Getting pulled over is nerve-wracking. In those moments, knowing your rights isn’t just a talking point—it’s your most powerful tool. The baseline rule is that a police officer cannot search your car without a warrant. But the law is rarely that simple, and several major exceptions can change everything.

Understanding Your Rights During a Traffic Stop

The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is your shield against unreasonable searches and seizures. While we often think of our homes as castles, the law treats our cars a bit differently. You have a lower expectation of privacy on the road, which gives law enforcement more flexibility to conduct warrantless searches under the right conditions.

But that flexibility isn’t a blank check. An officer’s authority has clear limits, and understanding them helps you navigate a traffic stop with confidence. The most important thing to remember is that a simple traffic violation, like speeding or a broken taillight, does not automatically give an officer the green light to toss your car. They need more.

When Can Police Search Without a Warrant?

Several situations allow an officer to legally search your car on the spot. Recognizing these scenarios is the first step in protecting your rights.

- You Give Consent: If an officer asks, “Do you mind if I take a look inside your vehicle?” and you say yes, you’ve just waived your Fourth Amendment protections. It’s that simple.

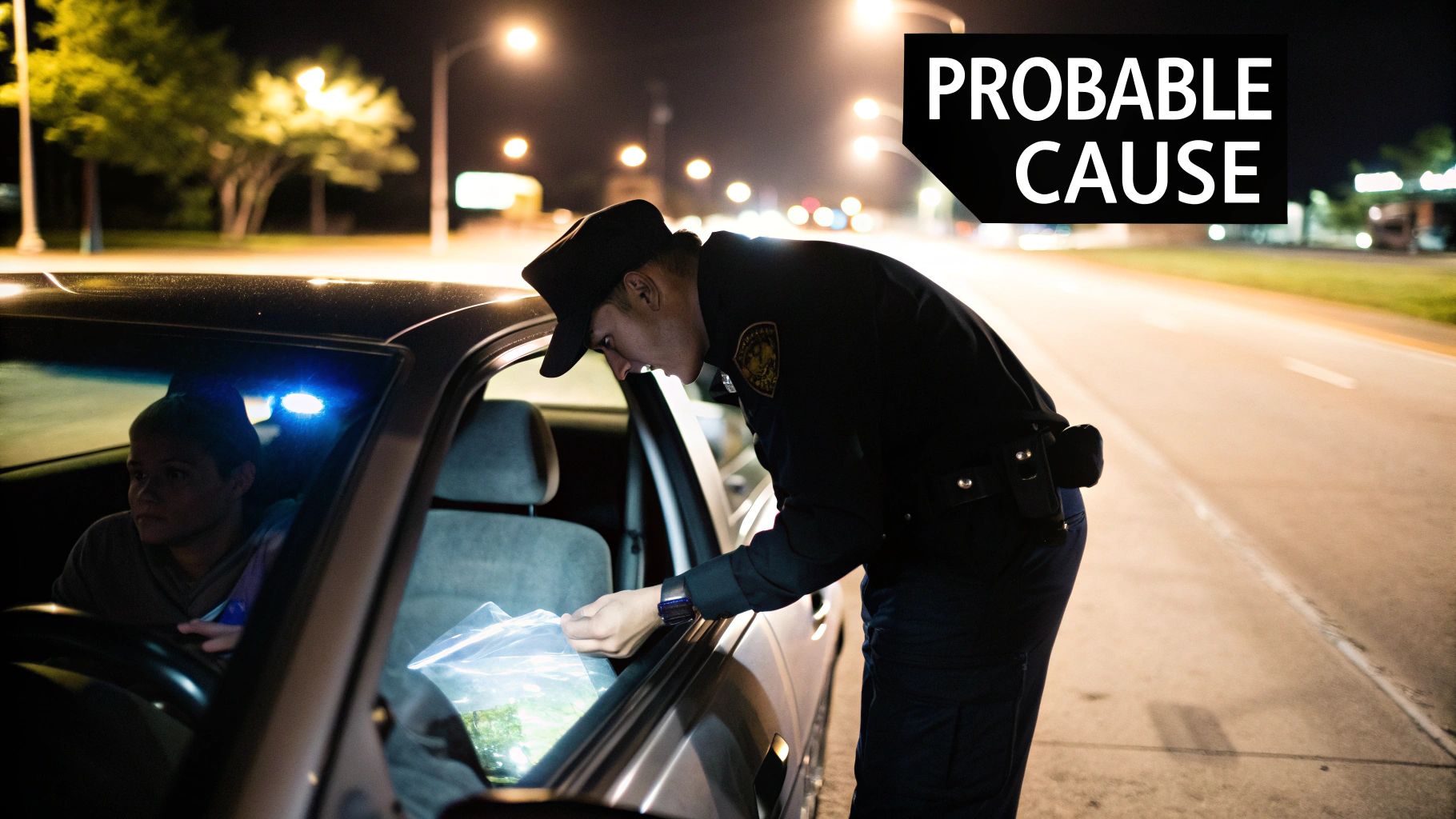

- They Have Probable Cause: This is a big one. If an officer sees, smells, or hears something that gives them a reasonable belief that your car contains evidence of a crime—the distinct smell of marijuana, for example—they can conduct a search.

- Illegal Items are in Plain View: The “plain view” doctrine is straightforward. If an officer can see drugs, a weapon, or other contraband just by looking through your car window, they have the legal right to search the vehicle.

- A Search Incident to a Lawful Arrest: If you are lawfully arrested during the traffic stop, police may have the authority to search your vehicle, though specific rules govern the scope of that search.

