Nicolas Berggruen: International Man Of Democracy (And Mystery)

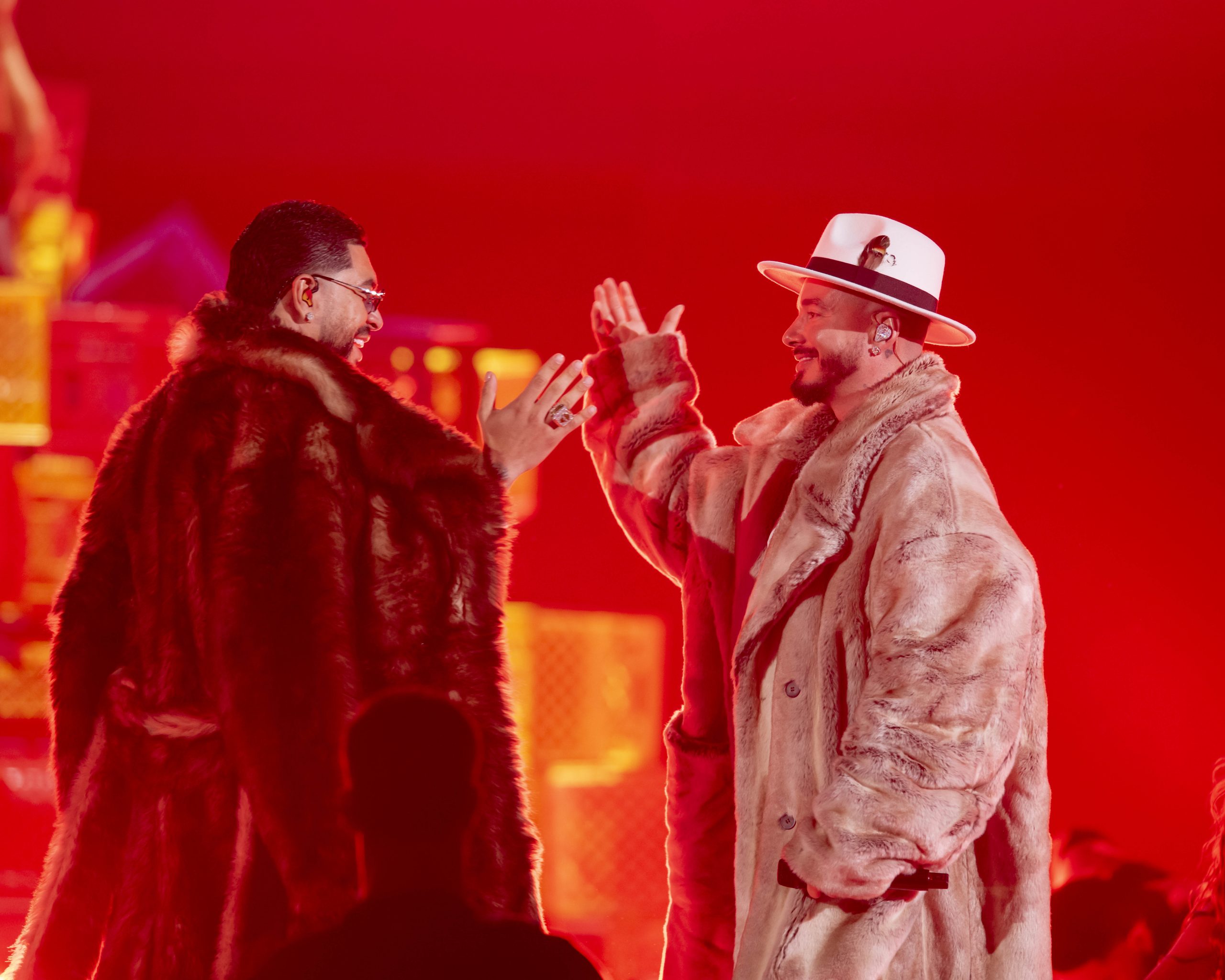

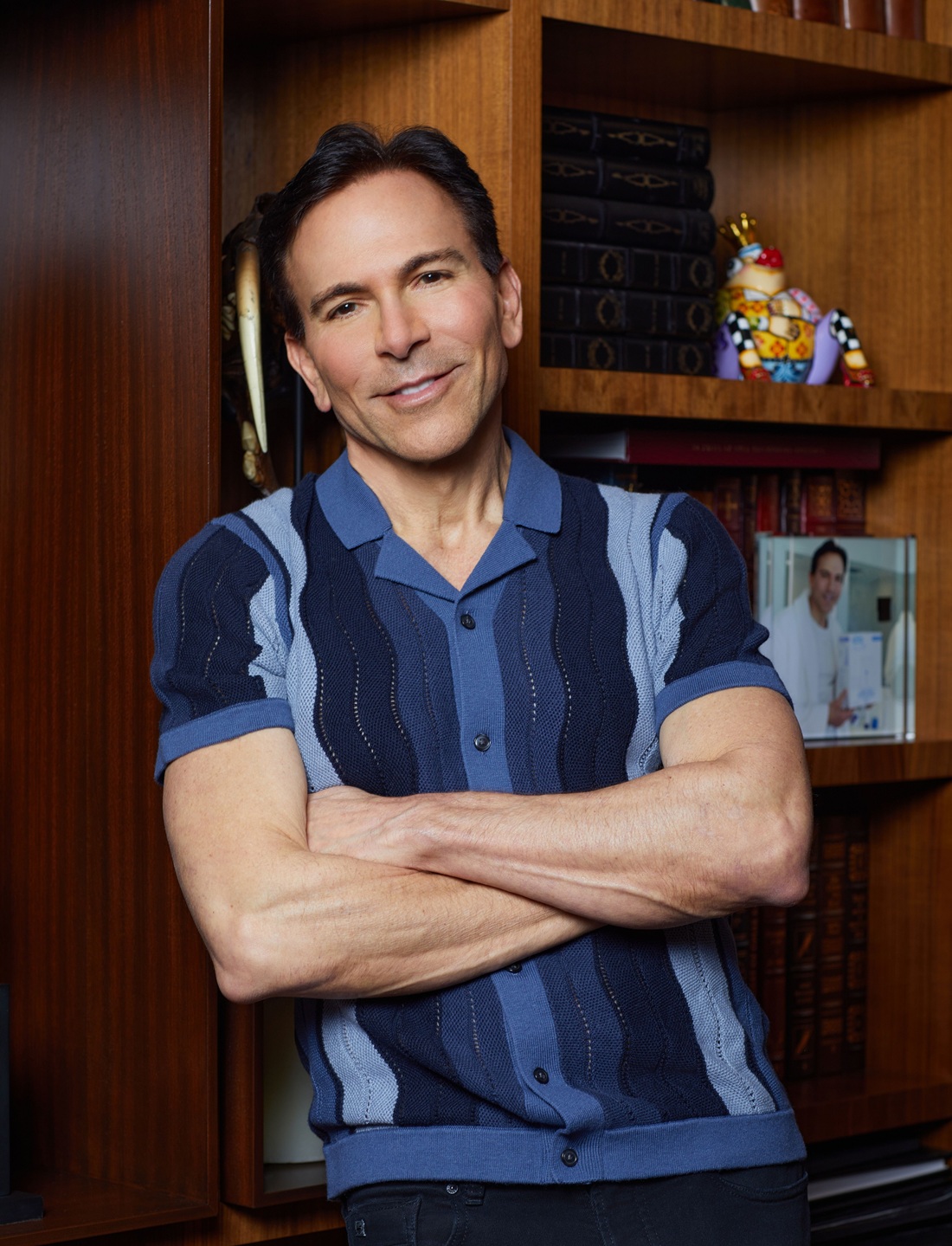

Photography: Frederic Auerbach

Styling: Dex Robinson

Grooming: Darren Hau

Shot on location at The Bradbury Building

Something tells us that Nicolas Berggruen would make a really amazing poker player. Not only does he nonchalantly slip on a pair of sunglasses the moment we arrive at his London hotel suite (effectively hiding his eyes, those pesky, tell-all windows to the soul), but his answers are often confusingly in no relation to the questions asked, especially when the topic veers to the personal. Meaning, he’s wily—and will talk in circles to avoid talking about himself.

