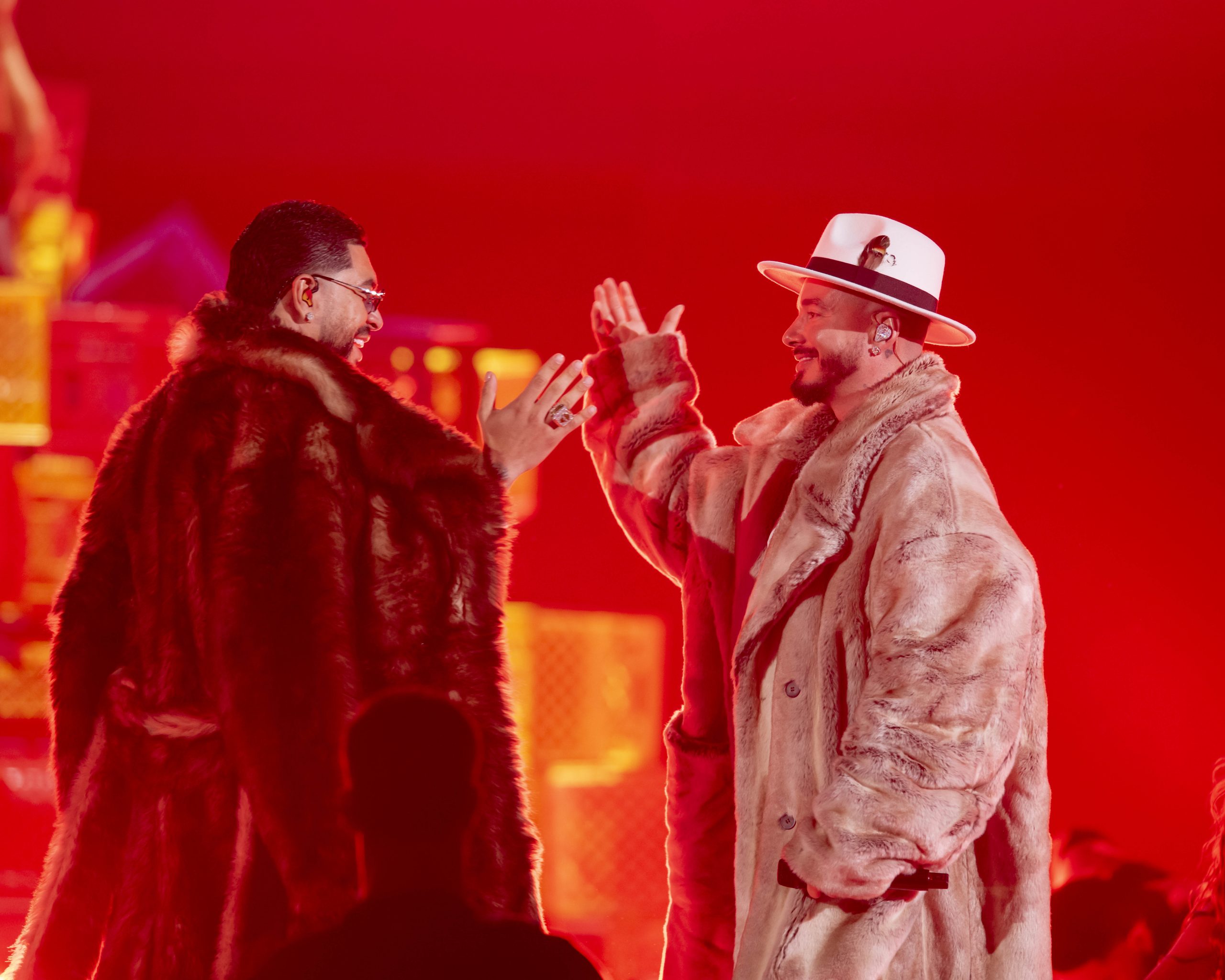

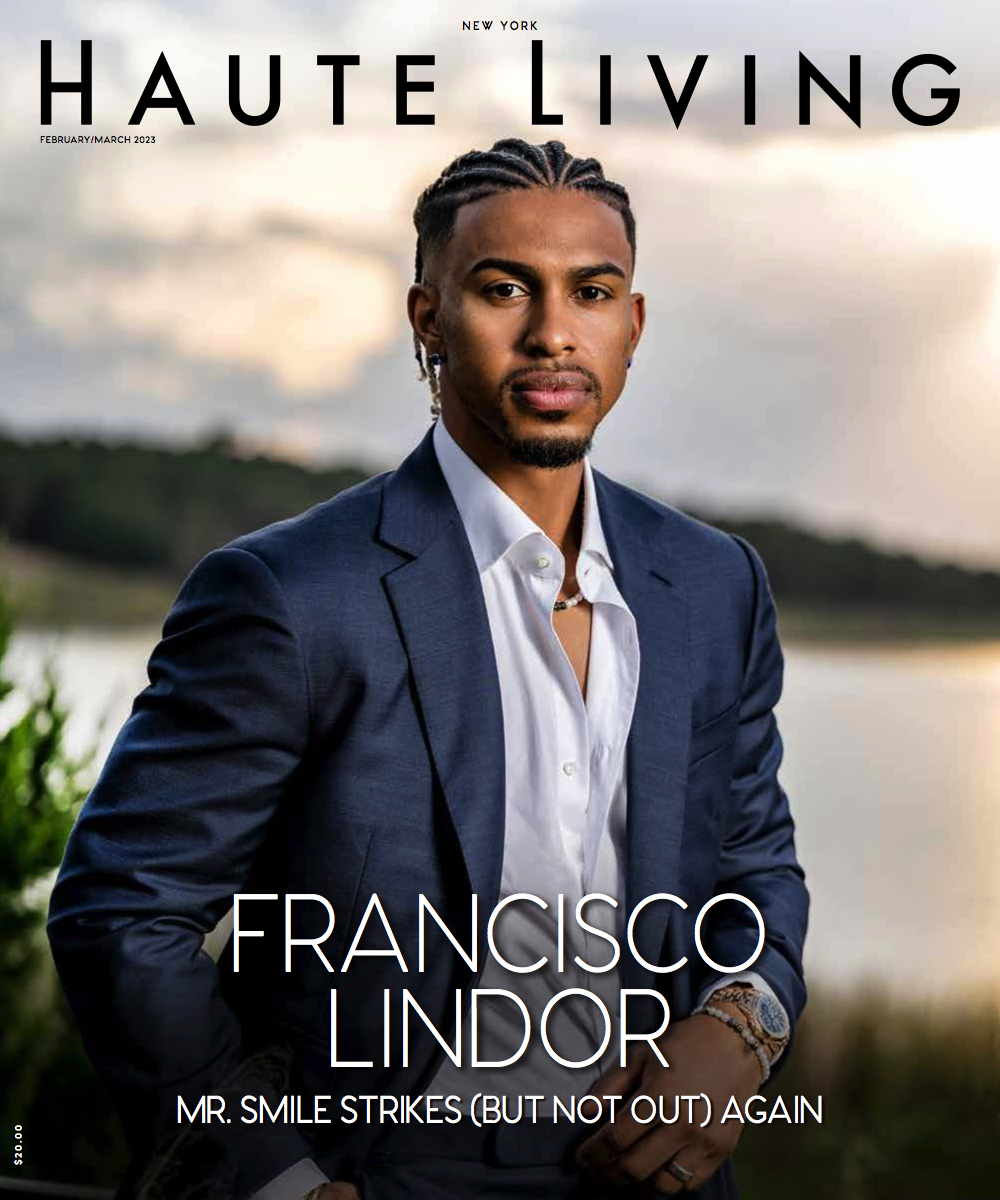

Francisco Lindor Sleeps Easily Every Night — Clad In Designer Watches

SUIT & SHIRT: Ralph Lauren

JEWELRY: David Yurman

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

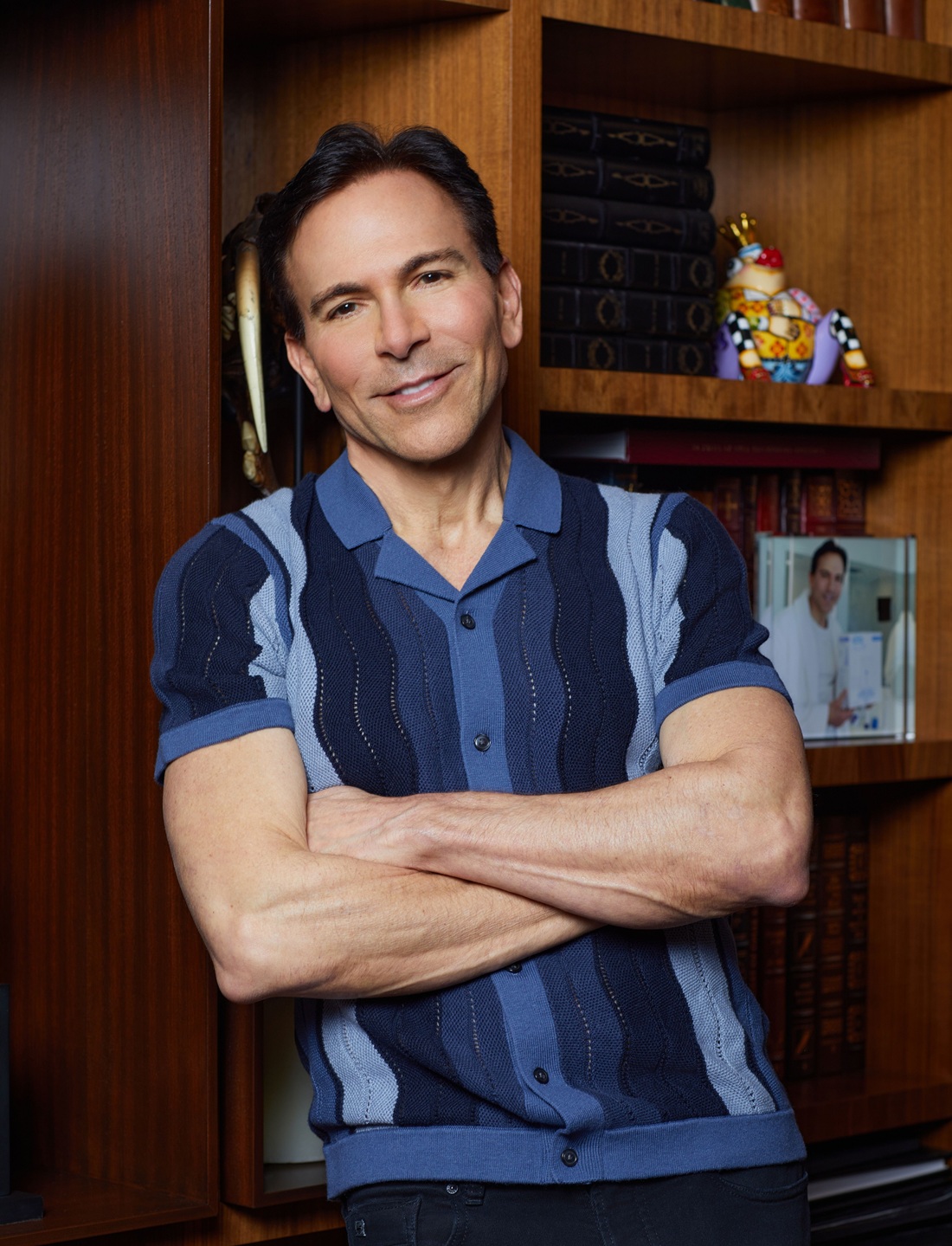

BY LAURA SCHREFFLER

PHOTOGRAPHY NICK GARCIA

GROOMING ANA RIVERA

SHOT ON LOCATION IN ORLANDO, FL

JEWELRY: David Yurman

JACKET & SHOES: Francisco’s own

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

Right now, at this exact moment in time, Francisco Lindor is a happy man. There is nothing about his life he would change. And how many freaking people in the world can say that?

It’s the offseason, and the New York Mets shortstop is at home in Orlando, getting a haircut and preparing to throw one of his legendary New Year’s Eve parties for friends and family, as he does every year. His Zoom video is off, but he briefly flickers the camera on to show that he is currently swathed in a barber cape. His daughter, 2-year-old Kalina, is by his side, consumed by her crayons. He looks blissed out, and says as much. “I’m at home, with my daughter, getting a haircut and loving my life. I’m living the dream.”

Seriously, the man is good. Sorry, he’s great. He’s surrounded by his extended family from Puerto Rico, many of whom are in town for the holidays (outside of his mother and sister, who live across the street, and father, who resides nearby), and he’s just celebrated a year of marriage to wife Katia. When you’re this content, New Year’s resolutions aren’t strictly necessary.