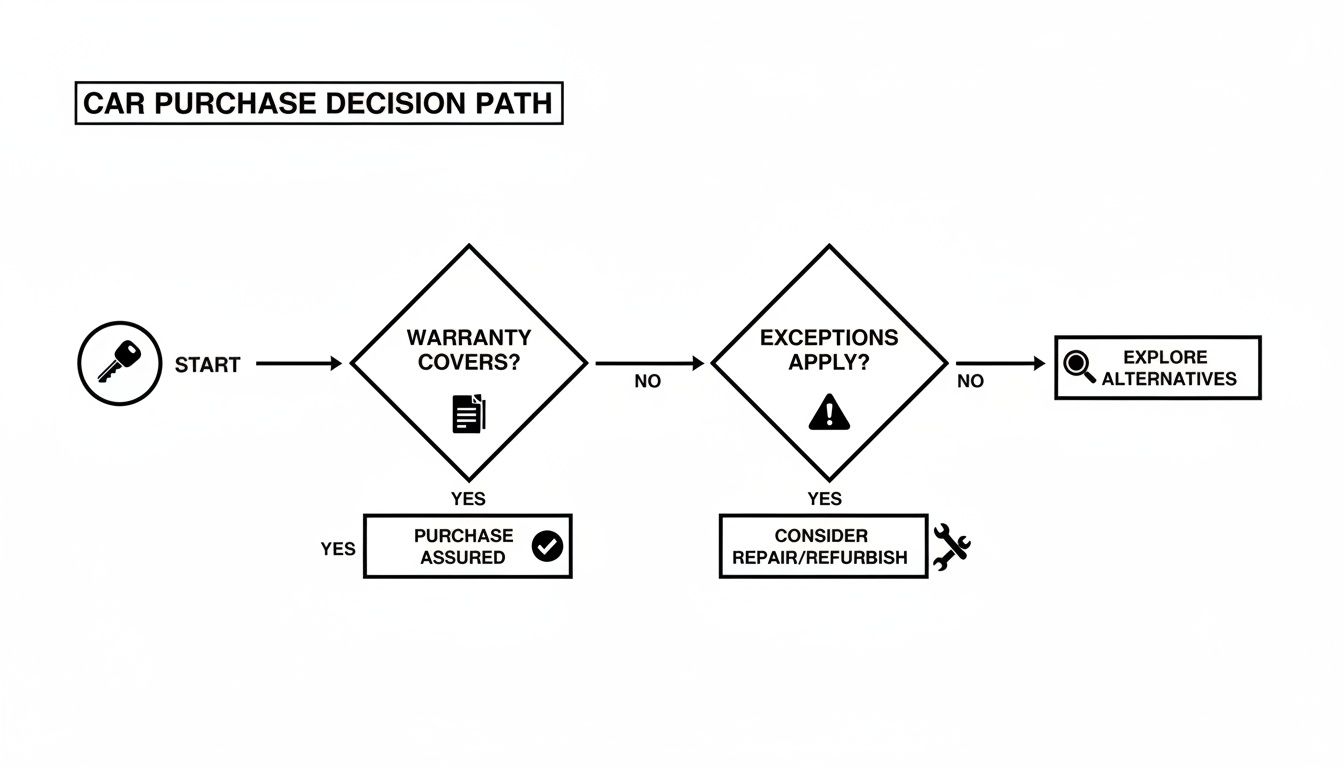

This decision path helps visualize how the law works in practice. A warrant is the default, but these common exceptions create legal detours.

As the infographic shows, while the warrant is the standard, it’s the exceptions that most often determine whether a roadside search is considered lawful.

The Role of Probable Cause and Plain View

While a warrant is the gold standard for a legal search, the reality on the road is entirely different. The most common justification an officer will use to search your car without a warrant is probable cause—a critical legal concept that separates an officer’s hunch from their lawful authority.

Think of probable cause not as a vague suspicion but as a reasonable belief, grounded in specific facts and circumstances, that a crime has occurred or that evidence of it is in the vehicle. It has to be something an officer can point to.

For example, getting pulled over for speeding alone doesn’t give an officer probable cause. But if that officer smells alcohol on your breath and sees empty beer cans on the floor, those tangible facts build a case for probable cause to search for more open containers.

The Plain View Doctrine Explained

One of the most direct routes to probable cause is the Plain View Doctrine. The rule is just what it sounds like: if an officer is legally where they’re allowed to be and spots something illegal just by looking into your car, they can search it.

There are two key conditions here:

- Lawful Vantage Point: The officer must have a legal right to be where they are, like standing beside your car during a legitimate traffic stop.