That the 57-year-old billionaire investor and philanthropist is unfailingly private is no secret. He regularly deflects questions—both personal and professional—maddening media moguls, politicians and more with his elusive manner and cryptic, philosophizing ways. But we understand what he’s doing, why he only provides the most minuscule glimpse into his daily life, be it with actual human interaction or via social media: By controlling the conversation, he’s providing a structure that works for him, allowing his ideas to become the focus of the conversation around him.

Or so he hopes. Berggruen is an enigmatic figure, sunglasses or no. There’s his all-black uniform of a T-shirt and jeans that he infrequently departs from (today is no exception); the German accent subtly sprinkled with a dollop of French and a sprinkle of American, a nod to his upbringing—he was born in Paris—and dual citizenships in Germany and America; his affiliation with the arts—he sits on the board of the Berggruen Museum in Berlin, a member of LACMA, the International Councils of the Tate Gallery in London and MoMA in New York; that he has two children, both by surrogate; and his playboy past, living in some of the top hotels in the world.

But these are mere details and are not indicative of who he is as a person. And because of this mystery, we need to know: Is the mysterious figure he projects at odds with the person he really is? “I am likely more introspective and interested in the less traveled and explored,” he tells us evasively.

And while Berggruen the man may remain a question mark, we aren’t here inside his Claridge’s hotel suite to give Berggruen a personality quiz. The topic of today’s discussion—coincidentally mere days after the first Democratic debates—is his latest literary effort, Renovating Democracy: Governing in the Age of Globalization and Digital Capitalism, a collaboration with his Berggruen Institute co-founder Nathan Gardels.

In this analytical discourse for rethinking how democratic systems work, Berggruen lays out the steps necessary to implement change. Those are democracy—rethinking the system; capitalism; how to build a sustainable future for the planet; and how we can reinvent ourselves in the age of artificial intelligence and gene editing.

“The book specifically tries to work on the state of our democracies. Democracy, in general, has conquered half the world—it’s been incredibly effective—but you can see now that any system, even if it’s the best system, needs renewal,” Berggruen explains. “Democracy is really about giving individuals a place in society, a voice—respect, in some ways—equality as humans. It’s also a system. It’s not every individual for themselves; it has to be society as a whole.”

But is, as headlines suggest, American society broken beyond repair? We don’t expect a simple answer to this, and Berggruen doesn’t give us one. “I think there are times when the country comes together, like every country,” he says. “I think we’re at an unusual time when divisions are very high. It’s like a pendulum, one extreme to another, but at some point, we’ll come back together. We have no choice.”

Is that strictly true, or just a comforting thought? For Berggruen, it’s not just a belief, but a universal truth. “I think that America and other democracies today are experiencing the same phenomenon, which is a very divided environment; everything is very politicized beyond what might be needed,” he notes. “We need to rethink how we function. It’s not beyond repair—it just means we need to address [the problems]. People need to feel like they’re part of the future. [Our division] is very unhealthy. It’s not constructive and it doesn’t bring contentment, which I think is important in advanced societies. We’re so rich—we have so many tools—if we can’t make sure that we provide the human minimums for everyone, then we’re failing.”

Photo Credit: Frederic Auerbach

Photo Credit: Frederic Auerbach

With the 2020 presidential election looming, it’s a pointed time to release such an analytical look at how the world as a whole could be fixed. Almost as if Berggruen were saying, “See? This is what has to happen if you want to make not just America, but the world, great again.” Here are the steps, here are the tools—now fix it.

“How do you give everyone a voice today? How do you do that in a way that brings people together, as opposed to apart?” he wonders. “What’s fraying today is the engagement between citizens and the community and citizens in government. There’s an enormous distrust in government. Government is needed, but it should be a service organization, not a political instrument. More and more it’s treated like a political football, and it’s not really of service to citizens if every issue is politicized. You can’t just put everything up for grabs every day. You need to say, ‘All right, you participate, and at the same time you delegate.’ That’s how democratic systems have worked.”

The book, like Berggruen, is largely unbiased, providing a frame of reference for what is broke and solutions as to how things might be fixed. It doesn’t point fingers at any one nation or leader, though some might suspect it should. When we recall reading a recent headline proclaiming “America is toast,” he responds, “America is the most prominent example of a divided or a chaotic domestic environment, but it’s not unique. Look what’s happening in the U.K. [with Brexit and its new prime minister]. The country I was born in, France, is experiencing difficulties and division, as well. It’s pretty much everywhere.”