“I try to live life the same,” the 29-year-old athlete explains. “I don’t try to change much. Like, I don’t think, It’s a new year, so I have to try this now. No. For me, it’s life, and I try to keep my life as consistent as possible. My goals vary throughout the months, weeks, and days. I don’t go, Oh, it’s 2023. I want to own a home or start a business. I don’t play that way.”

There is one exception, and for Lindor, one of the most exciting players in Major League Baseball, that exception is, of course, baseball. With that, he very much does play that way. “Every year I have new goals, and I would call them resolutions, but to me, it’s not that important or urgent to create a resolution on New Year’s Day. If it gets done, it gets done at the appropriate time.”

Given how great a 2022 season he had (outside of, perhaps, the month of June, when he put up a 78 wRC+ while playing with a fractured finger), Lindor is setting the bar high for his third season with the Mets. After all, he largely contributed to the team’s success last season, which was one of the best regular seasons in the franchise’s history, with incredible defense and overall consistency. His incredible stats — his 6.8 fWAR and 127 wRC+ and 26 home runs (more than any other Mets shortstop in history) — speak for themselves. Many consider his overall ninth finish in National League MVP voting highway robbery.

His haircut is now over; his camera is officially back on, and he’s also back to speaking about said goals. “I go back and forth between how I did the previous year, what I want to accomplish the following year, and what I think is actually realistic. A lot of players will say, ‘I’m going to hit 50 home runs this year.’ But I don’t think you’ve got 50 in you, sorry. You have to create goals that are somewhat realistic in the baseball world,” he says, noting that currently, he’s not even sure what his goals look like. “I just started working out — hitting, actually — but I just started training again, doing basic activities. Usually my goals come as the offseason progresses, when I go back through my notes of how I did the previous year. I have a lot of thoughts that I write down throughout the year, and I use them to create my approach for my goals in the year to come.”

When his junior year with the Mets kicks off on March 30 in Miami against the Marlins, he says he’ll have worked on literally everything he possibly can to make his game that much greater. “I try to work on building, hitting, running — everything I can to get better each year. I don’t let how good I did one year affect me to the point that I can say, ‘I’m done working on that.’ The moment I stop working on something, it suffers. I’m a big believer that God gave me the ability to have talent, but I have worked hard on my craft. Am I going to be perfect? No, but I strive to be.”

That said, his priorities have slightly shifted since becoming a husband and father. Kalina is not only on his lap now but is a frequent fixture there before and after games. Being a dedicated, doting dad certainly hasn’t detracted from his game any (see aforementioned stats for proof), but it has resulted in scheduling tweaks to optimize both his on-field performance and his time at home.

“Before my family — my wife and my daughter — baseball was probably 85% of my life. Now, it has shifted a little bit,” he admits. In Orlando, that means sinking some serious finances into his at-home health, inclusive of a home gym with every kind of recovery machine under the sun and a daily visit from an at-home masseuse.

JEWELRY: David Yurman

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

“I think the most important thing for an athlete is not how hard you work, but how you work, how — specific for your body and for your position — you work,” he notes. “I can’t go out and work out like a football player. Take Tom Brady, for example. He’s one of the greatest athletes the world has ever seen, but he can’t really go and play shortstop, just like I can’t go and play quarterback. Football players train heavier and get bigger, stronger. Basketball players train faster. I can’t work out like they do, no matter how we try to compare to one another. But I do know I can learn from them. I love watching other athletes perform at the highest level. Maybe I don’t understand the sport or what it takes to be successful in the sport, but I love to study how they go about it. At the end of the day, you’ve got to have a certain mindset to be successful, in anything that you do.”

For Lindor, success means strategically merging his home and work lives. He used to be a night owl who would work out until the wee hours of the morning. Now, in a bid to be there for his daughter, he’s on the field at 6:30 a.m. and home by 2 p.m. at the latest. He’s truly got it all figured out.

But when something is important, that’s what you do. And while it’s a given that his family is important, being a Met means everything to him, too. In fact, the first thing I noticed when his video returned post-fade was the thick gold Mets chain around his neck, winking at me in the evening lamplight. To Lindor, it is more than just a team emblem: it is a symbol of his success.