- Immediately Apparent: The item’s illegal nature has to be obvious. A bag of what looks like marijuana on the dashboard is immediately apparent; a closed, opaque backpack is not.

This doctrine means your car’s windows don’t offer a complete shield of privacy. What an officer can see from the outside can absolutely become the justification for a much deeper search.

What Creates Probable Cause

So, what real-world signs are enough to cross the line from a simple suspicion to legitimate probable cause? It always comes down to the “totality of the circumstances,” but a few classic examples give police a strong legal basis to search.

Examples That Often Justify a Search

- The Smell of Contraband: The distinct odor of marijuana (especially where it remains illegal or driving under its influence is prohibited) is a long-standing trigger for a search.

- Visible Drug Paraphernalia: Seeing items like pipes, bongs, or needles out in the open almost always establishes probable cause.

- Admission of Guilt: If you or a passenger admits to having something illegal in the car, that statement alone can be enough to justify a search.

- Contradictory or Evasive Answers: While nervousness is expected, giving conflicting stories or highly suspicious answers can contribute to the bigger picture of probable cause.

What Does Not Create Probable Cause

On the other hand, an officer can’t search your car based on weak reasoning or personal bias. The law is meant to protect you from searches based on stereotypes or gut feelings.

Situations That Generally Do Not Justify a Search

- Simple Nervousness: Being anxious during a traffic stop is a perfectly normal reaction. It is not a reliable sign of criminal activity.

