Gridiron Great Jim Brown Speaks About His Path to Success

PHOTO: TAJ STANSBERRY

“I’d rather be a free man in my grave than to live as a puppet or a slave.”

Those lyrics from reggae great Jimmy Cliff’s 1972 song, “The Harder They Come,” have stuck with NFL legend Jim Brown over the decades.

“I always really liked reggae,” the ex-gridiron great says, “because [the] music was always about something—I mean about pretty girls and all that too—but it was always about something. [Bob] Marley was a revolutionary, and so was Jimmy Cliff. Those guys had a greater consciousness than the entertainers in this country, and they were making music to that consciousness. I was right up in there, one way or the other, because of the kind of life that I lived.”

Life that I lived. Those four words hang in the air like the clouds of dust Brown routinely left in his wake when he dominated at fullback for the Cleveland Browns from 1957 to 1965. As the (gulp!) 80th birthday of the controversial yet compelling man approaches on February 17, Brown—considered by many to be the greatest running back who’s ever played on the gridiron—ruminates over his life not just as the athlete, actor and activist who continues to champion economic and political equality for African Americans, but also on how aging has influenced his evolution. We sat down with Brown in Southern California, where he’s lived since 1966 when he shocked the sports world by walking away from pro football at the top of his game for a full-time acting career on Hollywood’s big screen. More than 35 film credits later, he moves a lot slower, needs help getting up from a couch and doesn’t stand 6-foot-2 like he once did. There are touches of grey in his eyebrows but his signature thick black mustache is still intact—as is the charisma he exuded decades ago.

In his rich baritone voice that complemented his chiseled body well during his sex symbol days−he was featured in Playgirl in September 1974−he reveals what pleases him most about himself at this stage in his life.

“I think that I’m most proud of the adjustments that I have made in my life to be a better person,” he says, pausing before adding, “the ability to give something a second thought—and even if I’m being done wrong—to not retaliate or be dragged into negativism. That was difficult for me because I was on a ‘right and wrong trip.’ And there was a whole lot of wrong that people were doing so I would have been fighting all my life to beat up people, beat them down.” He breaks into a laugh, only to be interrupted when his two youngest children— son, Aris, 14, and daughter Morgan, 12—arrive from school for the photoshoot (Brown has six adult children from previous relationships). “How you doing pretty girl?” he asks Morgan, a miniature version of her beautiful mother, Monique, Brown’s wife of nearly 20 years—and 38 years his junior. “I’ve got to get a hug.” When his kids leave the room, Brown picks up where he left off. “I’m proud to be able to have adjusted my way of thinking so that I could be more forgiving, more intelligent, not to fall into the trap of negativism and to be able to fight for the right thing without bitterness.”

Asked what he attributes the change to, he replies, “Well, a lot of times it got me in trouble. The few physical fights that I’ve had, I could have avoided those things very easily if, at that time, I understood what I had later learned to incorporate into my life. It’s probably the only thing that I would say I’m proud of because I don’t live in a way of being proud of the things I’ve done and all that kind of stuff. But, that’s a step in my life that’s between me and me. I had to figure out that what I knew the truth to be is way more important than somebody else telling a lie or someone else defining me when I can define myself and having me react to the instead of—”

PHOTO: TAJ STANSBERRY

He stops in mid-sentence when Monique walks through the front door. “Hey babe,” he says to her, his face lighting up.

She admires him in his Brooks Brothers suit—a step up from the sweat suit she last saw him wearing when he left home a couple of hours ago—flashes a big smile and says, “You look nice.”

When she heads into another room, Brown resumes once again.

“It has to do with me and my analysis of myself. Right and wrong isn’t always right and wrong. That’s a crazy statement, but it’s a true statement. You can be in the right and be wrong as hell because if you take advantage of somebody’s weakness—even though you have the right to do it—it isn’t a good thing to do, to dominate a person unfairly but within the rules. There are a lot of things that, if you grow and you observe life and you start understanding what life is about, then there are things that you don’t do to other people.”