“I’m super proud to be a New York Met,” he admits when I reference his one accessory. “I mean, I was proud and I’m still proud that I was a Cleveland Indian, and I have the utmost respect and love for that organization. They groomed me; they did everything right with me, and I gave everything I had in the moment to them — to the organization, to the fans, to my teammates, to everyone. But once I became a New York Met, I knew we were going to do very special things together. Typically, I wouldn’t wear team hats. Now I wear a Mets hat all the time, and I also wear the chain.”

He’s prouder of his work with this team, his second since being selected by the Indians (now the Cleveland Guardians) in the first round of the 2011 MLB draft with the eighth overall pick. And though he blossomed and became the All-Star player he is today during his tenure with his former team after making his MLB debut in 2015, they were unable to keep him financially, hence the trade.

Lindor’s rationale for preferring his current position makes total sense. “It’s because I’m secure here,” he admits. “Like I said, I have the utmost respect, but it was year-to-year contracts there, as opposed to here. I signed the contract with the Mets for 10 years. [A more in-depth look at said contract: 10 years at $341 million, inclusive of a $21 million signing bonus, $341 million guaranteed — the third largest in MLB history at that time — and an annual average salary of $34.1 million. This year, Lindor will earn a base salary of $32 million, while carrying a total salary of $34.1 million. Yeah, it’s high.] Can they trade me? I’m sure they can, but in my mind, I have security. No matter what it is that makes you feel secure, that’s always the best. In a relationship, when you go from just talking to dating to being engaged to marriage, your relationship just continues to grow. It’s the same thing with the Mets. I signed this long-term commitment; I feel secure, and I’m ready to give everything I’ve got to the organization and my Mets family.”

In his mind, that means one thing most of all. “What we’re going to do is win. We’re going to find a way. There’s nothing else; there’s no more trying to get to know each other. It’s time. It’s time to win the World Series and to be the best shortstop I can be.”

But he isn’t going to rush it. Everything will happen as it should, in due time. “You’ve got to do things correctly; you’ve got to play the game the right way,” he says. “You’ve got to respect everything around you, and only then will things start to happen.”

“Respect” must be Lindor’s middle name. (Just kidding, it’s actually Miguel.) It happens to be one of the reasons he uses No. 12 — it’s a sign of respect for his hero Roberto Alomar, who is widely regarded as one of the greatest second basemen of all time. He also cites Barry Larkin and Derek Jeter among his inspirations, but notes, “There are so many different baseball players that I have idolized, whose games I’ve respected. However, it is very tough for me to try to be like them. I imitated them, sure, but I always wanted to be me. I always try to be myself.”

And bless him, Francisco Lindor is that rare unicorn of a human that is, quite simply, happy being exactly who he is.

SHIRT: Brain Dead

JEWELRY: David Yurman

SHOES: Francisco’s own

AUTO: Lucid

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

Francisco Miguel Lindor Serrano was just 12 years old when he moved from Caguas, Puerto Rico, to the United States. At the time, he could not speak a word of English. But as he prepared for his first day of school in America, his father devised a plan.

On his way to the Montverde Academy in Montverde, Florida — a private school whose baseball facility was eventually named in Francisco’s honor in 2013 — Miguel Angel Lindor was attempting to teach his son one very important phrase. “My dad kept saying, ‘Just tell people, ‘I don’t understand,’ and if they don’t get it, move on to the next person.’ But I couldn’t memorize the damn phrase, so he wrote it on my hand. And every time anyone spoke to me that first day, I just showed them my hand. And then, eventually, I started learning English, thank God.”

Luckily, people were kind — Montverde is an international school with students representing more than 100 countries — but it still took the young Lindor a disproportionally long amount of time to learn the new language. He wanted to look cool, and as a preteen, there is nothing less cool than showing weakness.

“It took me about a year and a half to learn English,” he admits hesitantly. “The reason why is because I was always trying to be a cool kid. That was my coping mechanism, acting like I didn’t care. If you tried to make fun of my English, I was like, Ah, I don’t need it anyway. I’m Spanish, I’ll be fine. I’ll play baseball and that’s it. I was in the ESL — English as a second language — program, and everyone that was in my program moved up to ESL 2 for the second semester, but I failed it and I was held back. And that’s when I was like, Oh, hold up. I’ve got to take this serious. I need English. I’ve got to pass my classes. This is not cool anymore; I’m the only one sitting in this classroom. This is actually very embarrassing. From then on, I promised that I would pay more attention.”