- Refusing a Search: Politely declining an officer’s request to search your car cannot be used as the reason to search it anyway. You are simply asserting your rights, not admitting guilt.

- Driving in a “High-Crime” Area: Your location, by itself, is never enough to justify a vehicle search without other specific, incriminating facts.

Police pull over more than 50,000 drivers every day, which adds up to over 20 million stops a year, according to the Stanford Open Policing Project. While searches only occur in a small fraction of those stops, the data shows that Black drivers are searched at disproportionately higher rates. You can read the full research on vehicle crime and enforcement trends to learn more.

Navigating Consent Searches and Your Right to Say No

Beyond having probable cause, one of the easiest ways for police to legally search your car is much simpler: they just ask for your permission. When an officer asks, “Do you mind if I take a look inside your vehicle?” they are asking you to voluntarily waive your Fourth Amendment rights. If you say yes, you have given consent, a powerful and common exception to the warrant requirement.

This interaction puts the power squarely in your hands. But let’s be honest, it’s a high-pressure situation. Many people agree to a search because they think it will make things go faster or they feel like they don’t have a choice. The truth is, you absolutely have the right to say no.

Understanding Voluntary Consent

For your consent to be legally sound, it has to be given voluntarily. This is a critical detail. It means you can’t be threatened, coerced, or tricked into giving permission. An officer can’t legally suggest that you’ll face worse trouble for refusing, or say something like, “If you don’t consent, I’ll just go get a warrant anyway.”

Your agreement has to come from your own free will. If a court later determines that you were intimidated into agreeing, the search could be ruled illegal, and any evidence they found would be thrown out.

This is a key point because officers are trained to ask for consent in ways that can feel authoritative. They might use a casual tone to put you at ease or ask leading questions like, “You don’t have anything to hide, do you?” These are tactics. They are designed to make saying “no” feel like an admission of guilt, but it’s not—it’s just you asserting your rights.

You Have the Right to Refuse a Search

If you remember one thing from this guide, let it be this: you can, and often should, refuse to consent to a search. A polite but firm refusal is your constitutional right. It cannot be used against you as a reason to suspect you of a crime.

So, how do you do it? You don’t need a big legal speech. Simple and clear is always best.

- “Officer, I do not consent to any searches.”

- “I am not giving you my permission to search my vehicle.”

You do not need to explain why you are refusing. Simply stating your position is enough. The most effective strategy is to remain calm, be polite, and stand your ground.

Once you have clearly stated your refusal, the officer cannot legally search your car based on consent alone. At that point, they need another legal reason to proceed, like developing probable cause on their own.

Deciding whether to consent or refuse a search can feel like a gamble, but understanding the potential outcomes can help you make an informed choice. Here’s a quick breakdown of what each path might look like.

Consent vs. Refusal Potential Outcomes

| Action | What It Means | Potential Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Giving Consent | You voluntarily waive your Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable searches for this specific interaction. | The officer can legally search your car. If anything illegal is found, it can be used against you in court. |

| Refusing Consent | You are asserting your constitutional right. This action alone is not evidence of guilt. | The officer cannot search your vehicle without another legal justification. They may still try to develop probable cause, but you have preserved your rights. |

Ultimately, refusing consent protects your constitutional rights and limits the officer’s legal authority on the spot, while giving consent opens the door to a full search and potential legal trouble.

Defining the Scope of Your Consent

What if you do decide to agree to a search? It’s important to know that consent doesn’t have to be a free-for-all. You have the right to limit how and where the officer can look.

For example, you could say, “You can look in the trunk, but I do not consent to a search of the passenger cabin.” If an officer goes beyond the limits you set, any evidence they find in those off-limits areas could be suppressed in court.

Be warned, however: this can get legally complicated very quickly. If you give a general, undefined “okay” to a search, a court might later interpret that as permission to look inside any unlocked bags or containers in your car. The cleanest and safest approach is almost always to refuse any search from the outset.

