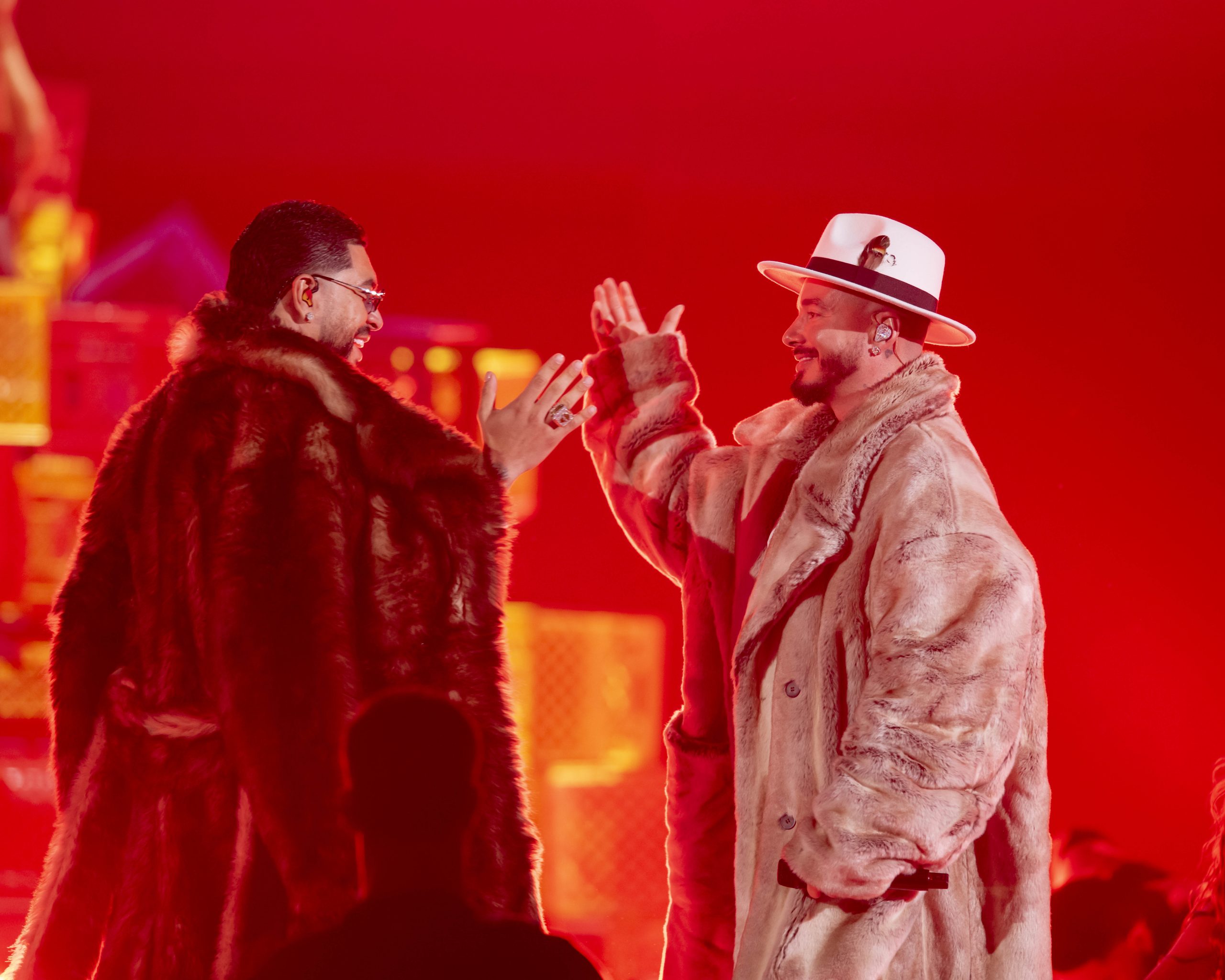

TOP: Timothy Gibbons

SKIRT:Vintage Roberto Cavalli

Photo Credit: Luke Dickey

“We try to approach every community with fresh eyes, because I didn’t just want this to be a survey show where you go into a community, learn about their food, have your questions answered, and then repeat. I really wanted to tailor each episode around some aspect of an immigration issue that we could learn from,” she says before referencing the second season’s premiere episode. “For instance, we handle the issue of food sovereignty and sovereignty in general in [“Ketchup or No Ketchup”]. People don’t think of it that way, but [Puerto Rico is] the last U.S. colony; we are the colonizers of Puerto Rico. But some people think of Puerto Ricans as immigrants … and they’re not. We went to their land, you know? They are American, too. And [with this show], we were able to talk about that, to make that point.”

She cites “On the Tip of My Kreung” as one of her favorite episodes. In it, she explores the Cambodians (and their cooking) of Lowell, Massachusetts. “That was really my answer to people who say, ‘Refugees and asylum seekers drain our economy, take away jobs from others, and don’t help the communities in which they live.’ Well, Lowell, Massachusetts, was a very different place 20-30 years ago. It was gang-infested — a crack and meth pod. Nobody wanted to live there; there were many shop fronts that were boarded up and vandalized. When Cambodian refugees came over here, they didn’t speak the language, they didn’t have advanced degrees, they didn’t have anything but the shirts on their backs, and yet, they revitalized the town of Lowell so that the economy there is looking up and the school system is better. One in four citizens of Lowell are actually Cambodian now, and that, to me, is a beautiful and uplifting story that everyone needs to hear, and not a lot of people have.”

That’s why Lakshmi created Taste the Nation in the first place. “I didn’t hear these stories being told. I mean, I grew up in an immigrant community, and I started working with the ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union] in 2016 because there was so much vitriol coming out of Washington from Steve Bannon, Stephen Miller, Trump and his whole campaign. He was trying to stoke xenophobia and demonize immigrants. Those stories were just not true, and they did not reflect the immigrant communities that I lived in. It made me so mad that I started working with the ACLU on immigrant issues, and then after a while, I just wanted to do something creative in my professional career that would allow me to take my advocacy and do something artistic with it so that I could show you what I meant through these people and these stories, rather than just get on my soapbox and tell you at a speech or a rally.”