But it was lonely living in a world where he was struggling to speak the language, away from his friends and most of his family; his mother and siblings would not join him in the States for another six years, until he signed with the Cleveland Indians.

“It was challenging,” he recalls now. “I called my mom many nights crying, not understanding what was happening. It was tough to sit in a classroom and have someone talk to me for 45 minutes and not understand a word of what was said. You can tell me whatever you want, but if you don’t say, ‘Hola,’ I’m not understanding it. But my classes were fairly easy. One of my teachers spoke Spanish, and another one spoke different languages — she was from the Netherlands — so I was able to communicate with them, but they tried to teach their classes in English, to force you to learn the language.” And it worked, though it was a struggle. Lindor faked it until he made it, and when he finally did get a grasp on the English language, he realized — thankfully — that he loved it. “I wouldn’t change a thing about my childhood,” he declares.

Interestingly, even though it was lonely on his road to learning the language, Lindor tells me that he’s happiest when he’s all by himself — even if he’s doing absolutely nothing — sitting in silence. And not to go all Psych 101 here, I have to wonder if it’s because he struggled so hard to make sense of the noise. He simply thinks it’s because he’s a lone wolf.

SUIT & SHIRT: Ralph Lauren

JEWELRY: David Yurman

SHOES: His own

ON KATIA:

DRESS: Jonathan Simkhai

SHOES: Her own

ON KALINA:

OUTFIT: Her own

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

“I would say that I’m more of a lonely soul,” he divulges. “I ride my bicycle — that’s my hobby — for three or four hours, and I’m fully charged for the day. And I haven’t done this in a while, but in the past, during spring training I’d go to the movie theaters by myself. I can go to a bar by myself; I can go to eat by myself, go to a restaurant by myself. I can be on the couch all day by myself, and I’ll have zero regrets.”

Even when he’s on the couch with someone else — including wife Katia — silence, to him, is truly golden. “Just sitting on the couch with my wife is quality time. We can be right next to each other, watching a dumbass show, and that’s quality time. Her quality time looks different, but I have learned to be able to communicate and say, ‘Hey, I need, I need some time, some quiet time, all to myself.’ And she understands.”

Obviously, Lindor is a good dude. He dotes on his daughter, who infrequently strays from his knee during our chat (and who is a frequent fixture on his lap even during press conferences), and clearly loves his family. He seems much too wise to be 29, especially when he discusses interpersonal communication and love languages. I mean, how many men in their 20s even know what love languages are, never mind how to master them? I’m impressed.

“My wife and I have been together for four years; I’m learning her ways, and she’s still learning mine,” he concedes. “It’s a fairly new relationship, but we try to grow every day. And from what I’ve seen, I’ve learned that we definitely need to put work into growing together, because if we start to grow in different ways, that’s a problem.”

“You, sir, are very young to be this evolved,” I tell him, like the wise, old owl I am.

“Thank you,” he responds. “I ask questions. I try to understand, and my wife has taught me to listen to her. With Katia, I have learned to try to communicate a little better. I have also actually taken a test about love languages already.” He giggles. “Actually, she says that men close their frontal lobes after 28 or 29 years old. And now that I’m 29, I guess I’m fully developed.”

I tell him not to bank on it, but I’m joking — like I said, I’m impressed by his maturity. And also by his kindness, generosity, and pretty much everything else one can be impressed by. Lindor is a good person — and has been recognized for it, too. In 2022, he accepted the Marvin Miller Man of the Year award, an annual accolade given to a player as voted on by his peers ‘whose leadership most inspires others to higher levels of achievement,’ according to the Major League Baseball Players Association. (This award was named for the association’s first full-time executive director.)

I ask him to vocalize why he thought he had been honored. It isn’t the easiest of questions to answer, but Lindor responds articulately and gracefully. “I try to represent not just my last name or my organization, but to reach every Latino, every black and every white player. I try not to run from everything. I’m a fighter. I’m against zero owners. They want something, we want something, but at the end of the day, we want to make the game better. The game was extremely fun and good when I walked into it, and I want to leave it even better. I think of all the future generations, too. Most of us get into the game because we love it, and we continue to pursue it because we think that we can find a way of helping our families or helping ourselves.”

Speaking of helping families, guess what Lindor did with his first major paycheck (procured after being drafted)? I’ll tell you: he bought houses for both his parents — while he himself acquired a used car.