As an example of the growth he’s made, he tells how he is now able to deal with guys whom he previously couldn’t. One man, whom Brown says “kicked me to the curb” 20 years ago, had been at his house the previous evening to help with Amer-I-Can, a national program and movement created by the NFL great in 1988 to empower individuals to take charge of their lives and achieve their full potential. Rather than avoid the man, who has been incarcerated like many of the people Brown has helped throughout his lifetime, the activist was open to listening to his visitor—and greatly rewarded by doing so upon finding out how much the former inmate had grown. Now, Brown can barely remember what his one-time enemy used to do that irked him. This has nothing to do with the septuagenarian’s age. He’s progressed as a human being.

“That’s something about myself that I feel good about—and particularly at the age that I’m at it would be terrible,” he says, breaking to laugh, “to be a person that’s holding grudges and passing judgment on everything that’s moving. That would be a miserable circumstance. I’m glad I’m free. My freedom comes because I can respect others and their rights—and even when it doesn’t appeal to me, I can still take a look at it and then allow them to have their opinion.”

As much as Brown touts his growth, his alluded dark past is well documented and well known. Accusations of violence against women have plagued him in the past—even though he was never found guilty in those cases. In 2002, after being found guilty of misdemeanor vandalism arising out of a domestic dispute with his wife, he opted for jail instead of accepting the terms of his probation.

PHOTO: TAJ STANSBERRY

Years ago, Brown’s combative history often overshadowed his good deeds. When he played for the Browns, he founded the Negro Industrial Economic Union, which later became the Black Economic Union, to promote economic development in African-American communities. In hopes of quelling the gang violence in Southern California, it wasn’t unusual for him to host 400 members from rival gangs in his Hollywood Hills home on a regular basis to teach and them about self-pride and personal responsibility as part of his Amer-I-Can Foundation. He’s always preached education, which he calls a weapon.

Ironically, Brown is a good friend with another well-known sports figure known for his temper. Bobby Knight, Indiana University’s legendary ex-basketball coach, is as famous for leading his Hoosiers to three national championships as he is infamous for slinging a chair across the court during a game in 1985. When the former football star talks about the coach being misunderstood, one wonders if Brown is talking about himself.

“Sometimes people don’t know the depth of these volatile individuals. To me, he’s one of the most gentle people I know,” Brown shares about Knight. “See, a lot of these volatile screamers and chair throwers and all that stuff, underneath they really have the best interest in people. Well, why would he throw a chair? Well, because he’s human, and he threw a chair. That’s one incident. He probably shouldn’t have thrown the chair. It [doesn’t] matter to me.

“But the other things—to have his guys all graduate, make sure they get their education—well, throw some more chairs, man. Some of these coaches [with] these dumb-ass kids that they’re turning out, they’re doing an injustice to what education is supposed to be about. Assure your young people that they will get an education because that’s what you owe them. Above all, that’s why they should be going to school.”

DO NOT OFFER JIM BROWN A WHEELCHAIR

“I just started in the last year thinking about [turning 80],” he discloses, wringing his massive hands, as he frequently does. His mangled fingers look like they’ve been stepped on by linebackers. “Eighty is the first thing that I’ve ever thought about when it comes to age; 60 or 50 didn’t bother me because I was rolling and rumbling and moving around. But I’m looking at 80 and then looking at me,” he says turning his head from side to side. “Eighty is here and I’m over here—and yet this is me. I’m working it out.”

Some people may take the attitude of “Oh, it’s just another year.” Jim Brown is clearly not one of those people. He’s not shy about admitting just how much thought he’s given to his 80th birthday.

“Man, it’s like an amazing place to be because it seems like I jumped from 60 to 80. When I think of 80, I think, ‘Boy that’s an old sucker,’” he snickers. “I mean not in a negative way; it’s just like 80 is a whip. ‘I’m 80?’ When I’m getting up out of chairs and certain things, I know that I’m 80— but then on the other hand when I catch the golf ball the right way, that’s not the way 80-year-old guys hit it.”