When it comes to his own political affiliation, he’s unbiased, as per the ethos of his nonpartisan Berggruen Institute. To put it simply, he’s Switzerland (literally and figuratively―he went to boarding school there).

“We at the Institute don’t get involved—on purpose—in elections; we would lose our neutrality,” he says. “We’re interested in things working for the community, not for one group or another. People are so focused on the candidates… but at the end of the day, the people who get elected are a symptom of what’s happening in society—including [President] Trump. Depending upon who gets elected, you might have an easier pass or a harder pass fixing overall issues, [so when it comes to the official elected] I do think that’s relevant. Sometimes, you need a shock to the system for people to realize that something’s broken and that they’ve got to work on it. Right now, we’re in a position of transition and chaos. We have to reinvent the way we function, and I think that that’s what these messy politics show.”

It’s a classic catch-22: Although new ideas are needed, candidates need to win. This is a conflict, because many politicians make empty promises to win, which not only creates conflict, but does not perpetuate change. “[Political candidates] are so focused on the short-term—emotional issues and what they can sell to voters—that unfortunately it’s much harder to address the big long-term issues, and they don’t have time to think about the fundamental issues and problems that face us. They’re generally just focused on getting elected,” he notes.

Photo Credit: Frederic Auerbach

Photo Credit: Frederic Auerbach

Not that this matters: In his unbiased opinion, there is no one president, no lone leader, who can fix what has been broken; citizens need to be the change on their own. “I don’t think it’s so much a question of leadership,” he maintains. “This is the point of the book: We have to get ourselves back to the point where the system is reshaped, so it allows [for the healing to begin].”

If he’s telling the truth (or directly asked—same, same), he will allow of America’s fearless tweeter: “Donald Trump, because of his personality and the way he manages things as a president, is not a calming force, to say the least. He’s very combative—fueling the fire is his style. But the media also fuels the fire, so it feeds on itself.” In other words, for someone who thinks big picture, this consistent backdraft isn’t sustainable. “It’s fine for a period, but as a constant way of operating, it becomes toxic after a while,” he says.

On the flip side, if there wasn’t already a fundamentally flawed system, Trump might not have been elected in the first place. “Trump came after Obama two times. If things were perfect and stable to begin with, [we wouldn’t be having so many problems],” Berggruen points out.

He does, in a much, much less extreme respect, agree with Trump that immigration restrictions—or “reasonable accommodation”—are necessary; matching the skills and education levels of incoming immigrants with an appropriate host economy. “Immigration needs to be tailored to the culture,” he muses. “Some cultures are quite open, some are not, and even then it depends on what kind of immigration. You have to make sure that immigrants add to the strengths of the country. But in truth, countries that have allowed immigration have been much more dynamic. Immigrants, in general, bring energy and a hunger for the future. Countries that were built that way—like the U.S.—have benefitted enormously through immigration. You just have to have standards, filters and allow legal immigration.”

And although he doesn’t have much to say on its immigration policies, the country that fascinates Berggruen the most, without a doubt, is China. “China is an important element in terms of how we have to think of our democracies,” he notes. “For the first time, we have a real competitor.” He means, specifically, that as a whole, the Asian country has a much more solidified long-term plan for its progression and sustainability in place, with visible results—despite its lack of democracy and communist leadership.

“I’m not saying that we should be like China,” he explains. “In fact, [I’m saying] the opposite―cultures aren’t so easily transferable. But we have to take another culture and another political system seriously. China’s not about to disappear. What China does should wake us up a little bit, to see that for the first time we have competition.”

Photo Credit: Frederic Auerbach

Photo Credit: Frederic Auerbach

We note that when it comes to social media—a subject that he touches upon several times within Renovating Democracy, the opposite would appear true, as the Chinese government controls content by blocking social media apps such as Instagram and Facebook, and carefully monitors the apps and sites that aren’t blocked or banned—which completely goes against American democratic rights. But whose way is right? “In China, social media is the pulse of society, and it is integrated between civil society and government,” he explains. “It’s almost transparent with good and bad. We’ll never accept this here [in America]; it’s total chaos, and governments are way behind the networks. We’ve lost control of what’s happening in society. They have too much control, and we have too little. What is the answer? Probably somewhere in the middle. Our privacy shouldn’t be violated, but at the same time these networks are so powerful that not having a social contract between these networks and society is creating the anxiety and unsettled and divided nature of our [country] today.”