And because she realized that this kind of visual medium would be more impactful than a virtual or metaphorical soapbox, she sought to make the series as interesting as humanly possible — something she herself would want to watch. “A lot of it is like, ‘What kind of food do I want to eat?’ and ‘Who seems cool?’ and ‘Who hasn’t been done?’ There’s a gorgeous, big Vietnamese community in New Orleans. I haven’t covered it yet, but a lot of other people have. So, then I think, Well, how can I cover it differently than other people have? How do I make it sexy? You want to keep people’s attention, you want to entertain them, you want them to have fun, but you also want them to have some kind of takeaway. It could be something as simple as, ‘Oh my God, I’ve never thought of stir-frying that way,’ or ‘Gosh, I never thought about Puerto Rico being an American colony, even though we call it a territory,’ or ‘That’s not fair, why don’t they have elected officials in Congress who can lobby for their needs like every other state?’ And that’s what I’m trying to do with every episode — trying to do more than one thing so that it hits you on different levels: on the food level, on the human level, on the emotional level. Hopefully, you’ll find it to be beautiful and that it will have taught you something by the end of the 30 minutes that you didn’t know before.”

But what has the show taught her? As Lakshmi says, she’s always curious and always learning. “I think what it’s taught me is that the faces of America are very varied, but that doesn’t mean they’re any less American. It took me a long time to feel that way. Growing up, I always felt like an outsider in America. I felt like, Yes, I’m American, but I’m not as American as somebody who’s a Euro American, who’s white or ‘waspy’ for lack of a better word.” Born in Madras (now Chennai), India, Lakshmi moved to America with her mother at age 4 when her parents divorced. They lived in Queens, New York, before moving across the country to a mixed, mostly Mexican and Filipino neighborhood in Los Angeles. She explains that, each summer for three months, she would return to India, but she never felt particularly Indian. Just as, when she spent those nine months of the year in the States, she never felt purely American. And so, though she identifies with both cultures, she felt like a master of none. “I always had one foot in each,” she admits.