While specific data on consent rates isn’t tracked nationally, we do know that searches are a frequent part of the 20 million traffic stops that happen each year in the U.S. Troubling analyses also show that Black and Hispanic drivers are searched at significantly higher rates than white drivers. You can discover more insights about these contact patterns on the BJS website. This disparity makes it even more critical for every driver, regardless of background, to know and be prepared to exercise their rights.

When an Arrest or Impound Leads to a Search

Most traffic stops are routine, ending with a warning or a ticket. But sometimes, they escalate. An officer might discover an outstanding warrant, find evidence of a DUI, or witness another crime, leading to an arrest or the impounding of your car.

When this happens, the rules of the game change completely. These events can trigger a warrantless search of your vehicle, but it’s not a free-for-all. The law sets very specific, narrow boundaries to balance police safety and evidence collection with your fundamental right to privacy.

A simple traffic violation can spiral into a serious criminal matter in seconds. An arrest immediately shifts the legal landscape, altering what an officer is permitted to do with your car. Knowing your rights in these high-stakes moments is critical, especially when the situation gets complicated. For a deeper look into a common scenario, a DUI first offense guide can help you understand the legal road ahead.

Understanding a Search Incident to Arrest

For decades, the police had broad power here. If you were arrested near your car, they could pretty much search the entire passenger area. But that all changed with a pivotal 2009 Supreme Court decision that reined in that authority.

The old standard, set by a 1981 case called New York v. Belton, is no longer the law of the land. Today, the much stricter rules come from Arizona v. Gant. This landmark case established that police can only search a vehicle as part of a lawful arrest in two very specific situations. You can learn more about the findings that shaped modern vehicle search laws to see just how much this ruling impacts traffic stops today.

The two justifications are now crystal clear:

- The Lunge Area: An officer can search the area within your immediate control—what lawyers call the “lunge distance”—but only if you are unsecured and could realistically grab a weapon or destroy evidence.

- Evidence of the Arresting Offense: Police are allowed to search the vehicle if it’s reasonable to think it holds evidence of the specific crime you’re being arrested for. If you’re arrested for drug trafficking, for example, it’s reasonable to believe drugs might be in the car.

This distinction is huge. If you’re arrested for driving on a suspended license, handcuffed, and secured in the back of a squad car, an officer generally cannot then go back and search your vehicle. You’re no longer a threat, and your car isn’t likely to contain evidence of a suspended license.

What Happens During an Inventory Search

There’s another common way police can legally search your car without a warrant: when your vehicle is impounded. This can happen after an arrest, if your car is disabled after an accident, or even if it’s just parked illegally and gets towed.

Once your vehicle is in police custody, officers will perform what’s called an inventory search. The official reason for this isn’t to dig for criminal evidence, but rather to handle administrative tasks.

Primary Goals of an Inventory Search

- Protect Your Property: Police create a detailed log of everything in your vehicle. This protects the department from any future claims that your belongings were stolen or lost while in their care.

- Ensure Officer Safety: The search makes sure there are no dangerous items, like hidden weapons or hazardous materials, inside the vehicle before it’s moved to a storage lot.

- Document Valuables: It creates a formal record of any valuables left behind, which is important for both you and the police.

Even though an inventory search isn’t supposed to be an investigation, it has a critical catch. If police happen to find illegal items—like drugs or an unregistered firearm—during a lawful inventory search, that evidence can absolutely be used against you. The key is that the search must follow a standardized, routine department policy. It can’t just be a pretext for officers to rummage through your car hoping to find something incriminating.

More Exceptions to the Warrant Rule

Probable cause, consent, and searches connected to an arrest are the heavy hitters—the most common reasons an officer might search your car. But they aren’t the end of the story. The courts have carved out a few other key exceptions, each built for specific, fast-moving situations you might encounter on the road.