He’s not saying China is perfect. Its long-term planning, however, is a different story. “China has issues of its own, but they can enforce cohesion by forcing it, and they can also plan and function in a longer-term way,” Berggruen states. “The way we operate in the West forces us to look at everything very short-term, and that puts us at a disadvantage.”

His fascination with China and its governing body not only led him to request several meetings with the country’s president, Xi Jinping, but to also create the second branch of his Berggruen Institute, The Berggruen China Center, in Beijing at Peking University (the first being his flagship at home in Los Angeles). It’s a hub for East-West research and dialogue dedicated to cross-cultural and interdisciplinary study, as well as technologies focused on AI, the microbiome and gene editing.

“It’s not by chance [that we built this in Beijing],” he explains. “We went to the two extremes culturally and politically, China and the USA, to establish the two centers of the Institute. At a time when there’s a real clash of civilizations, it’s even more important to maintain a connectivity or communication between those civilizations.”

And while Beijing and its Eastern sensibilities hold the most interest currently, Los Angeles is his true love. The sentiment “home is where the heart is” rings true for Berggruen: After decades of bouncing around the world from one luxury hotel to another, Berggruen has finally settled down in the City of Angels and purchased property in West Hollywood. It is also where he chose to locate the Berggruen Institute, currently nestled inside the historic Bradbury Building in Downtown L.A.

Berggruen is now planning a new headquarters for his Institute, designed by the Pritzker Prize-winning architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron, along with Gensler, landscape architects Michel Desvigne and Inessa Hansch and design partner Mia Lehrer of Studio MLA. The project is described as a contemplative Scholars’ Campus rooted in the natural environment. It will house the Institute’s educational programs, fellows and scholars, and is designed to honor the adjacent land in the Santa Monica Mountains and protect the vast majority of the property’s 447 acres as open space.

As you can see, Berggruen is putting down roots. He calls Los Angeles the “best place to live on Earth,” referencing its diversity, openness and mixture of cultures as primary reasons for his affection. “It’s a city that’s still in the making. It has talent and creativity in a dozen different areas as opposed to one or two, and it’s at the intersection of ideas and technology more so than any other place.”

Photo Credit: The Berggruen Institute and University of California Press

Berggruen, who turns 58 in August, admits that moving there was “part of a personal journey. I grew up in Paris, lived in London, then New York for a very long time, and now in Los Angeles. I got there organically. In Los Angeles, I came back to what I was interested in when I was a teenager living in Paris, which was philosophy and politics. I spent time with professors at USC and UCLA. One thing led to another. I was interested in ideas, put together a little group to think about these issues, wrote a first book and then we created the Institute.” And there could be a third leg of his think tank, based on his natural wanderlust and heritage alone? “Could we think of a third leg in Europe or in the U.K.?” he wonders. “We might.”

It would seem, in this case, that his personal and professional journeys might be one and the same. It’s an exciting phase of his life, a time period that he refers to as “always exploring.”

“Being alive, for me, is to explore everything imaginable during [my] life,” he says. “Traveling is incredibly exciting. You learn about yourself, you learn about others; the possibilities of what it is to be human. Traveling is really a way to open your eyes—enforcing change—and forces you to improve who you are. It’s like the journey of life itself, but it makes the journey more interesting, richer, more provocative. When you travel, you’re confronted with the other, the new, alternatives. It makes you question your own beliefs and gives you a sense of wonder because somebody else has created something that’s startling. Good or bad, but it will have an effect on you.”

And right now, he’s traveling—right out the door. He leaves us with a hope for his legacy—“To have enabled the generation of ideas at the service of humanity [as well as] my children”—and the greatest luxuries in his life—”Time, space and the ability to disconnect and connect”—as he walks out the door, his black jacket slung casually over one shoulder, James Dean style, a rebel with a cause, ready for wherever this day’s adventure will take him.

He doesn’t take off his sunglasses, and we never see his eyes but he is smiling and we’re reminded that there is a crack in everything—it’s how the light gets in.