It wasn’t until Lakshmi turned 39 and started a jewelry line that she began to realize that she could merge both cultures, and that being part of each made her unique. “I was taking a lot of inspiration from jewelry I had seen other Indian women in my family wear, or what they wore in classical Indian paintings or sculptures and [in] temples. But it wasn’t ‘ethnic’ jewelry or anything like that; it just had a bunch of eclectic influences. I realized then that it was possible to blend the best of both, and to be both at the same time. Unless you’re an indigenous person or a Native American, you, too, are a blend of things, even if your ancestors came over on the Mayflower. I think we forget that.”

PANTS, SHIRT & BRA: Padma’s own

Photo Credit: Luke Dickey

But her true “aha” moment came when she was doing an office blessing for good luck with priests that she had invited from the Hindu temple in Queens. “That was really the first time that I thought, Yes, I can reconcile all the different facets of my identity into one human, because I am one human, and I do have all of those parts to me, which are all important.” She pauses momentarily before musing, “Even if you don’t feel like that, even if you are always feeling like you belong and always had everyone who looked like you around you, I think — as women — that happens anyway as far as identity. Are we mothers, are we sisters, are we daughters or wives? Are we professional women? Can we be both? Can we be more than one thing?”

Ah, the eternal question. Here, I point out that the world at large certainly doesn’t feel like women can be chefs — there are so few out there. The culinary profession still, after all this time, is one that is largely dominated by men. And she, as not just a food writer, but the host of Top Chef, is uniquely qualified to speak to this.

“I think the profession isn’t conducive to having a home life. Cooking is very much a science and also an art, but it’s also manual labor; you’re just standing there in a hot kitchen, and it’s physically taxing work. So, I think it prevents a lot of people from entering that workforce for any length of time. Women are there, but then they drop out, or they don’t get to a certain level because they need to make dinner at home for their families,” she explains, bringing the topic around full circle to the point she’s making and the narrative she’s telling with Taste the Nation. “I think every facet of our culture is ruled by the patriarchy, and the patriarchy is built on one group of people subjugating another group of people to keep an unequal balance of power … because that is how capitalism also works. Capitalism and patriarchy are very intertwined.”

The patriarchy conversation leads me to ask about a like-minded, male-helmed series: I wonder if she’s received comparison to the late, great Anthony Bourdain, and her show to his Parts Unknown. The answer is “yes,” but she’s loathe to make that connection herself. This is her thing, and her thing only.

“I do [receive comparisons often], and I’m always flattered. Tony was a friend. I knew him for about 20 years, and I admired him a lot. But I think we’re really different. I’m not going to bite the head off a chicken or eat a beating heart. You’re not going to see me do that, because I would rather die, you know? That’s not my personality. Nobody can be Tony, and [similarly], nobody can be me. I’m me. I don’t want to be like him; I want to be the best version of myself. I am a woman, I am a mother, I am an immigrant. I bring all of that baggage to work with me every day, and the show is informed by all of those things.”

Photo Credit: Luke Dickey

Just as Padma Lakshmi is surprisingly approachable, she’s entirely relatable, too. For example, she’s talking about how she and her now-13-year-old daughter, Krishna Thea Lakshmi-Dell, stayed up until the wee hours of the morning binge-watching the Netflix series Never Have I Ever.

“Krishna and I inhaled that show after a premiere of Top Chef during quarantine; we started watching it at 11 and we finished it at 4 a.m. We binged that show. It was so wonderful to hear a mother call her daughter ‘Kanna,’ which means ‘Dear’ or ‘apple of my eye’ [in Tamil]. That’s what I call Krishna, that’s what my mother called me, and I’ve never heard it before on American television.”

Although she is obviously Indian and being Indian is a part of her identity, to be sure, I point out that it doesn’t seem to be the most predominant part. Never Have I Ever creator Mindy Kaling, for example, comes from Indian lineage but was born in America. The opposite is true for Lakshmi.