These rules all stem from one core idea: a car is not a castle. Because it’s mobile and driven in public, the law says you have a lower expectation of privacy in your vehicle than you do in your home. This gives officers more legal flexibility during a traffic stop than they’d have standing on your front porch.

The Automobile Exception

This is one of the oldest and most powerful exceptions on the books. The Automobile Exception dates all the way back to the Prohibition era, born from a very practical problem: cars can drive away with evidence while police are trying to get a warrant.

Because of this simple reality, the Supreme Court has consistently held that an officer doesn’t need a warrant to search a vehicle if they have probable cause to believe it contains evidence of a crime. It’s not a free-for-all; they still need a solid, fact-based reason for the search. They just don’t have to get a judge’s sign-off first.

The Automobile Exception essentially fuses the probable cause requirement with the inherent mobility of a vehicle, allowing for immediate, warrantless searches when evidence of a crime is suspected to be inside.

Imagine an officer pulls you over for speeding. A few minutes earlier, a credible informant told them your specific make and model of car was being used to transport stolen laptops. With that tip establishing probable cause, the officer could likely search your trunk on the spot.

Exigent Circumstances

Another critical exception hinges on exigent circumstances. This is just a legal term for an emergency—a situation where police must act right now to prevent something much worse from happening.

When it comes to vehicle searches, this exception usually kicks in when an officer reasonably believes:

- Evidence is about to disappear. If an officer approaches a car and sees a passenger frantically trying to swallow a bag of pills, they may be justified in entering the vehicle immediately to stop that evidence from being destroyed.

- There’s an immediate threat to public safety. Police chasing a suspect believed to have a bomb in their trunk aren’t expected to pause and get a warrant before searching the car. The immediate danger outweighs the warrant requirement.

This exception is a narrow one. It’s not a shortcut for officers who feel rushed. They must be able to point to specific facts showing why an immediate, warrantless search was absolutely necessary to prevent a greater harm.

The Terry Frisk for Weapons

Finally, there’s a limited type of search known as a Terry Frisk, named after the landmark Supreme Court case Terry v. Ohio. This isn’t a search for evidence of a crime—it’s purely about officer safety.

For an officer to perform a “frisk” of your car’s passenger area, two things must be true:

- You were lawfully stopped.

- The officer has a reasonable suspicion (a step below probable cause) that you are armed and dangerous.

This can’t be a mere hunch. The officer needs concrete facts. For instance, if you’re pulled over late at night in a high-crime area and the officer sees you shove an object shaped like a handgun under your seat, that might be enough to justify a protective search.

It’s crucial to know this search has strict limits. The officer can only check places where a weapon could reasonably be stashed, like the glove compartment or under the seats. They can’t start opening small containers or reading your mail under the banner of a weapons search. It’s strictly a hunt for weapons, not a fishing expedition for anything else.

A Practical Guide for Handling a Traffic Stop

It’s one thing to understand your rights in theory, but it’s an entirely different challenge to assert them during a high-stress traffic stop. When you see those flashing lights, the primary goal is to keep the encounter calm, safe, and as brief as possible. This guide offers a clear, step-by-step approach to managing the situation correctly from the moment you’re pulled over.

The first few seconds of a traffic stop set the tone for the entire interaction. Your actions can immediately show the officer that you are cooperative and not a threat, which goes a long way toward de-escalating the situation from the start.

Initial Steps During the Stop

The moment you see the police lights, find a safe spot to pull over. Acknowledge the officer by using your turn signal, then pull to the right shoulder of the road as quickly as is safely possible.

Once you’ve stopped, take these immediate actions to create a smooth, predictable interaction:

- Turn off your engine. This is a clear signal that you have no intention of fleeing.

- Turn on your interior dome light if it’s dark outside. This simple act dramatically improves visibility for the officer.

- Keep your hands visible. The best practice is to place both hands on top of the steering wheel and leave them there.