PHOTO: CATHRINE WHITE

In a somber voice, he says, “It’s an experience, and I’ll tell you it’s challenging because you can’t do physically, obviously, things that you could do and the ordinary things.”

NFL players in their 20s have trouble getting out of bed and walking down a flight of stairs, especially on a Monday. Throw Father Time into the mix and it’s easy to understand why Brown would use a cane on occasion.

“If I’m coming through an airport and the guy says, ‘Mr. Brown, you want a wheelchair?’ Wheelchair? What you mean, man? I don’t want no wheelchair. It’s like damn,” he says with a deep, easy laugh.

“The reality of [turning 80] makes me so glad that I’m in the place that I am because it makes me really happy to have my families together and we’re sound. All of my preparations are based upon making sure that they have a great life and they can live with dignity and explore when I’m out of here. I think of leaving, and it’s not a negative because the age talks to you. What’s left for you is the good that you can do to help others—and not much else.”

If he weren’t working with people to help them change their lives for the better, then he would be on the golf course every day. He’s happy to have some variety in his life. He stays on the go, traveling between his homes in Los Angeles and Miami and to Cleveland, where he’s a special advisor for the Browns. One day he’s receiving an award from Jesse Jackson, another day it’s Muhammad Ali.

Brown was honored with the Muhammad Ali Humanitarian Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2014 Muhammad Ali Humanitarian Awards, which served as a reunion for the first time in 47 years for five sports heroes—Brown, Ali, Bill Russell, Bobby Mitchell and John Wooten—who attended the legendary Cleveland Summit at the office of Brown’s Negro Industrial Economic Union on June 4, 1967. Brown spearheaded that meeting so an illustrious group of professional African-American athletes could meet with Ali to discuss the fighter’s refusal to be inducted into the U.S. Army when the country was at war with Vietnam. The sports stars decided to support the world heavyweight boxing champion’s controversial stance and held a historical press conference at the office to declare solidarity with Ali.

Amer-I-Can, the vehicle that introduced him to Monique, keeps him busy as well. The two met in the green room at a television station in Buffalo, New York in 1995. Brown was there to talk about his program that educates and rehabilitates gang members; Monique, then 21, was there for a modeling gig. She was hooked after listening to her future husband speak about his foundation, accepted his invitation to accompany him to a press conference later that day and took Amer-I-Can’s life management skills training course so she could teach her community. The rest is history.

Like him, Monique is strong. She’s also quite active in Amer-I-Can, which Brown says gives his wife a sense of self—not to mention helps keep the marriage solid.

“I love Monique, and I admire her strength,” he shares. “She is at least my equal when it comes to her character and her intentions about life. She’s a good person, and she is not going to be controlled or dominated. She will work with me and she’ll work with other people. She has that in her. It’s a characteristic that I truly like. If she didn’t have that, I don’t think we’d be together. But she cares about people.”

His zeal for social and racial justice has never waned. He no longer wears a red, black and green (colors of the Pan-African flag) kufi, but his passion hasn’t dissipated.

“My life being a Black man in this world occupied a lot of my life—and not in a negative way but in a positive way,” he divulges. “When I discovered racism as a little boy, I thought it was terrible to denigrate another human being because of their color. I couldn’t accept it. So much of what I did and so much of how I carried myself and so much of my work is based upon overcoming that particular condition. It’s important that people understand that I have never accepted racism. I’ve always thought about it, worked against it, tried to figure ways to overcome the lack of equal opportunity by creating companies that would hire Black people and always pushing talented Black people and pushing Black people in general to do better.”

As he nears 80, he feels like his time to be effective is running out. “This is my last shot at really doing something about the violence because the violence is escalated now. Little black kids are killing each other all over the country.”

At an anti-violence conference called The Summit II in Newark, New Jersey last September, Brown announced he was “passing the torch” to Ray Lewis, the former NFL linebacker and future Hall of Famer, as a face and advocate for a national campaign to help curb urban violence. For the past two years, Lewis has participated in the annual Jim Brown Legends of Football event that takes place during Super Bowl Week and addresses the state of the game as well as players’ community responsibilities.

Brown can feel pretty good about himself these days for all that he has done— everything from speaking to prison inmates, to paying for funerals, weddings and diapers through his foundation.

“The good thing is that my life is in order, and I’m relevant,” he states proudly. “I’m relevant because I work and I affect things. I was helped when I was a young kid by people, and I’ve helped people. The contribution you make to the lives of others makes you relevant—and that’s a good feeling.”

He gets a kick out being stopped in an airport—not by someone offering him a wheelchair but instead by grateful strangers.

People say, ‘Mr. Brown, thank you so much for what you do for us.’ The genuine attitude that they have is so fulfilling,” he enthuses. “They don’t want an autograph. They just want to say thanks. I don’t go around resisting feeling good about a compliment when they are genuine.”

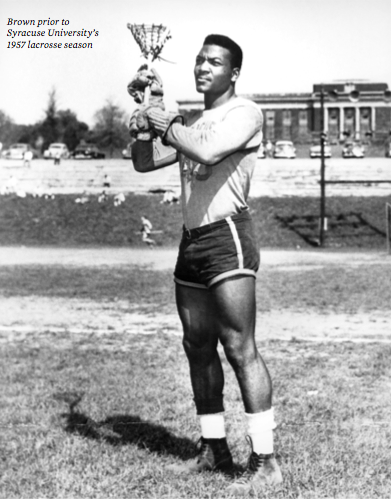

PHOTO: COURTESY SYRACUSE ATHLETICS

JIM BROWN WANTED TO GO OUT ON TOP

No offense to Kobe Bryant but Jim Brown feared becoming what the Lakers star has become this season. That’s why the football icon retired from sports as the reigning MVP instead of being forced out of the game due to declining skills like Bryant and so many other athletes before and after him.

“There’s nothing [they] can say because it’s a year too late. I didn’t want to be in that kind of situation where people would give me the benefit of the doubt or look at me with a sense of pity,” he says with a chuckle. “I always [wanted] to say, ‘I played nine years, never missed a game, and I was the most valuable player in the league in the last year.’ And I’ll leave it at that.”

Jim Brown didn’t just play nine years. He truly ruled for nearly a decade. Cleveland’s number one (sixth player overall) draft pick in 1957 earned Rookie of the Year honors that year, as well as MVP in 1957, 1958 and 1965. The bruising fullback who literally ran over defenders led the league in rushing eight times—a record that no player has come remotely close to breaking— and was a nine-time Pro Bowler. He retired as the NFL record-holder in 15 categories, including highest average yard gain rushing in a career with 5.22—a number no running back after him has reached except Jamaal Charles of the Kansas City Chiefs.

Brown’s lone championship ring came when Cleveland won the 1964 NFL Championship Game, which pre-dates the Super Bowl. A month prior, Brown’s first movie, Rio Conchos, was released. In the summer of 1966, while working on the film The Dirty Dozen with Lee Marvin, Ernest Borgnine and Charles Bronson in England, Brown abruptly retired at the age of 30 rather than leave the movie set to report to training camp. Filming had been delayed a few weeks, making it impossible for him to report to the Browns on time and fulfill his studio commitment.

“People don’t know I became a movie star. I didn’t become [a] movie actor,” he boasts. “A movie star has a power of drawing the finances that’s needed to support the film. I was a bankable star.”

For Brown, the allure of the silver screen, and sharing it with beautiful actresses like Diahann Carroll and Raquel Welch, was just as potent as the thrill of athletic competition. Brown even broke boundaries in his film career. The 1969 flick 100 Rifles, in which Brown co-starred with Welch, was one of the first major studio films to feature an interracial love scene.

But c’mon, Jim. Tell us that at some point you missed the pigskin. Right?