“I think Mindy is trying to write shows for people who never got to see themselves on TV, which is why Never Have I Ever exists and why it’s so brilliant. I’m hugely in awe of her. [Similarly], I think being Indian is a part of me, but it’s also not all of me. For example, I spent all my 20s in Italy. So I also feel very Italian, you know?” (Sidebar: her 20s and love of Italy also were the impetus for Taste the Nation’s second season episode entitled “Ciao New York” — a way to reminisce about “la bella vita” and eat some thin crust pizza.)

And while she may not be outwardly projecting her roots, her heritage, as she says, is very much a part of her. “Being Indian influences everything I do, from how I raise my child to how I make people take off their shoes when they come to my house — which is very Asian — to how I oil my hair every week. I just don’t wear it on my sleeve,” she says, noting, “I am Indian, so I don’t necessarily have to make being everything Indian my identity, if that makes sense.”

Photo Credit: Rebecca Brenneman/Hulu

It does, and it just proves that point that Lakshmi has been making all along: none of us is any one thing, and we are all more alike than we think. That being said, when it comes to Lakshmi, there’s a twist — she definitely is more accomplished than most. And that should definitely not be taken away from her.

Not only did she create Taste the Nation, which won a James Beard Award for long-form visual media, but she’s the co-founder of the Endometriosis Foundation of America and is an ACLU artist ambassador for immigrants’ rights and women’s rights. She was appointed a goodwill ambassador for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); has hosted two successful cooking shows in Padma’s Passport and Planet Food; and has written several books, including the bestselling Easy Exotic, as well as Tangy, Tart, Hot & Sweet; her memoir, The New York Times bestselling Love, Loss, and What We Ate; The Encyclopedia of Spices & Herbs; and the children’s book, Tomatoes for Neela. She is also a visiting scholar at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and — oh yeah! — has been host and executive producer of the two-time, Emmy-winning Top Chef.

And on that front, there’s only one true issue: despite the series’ Emmy wins, she still doesn’t have an actual statue, even though she’s been a producer since 2013. And so really, besides that little golden woman trophy, the only thing Lakshmi doesn’t have these days is the thing she craves most: time.

“I wish I had more time in the day to get a regular pedicure, to read more. I know it sounds very boring, but to me, that is the greatest luxury. I’m a very slow reader, but I love to do it, and all I want to do is sit like a bump on a log and slowly read a book or a newspaper from cover to cover,” she admits before sharing a universal truth. “Sometimes when you get the success you’ve always wanted, you often don’t have time to enjoy it. They should tell you that.”

Photo Credit: John Angelillo/Hulu

But would she change anything had she known what her life might look like, and how little time she’d have for pleasures, however simple? The answer isn’t quite so easy. “I am enjoying [my success], but I don’t know … I’m just tired,” she admits with a light laugh, continuing, “I think at different times in your life, there’s time for work and there’s time to take it easy. I think that I wouldn’t be here unless I had worked so hard and made some of the sacrifices that I have made. But I also think that now I do want to take it a little bit easier. I do want some more time. My daughter is 13; I want to enjoy her before she goes to college. I only have five years left with her, and that preys on my mind. Last year, I was on the road from February to October, and my grandmother died literally a week before I left. I don’t think I had enough time to mourn her, but working so much also was a blessing because it gave me something else to think about. So, I do want to work just as hard, but I want to be selective and minimize the number of things I do. I want to do fewer things, but better.”

What she’s doing with Taste the Nation is a perfect example: not only is the series good, but it’s doing good at the same time. And while she may not have much time, this is one thing she plans on continuing to put her all into. It’s a tough job, teaching the world, but someone’s got to do it.

Lakshmi agrees wholeheartedly. “There are a lot of things that are getting worse in the world, but I think we’re getting better at creating diversity, showcasing that there’s something for everyone. We, and the people that are in places of power, are learning that there is validity to showing different kinds of stories. And I’m here for all of it.”

TOP: Timothy Gibbons

Photo Credit: Luke Dickey