- Prepare your documents. You’ll need your driver’s license, registration, and proof of insurance, but don’t start rummaging for them. Wait for the officer to request them before reaching into your glove box or wallet.

These initial steps are about demonstrating respect for officer safety, which helps ensure the stop remains routine. But remember, cooperation doesn’t mean surrendering your rights. If a minor traffic issue escalates, knowing the rules becomes critical. For simple tickets, it’s worth exploring a traffic ticket deferral guide to understand your options for handling the citation later.

How to Assert Your Rights Calmly

The pivotal moment often comes when an officer asks for consent to search your car. This is where knowing when can a police officer search your car truly matters, and your response is crucial. You must be clear, polite, but firm.

“Officer, I do not consent to any searches.”

That phrase is powerful and sufficient. You are not required to give a reason, make an excuse, or justify your decision. Asserting your Fourth Amendment right is not an admission of guilt, and your refusal cannot be used as the sole justification for a search.

Roadside Stop Dos and Don’ts

Navigating a traffic stop is about balancing cooperation with the protection of your constitutional rights. This table provides a quick reference for best practices during any roadside interaction.

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Pull over quickly and safely. | Keep driving or look for an “ideal” spot. |

| Keep your hands on the steering wheel. | Make sudden movements or reach for items. |

| Be polite and respectful. | Argue, raise your voice, or be confrontational. |

| Provide your license, registration, and insurance. | Volunteer extra information or admit guilt. |

| Clearly state, “I do not consent to a search.” | Give excuses or reasons for refusing a search. |

By staying calm and following these guidelines, you can navigate the stop safely while protecting your constitutional rights.

Common Questions About Vehicle Searches

Even when you know the basic rules, the pressure of a traffic stop can create confusion. Let’s clear up some of the most common legal gray areas people encounter when an officer wants to search their car.

Can Police Get a Warrant on the Spot if I Refuse a Search?

It’s almost unheard of for an officer to get a search warrant during a traffic stop. The process is anything but instant—it requires the officer to draft a formal affidavit, detail their probable cause, and track down a judge for approval.

Crucially, your refusal to consent cannot be used as the reason to get that warrant. If you say no and the officer doesn’t already have probable cause, their options are usually limited to writing you a ticket or letting you leave.

Does the Smell of Marijuana Justify a Car Search?

This is a tricky one, and the answer completely depends on your state’s laws. In places where marijuana remains illegal, its distinct odor is almost always considered enough to establish probable cause for a search.

However, the legal ground is shifting in states that have legalized marijuana for recreational or medical use. Courts are increasingly deciding that the smell alone isn’t enough, since having it might be perfectly legal. An officer might need something more—like the smell of burnt marijuana suggesting illegal impairment while driving—to justify a search. You have to know your local laws.

Can Police Search My Phone if They Find It?

Absolutely not, at least not without a warrant. The Supreme Court has been very clear on this. Our phones hold an incredible amount of private information, giving them a much higher level of Fourth Amendment protection than, say, a glove compartment.

Even if police have a valid reason to search the physical space of your car, that authority does not magically extend to the digital contents of your phone. They need a separate warrant specifically authorizing a search of your phone’s data.

What if Police Illegally Search My Car and Find Evidence?

This is where your constitutional rights really kick in. If evidence is discovered during an illegal search, your attorney can file what’s called a “motion to suppress.” This motion argues that the search violated your rights.

If the judge agrees, the evidence is thrown out and cannot be used against you in court. This is the “exclusionary rule,” a powerful check designed to discourage police from conducting unlawful searches in the first place. If you suspect your rights were violated, your first call should be to an expert in criminal defense. It’s the most critical step you can take to protect yourself.

Navigating the complexities of a vehicle search can be overwhelming, but you don’t have to do it alone. The Haute Lawyer Network connects you with premier, vetted attorneys who can protect your rights and provide expert legal guidance. Find the right legal professional for your needs today.