“I’ve never missed a day of football,” says the rare member of three hall of fames—pro football, college football and lacrosse. “I don’t miss a day of anything. Missing means you’re living in the past— you ain’t got nothing going on. No, I never missed it at all, but it did not mean I didn’t appreciate it. I recognize it for what it was. It was a stepping stone. It rescued me at a time when there were no parents there that were well off. It allowed me to form an identity, and I appreciate and respect it for that. But it doesn’t represent 25% of who I am. There are so many things in my life that are more important.”

Brown maintains a home on St. Simons Island off the southern coast of Georgia, where he was born. His father, Swinton, abandoned him when he was a mere two weeks; his mother, Theresa, left when he was 2 years old to work as a maid on Long Island, New York. Raised by his great-grandmother, Brown wouldn’t see his mother again until she sent for him six years later. In Manhasset, on the island’s North Shore, sports became his savior.

“It was just me and my mother. We were renting the downstairs of a two-story house,” he recalls. “It could have been real scary because she had to work and take care of us. I had to make choices. Football played a great part in giving me a certain amount of stability and a certain confidence. It was never my life. My mind was always wandering and analyzing. It ended up that philosophy was my best course in school.”

A sly smile spreads across his face and he glances down, as if he’s revealing a secret. Despite being drawn to philosophy, he realized that he could be a quick success in football due to his size and speed and make good money at the same time.

Three men in Manhasset played influential roles in keeping him on the right path and Brown will never forget them. Ken Molloy, a lawyer and later a New York State Supreme Court judge, steered the talented athlete to his alma mater, Syracuse University, where Brown played football, lacrosse, basketball and ran track (he also qualified for the 1956 Olympics as a decathlete, but passed on the opportunity in order to focus on football). Molloy also raised enough money to pay Brown’s first-year tuition when the school didn’t offer him a scholarship. Brown is also grateful to his high school football coach Ed Walsh, as well as Manhasset school superintendent Dr. Raymond Collins.

“Those were the three people that formed the way I look at things, my belief in people and my representatives of what good people should be like,” says Brown. “I always feel humble to their existence because at the time that they took me under their wing, I was just a child. I have a great appreciation for the things that have been done for me—the encouragement, the motivation.”

Friendships are something he treasures immensely. His “dear friend” is Bill Russell, the former NBA great, and someone “very special” to him is New England Patriots head coach Bill Belichick. “These people make up the best of everything because they have honor,” Brown says. “They have dignity. They have honesty. I’m not saying that they’re angels. [But] I can count on them, and I love that.”

Brown wasn’t an angel either for all of his 80 years, but what’s most important to him is who he is now—and that’s not a puppet or a slave.

10 LITTLE-KNOWN FACTS ABOUT JIM BROWN

- He played football, lacrosse, basketball and ran track at Syracuse University

- He’s the only living person in three sports-related halls of fame: Pro Football Hall of Fame, National Lacrosse Hall of Fame and College Football Hall of Fame

- His favorite course at Syracuse University was philosophy

- He starred in more than 35 films, including 100 Rifles with Raquel Welch, one of the first major studio films to feature an interracial love scene

- He got into Augusta National Golf Club to see Lee Elder compete at the 1975 Masters, the first time an African American golfer had been invited to play in the legendary tournament, by posing as chauffeur for Maggie Hathaway, an actress, golfer and golf writer who fought for integration of the sport. Once inside, Hathaway arranged a caddie credential for him.

- He helped Earth, Wind & Fire gets its first record deal

- He was so close to President Richard M. Nixon that he only had to give an hour notice before visiting the White House

- He’s a minority owner in the Major League Lacrosse team, the New York Lizards

- He and Michael Jackson were such good friends that the King of Pop used to ride with Brown occasionally to Los Angeles International Airport

- He mentored young people in the music business. Rapper Big Daddy Kane used to bring a young Jay-Z to Brown’s Hollywood Hills home.

Photo Credit: Taj Stansberry