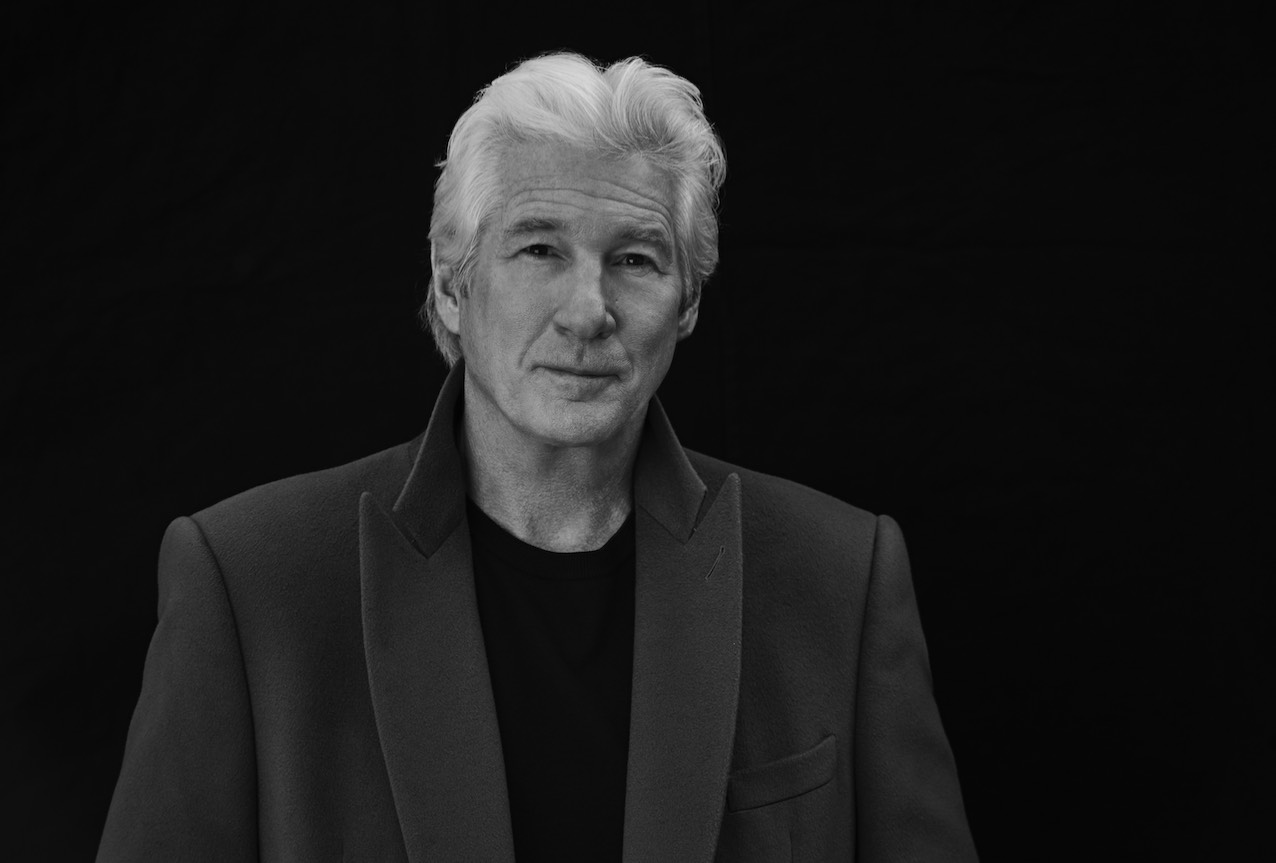

Richard Gere on Settling for a ‘Happier’ Ever After Ending

Photo Credit: All Photos by Mark Squires

Richard Gere is messing with our fantasy life, and not in the way you might think.

We’re chatting amicably about ambiguous movie endings when he suddenly goes rogue and starts playing fast and loose with another idea for one of our favorite—and one of his most iconic—films, Pretty Woman. He presents us with an alternative universe where his wealthy businessman, Edward Lewis, might not give Vivian Ward, the hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold, her happy ending.

“You don’t know exactly what’s going to happen with them,” he says. “They’re having a good ride right now, but who knows what’s going to happen a few months down the road.”

When we express displeasure on the behalf of females everywhere (Pretty Woman doesn’t hold the record for highest domestic cinema ticket sales for nothing), Gere is pragmatic: “That’s fine,” he says steadily, “But in my own experience, life is not quite like that.”

A predisposition to an imperfect ending might be one of the reasons Gere has directed his career in recent years towards more thoughtful, character-driven fare that explores the human condition. His two upcoming releases are radically different, yet there is a common thread of sadness that weaves through both, tethering them.

In Israeli director Joseph Cedar’s English language debut, Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer (in theaters April 14), Gere plays busybody ‘connector’ Norman Oppenheimer, a guy whose neediness is on par with his propensity to lie pathologically. He knows everyone, though no one seems to know anything truly significant about him. He’s a yenta who, almost desperately, tries to please and accommodate strangers because such is his need to be liked and accepted. He is a lonely, sad guy; a would-be operator always dreaming up financial schemes that never quite come to fruition; a full-time networker who seems to have no real friends and annoys almost everyone he meets.

But Norman’s dire situation changes when a calculated act of kindness towards an extremely charismatic Israeli politician (played by Lior Ashkenazi), alone in New York during a low point in his career, pays off. Micha Eshel becomes the Israeli Prime Minister, makes Norman a trusted confidant, and offers him the respect and attention he’s always craved. Flush with his newfound feeling of success, the fixer attempts to use Eshel’s name to leverage his biggest deal ever: a series of quid pro quo transactions linking the prime minister to Norman’s nephew (Michael Sheen), a rabbi (Steve Buscemi), a mogul (Harris Yulin), his assistant (Dan Stevens) and a treasury official from the Ivory Coast. Needless to say, Norman’s wheeling and dealing will only end in disaster.

It’s an interesting role for Gere to take on, and one that renders him almost unrecognizable, his real-life confidence and serenity hidden behind a newsboy cap and engulfing winter coat. But then, he likes a challenge and exploring the unfamiliar. “[The director] is an Israeli Jew, and I think he needed for me to understand the thousands of years of history that went into a character like this. We started very slowly and intuitively [figuring out] what Norman is.”

It took a lot of analyzing and deconstructing to get there, but he says it was a welcome challenge. “Norman is an odd character. I had a lot of questions about him: ‘What is his backstory?’ ‘What is his sexuality?’ ‘What is the animal side of him?’ ‘Does he get angry?’ ‘How thick or thin-skinned is he?’ ‘How genuinely does he want to help, and how is that connected to his psychology?’ Everything he says is a lie, to some degree.”

And while Norman is more than a little pathetic, Gere couldn’t resist the idea that he was also, inherently, good. “He genuinely wants to help. He wants to belong. He’s a Jewish guy [who] not only speaks for himself, but speaks for his culture.”

Gere continues, “I didn’t find any anger in him. He’s not a user, which you’ll realize when you see [the end of the movie]. Everyone else gets what they want, realizes their dreams. In the end, Norman delivers that to everybody.”

His character in The Orchard’s upcoming May 5 release, The Dinner, is Norman’s polar opposite. Gere plays a charismatic politician, a man who is larger-than-life—he commands respect and authority simply by stepping into a room.

The film is a dark psychological thriller based on Dutch author Herman Koch’s 2009 novel of the same name, though it is intentionally not a faithful adaptation. Writer Oren Moverman, who took over the directorial reins when Cate Blanchett dropped out, told the actor not to bother reading the book because the screenplay went in a completely different direction.

For starters, the setting shifted from Amsterdam to New York. Dutch candidate Serge Lohman morphed into congressman and governor hopeful Stan Lohman. For those familiar with Koch’s novel, although the ending differs, the plot is still the same: two couples meet for dinner at a swanky restaurant, where every course is edible art, every presentation a dance. The men—Stan (played by Gere) and Paul (Steve Coogan)—are estranged brothers. It is not, as you might expect, an average night on the town. The narrative is set up by courses—from apéritif and digestive to dinner and dessert—where viewers learn, through a series of flashbacks and interruptions, that the twosome and their wives are anxiously discussing what to do after their teenage sons commit a horrific crime that may not only send them to jail, but could also jeopardize any hopes Stan has for his political career.

With each course and every scene, another layer of sadness, desperation, trauma and regret is revealed. Relationships ultimately shatter, and all four characters are left trying to put the pieces back together. It’s a parable on the sometimes savage reality hidden beneath the surface of average, seemingly-stable, middle-class families, and raises the question: how far would you be willing to go to protect someone you love?

Despite being a politician, Stan is the one redeeming character in the film, which also stars Rebecca Hall and Laura Linney. “I thought it was important that, given all of his issues, he [displays] a large sense of moral discipline and basic goodness. He has to sacrifice his most loved persons in the service of a greater sense of responsibility; it is the opposite side of selfishness.”

We won’t give away the ending—nor could we, because it’s one of those ambiguous, unfinished affairs, a small step away from the maddening, unanswered spinning top of Inception—but we can say that it’s shocking, dark and more than a little confusing. “Everything is kind of up in the air,” Gere agrees. “We know a few things. We get the sense that life moves on somehow. As to what exactly the ending is, that’s up to you.”

ACT II

Spend five minutes talking to the guy, and you’ll be asking yourself some pretty esoteric questions. ‘What is the self?’ ‘Is there life after death?’ ‘Does Zack Mayo wind up with Paula Pokrifki in An Officer and a Gentleman, or does he just carry her off and leave?’ (Thanks for making us question that one, Richard.)

If you haven’t studied up on Gere, you might wonder if he was a philosophy student. (He actually was, but he originally attended the University of Massachusetts Amherst on a gymnastics scholarship.) A predilection for deep thought eventually led him to Buddhism, which he’s been practicing since his mid-20s, first studying Zen Buddhism before traveling to India in 1978, where a meeting with the 14th Dalai Lama nudged him towards Tibetan Buddhism. This school of thought is characterized by many things—one of which is a belief that the mundane world is inseparable from enlightenment. Buddhism, in general, is a cultivation of wisdom, kindness and compassion.

Gere does not simply pay lip service to spirituality; he’s a devotee. He cofounded Tibet House, which advocates for human rights in Tibet, as well as The Gere Foundation, which aims to alleviate suffering and help restore autonomy to the Tibetan people. For the last two decades, he has served as Chairman of the Board of Directors for the International Campaign for Tibet and has received numerous humanitarian awards acknowledging his commitment to human and civil rights, health and education. Most recently, the actor flew to Bodh Gaya to hear the teachings of the Dalai Lama, who continues to be a close and personal friend of the actor’s.

We suggest that Gere, who professes himself to be an eternal student of Buddhism, must also enjoy exploring other religions, given that the subject matter of Norman is so heavily intertwined with Judaism and his upcoming third film of the year, Three Christs—slated for a fall release—also seems like it would revolve around religion (the adaptation of Milton Rokeach’s The Three Christs of Ypsilanti is a true story about the psychiatric case study of a Michigan doctor treating three paranoid schizophrenics who all believe they are Jesus).

But he sets us straight: “Three Christs is really about the enigma of the mind. In a way, it’s closer to [how] a Buddhist would explore the mind; it’s not going to be about Christianity.”

This appears to segue easily for him into an explanation of his own beliefs. “In exploring any kind of spirituality, it seems [we] have to go the route of exploring the mind and how we function. [You can minimize problems] through meditative practice, through contemplation, through learning about the nature of the self and the nature of reality, by exploring pure emotions of love and compassion and altruism. I have no sense that I have achieved any of this stuff, but I can certainly say I’ve been working at it for a long time and it does create a vaster sense of well-being, for sure.”

His faith is something Gere is certainly going to need in the coming years, given the current state of our country. As he puts it, “This is one of the darkest moments I’ve ever seen. It’s a high state of anxiety everywhere, and the reality is that everything is changing.”

But he does believe that the circumstances will improve. “However dark it is, or however dark you’re perceiving it to be, [in] the next moment, it’s not going to be there. The cause is a moving target; the effect is a moving target. Everything is moving constantly and this too shall pass,” he notes, before addressing the elephant in the room: “There will be a moment when Donald Trump is not President of the United States.”

ACT III

If you love a good romance, Richard Gere was probably featured in some of your favorite swoon-worthy on-screen moments. His earlier work cemented his status as one of Hollywood’s most iconic romantic heroes and anti-heroes in films like An Officer and a Gentleman, Days of Heaven, American Gigolo, First Knight, Looking For Mr. Goodbar, Shall We Dance and, of course, Pretty Woman. Being crowned People’s ‘Sexiest Man Alive’ in 1999 didn’t hurt either.

He has been working consistently since 1975’s Report to the Commissioner, sometimes averaging as many as three films per year. Yet Gere has surprised many fans with some of his career choices, shrugging off the romantic hero cloak quite artfully to opt instead for character-driven roles.

The transformation from film star to thespian was intentional, he says. “When I was much younger, I set out to find something specific, but it never quite worked out that way. Now, if I’m just open to whatever is good, whatever has value and—probably, more importantly—whatever touches me in some way, I’m continuously happy.”

Although not classically trained as an actor, Gere moved to Cape Cod to work at a repertory theater after dropping out of college two years in. His first major role was in the original London stage version of Grease in 1973; Hollywood beckoned shortly afterward.

He has since won a plethora of awards, including a Screen Actors Guild (SAG) trophy and a Golden Globe for his work in Rob Marshall’s Chicago. And while he loved making the 2003 musical crime comedy, Gere explains he only takes projects now in which he’s truly invested—which, in recent years, have included The Second Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, The Benefactor, Arbitrage, Brooklyn’s Finest, Lasse Hallström’s critically praised The Hoax, and as one of seven Bob Dylans in Todd Haines’ I’m Not There.

“I’ve never done anything that’s just for the money—ever. There were times that I certainly did things that weren’t the greatest projects in the world, but by the time we did rewrites… I could see how they would be of value.”

He adds, “You can’t always control how you execute something. There are too many parts, too many people, too many decisions that could go one way or another. There is no guarantee. Even if you have the best script, the best director, the best actors, the best everything, there’s no guarantee that it’s going to turn out well.”

Since he’s more interested now in making stories about people, Gere is aware that he’s limited. Big-budget productions are more stylized, more about special effects, glitz and glamour, and Gere is more than happy to be involved in the indie community. And not just because of the character-driven content—he’s more efficient in this space. He works hard, and he works smart. He sees no reason to waste time, and appreciates the quick shoots that also accompany independent films.

“Time Out of Mind, we shot in 21 days. The Dinner was 28 days. Norman might have been about 30 days, which is half of what [shooting a film would have been] in the old days. I’m okay with that. I like when things move fast. I like everyone being on their feet, thinking fast, kicking at a high, creative pitch all day. I far prefer that, actually. The films that I’ve been doing now, the last five or six that I’ve made, have all been in this small arena, quite personal and really focused on characters, on the minutiae, on thought process and emotions. I’m really liking this run I’m on now.”

ACT IV

Richard Gere is the kind of guy who prefers to think about the theory of everything, as opposed to the end of everything. That said, he believes most aspects of life have an expiration date—including his career.

Although he shows no sign of slowing down after 40 years in show business, he says retirement isn’t out of the cards. “I’m amazed that there are still so many things that I want to do, and that people are asking me to do, frankly. I don’t know how long this is going to last.”

When we ask him if a) it would be hard to take a step back from making films and b) if filmmaking is his top priority, his answer is surprising: “I don’t think [making films] ever was, to be honest. It’s a great job, and I can’t imagine another job that I would like nearly as much. I’m humbled by it, that I’ve been allowed to do this my whole life, since I was 19. It’s putting kids through school. I have health care for everyone in my world, I can pay my bills and I can have fun being very creative and adventurous. So it’s certainly a great job. But my real job is my family, my friends, working with my mind.”

Gere has never really withdrawn from the silver screen, but he assures us he will simply take the time to explore other passions when that time comes—for example, at his Bedford Post Inn (located in the affluent hamlet of Bedford, New York), where you might find him doing yoga on any given day in the on-site studio.

“At some point, I’m not going to feel like a 36-year-old, but not any day soon. I feel like there [are] still enormous possibilities.” He pauses before adding, “I can look rationally at my life and go, ‘Twenty [or] thirty years [from now, that] is going to be about it.’..I’m perfectly fine with that.”

It might help that he doesn’t truly believe in endings: “My body ends for sure, but my mind doesn’t end. The voyage doesn’t end. The explorations don’t end. I’m not saying everything ends. You trade in one car for another, but you’re still moving.”

Now in his mid-60s, he’s learned how to keep going after experiencing his personal share of strife. He was married to supermodel Cindy Crawford from 1991 to 1995 and former Bond girl Carey Lowell from 2002 to 2013―with whom he has a son, Homer James Jigme Gere, named after his and Lowell’s fathers combined with the Tibetan name meaning ‘fearless’. Since then, Gere has found love again with Spanish socialite Alejandra Silva (the couple, who met at a charity event, have been dating for nearly two years).

He knows he hasn’t been perfect, but that’s life—and he wouldn’t change the past. “That doesn’t mean I haven’t messed up and done horrible things, but [I don’t have] regret in that sense of debilitating guilt. I acknowledge the things I’ve done that weren’t great. I hate that people have gotten hurt in any way—that I regret. There [are] none of us who have ever escaped that. You learn from it, you become better for it, you move on and you grow.”

Gere doesn’t believe in the fairytale, he tells us. No white knight, no magic castles. “In my own experience, life is not like that. I’m not saying that to be [negative]; it’s just more realistic. [I don’t feel] there’s ever a place where one gets to [thinking] ‘I’ve done it, I’m happy now.’ I think that’s completely unrealistic.”

Instead, he says, “As a 67-year-old, ‘happier’ sounds much more realistic to me. I’d settle for ‘happier’. A happier ending, happier ever after. That’s good enough.”