“I wanted to help my parents come out from something and put them in a much better situation. I was lucky enough, blessed enough, to be able to get them each a home. It was one of the happiest moments of my life to be able to provide something for them — two people who worked so hard their entire life to make sure my siblings and I had something to eat on a daily basis. To be able to provide for them in that moment was great.”

Bless his heart, right? But don’t feel too bad. That used car was a 2009 Mercedes-Benz SUV, followed by a used Range Rover. (In case you were wondering, his first brand-new vehicle was a 2014 stick shift Shelby Cobra that he literally didn’t know how to drive that he bought to create his credit line, as he had previously been buying things for his family with cash.) Now, he has seven hot wheels in his collection, but then, he also has that mega $341 million contract under his belt. And Lord only knows how many cars that amount of money could buy.

As Lindor’s paycheck grew, so did his luxury tastes. “As I got older, signed higher contracts, and became wealthier, I was able to get myself nicer things. But the most important thing then was to take care of my family, and to this day, it’s still the most important thing,” he declares.

That said, luxuries — even the little ones — are essential. Not just as signs that he’s “made it,” but because luxury truly brings him joy. “Luxury means different things to different people; everything is relative,” he notes. “For me, luxury is eating well at great restaurants, having a masseuse, owning great cars. Luxury is the ability to get yourself things that bring you joy, and for me, joy can be found in getting a nice stroller for my daughter, watching a nice TV when I’m sitting by myself on the couch, having a personal chef. I have a nice weight room at my house. I don’t have to leave my house to work out — that is a luxury. Being able to take my daughter to Disney World — even though I don’t like theme parks — that is a luxury, too.”

But when it comes to watches, well, that’s a different story. To Lindor, watches are far more meaningful than a simple luxury. And what’s more, they bring him a sense of peace that nothing else in life — not even alone time on his bicycle or on the couch — can match.

“I could have a thousand watches, and for someone else that might be a dumb expense. For me, it’s art. It brings me a lot of joy and a lot of peace looking at my items. For me, a watch used to symbolize success, but not anymore. I have so many in my collection that it doesn’t symbolize that for me anymore.”

He has so many that he can’t quite share a number, but rest assured, it’s a lot. He wears one constantly. One before he showers, another during the day, a third before bed. Yes, he wears his watches to bed, and no, they’re not uncomfortable. He also wears his chains, rings, and all manner of jewelry under the covers; he’s counting sheep fully blinged out.

Again, I won’t attempt Psych 101 here, but the reasoning seems obvious when he explains how he was raised. “My passion for jewelry started at Christmas while I was growing up. We didn’t have much money, but each Christmas, there was one thing Santa Claus would bring us. One year, [I wanted an] electric scooter, but it was expensive. I put it on my wish list, but I didn’t get it. I ended up getting a little box; it was square and long. Inside was a gold Cuban chain with a baseball player on it. And in that moment, I remember being mad, being upset because I didn’t get that good Christmas gift that every kid was going to get on my block. But year after year, I always had [that chain] on. I played with it on. I slept with it on. I guess maybe that’s where everything started. I used to walk around in old San Juan and go to different jewelry stores while my mom was at work. I would window shop because I couldn’t afford anything, to the point where owners would tell me to come inside. They’d show me TechnoMarines, Casios, Fossils. So wearing a watch to bed now doesn’t make me feel uncomfortable: it makes me feel at home.”

Currently, he’s wearing a Patek Philippe — which is in a completely different league than those Casios of yesteryear — and a smile, which, as it turns out, is the most important thing to be wearing of all. (Sorry, I’m cheesy, but “Mr. Smile” is his nickname — procured while playing for the Indians.)

Is he always smiling? Well, no, he admits, “But I do believe a smile can change someone’s life, including your own. If you’re having a bad day, look at yourself in the mirror. If you smile and continue to try to smile, your day will change — I truly believe that. I think we don’t smile enough; we’re not kind enough to others. Smiling is a way of bringing joy to someone else’s life. The person you’re talking to, they mimic what you’re doing. You smile, I smile. You get mad, I get mad. I nod, you nod. We mimic each other. If you smile and that person smiles, you might turn their day around. I love that. You have the opportunity and the power to change someone’s day.”

Marvin Miller would definitely be proud.

SUIT & SHIRT: Ralph Lauren

JEWELRY: David Yurman

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia