When you buy property with someone else, how you take title is one of the most critical decisions you’ll make. It’s a choice that defines not just ownership percentages, but also what happens to the property when one owner passes away, gets into financial trouble, or wants to sell.

The core distinction between tenants in common vs joint tenancy comes down to one thing: inheritance. With a joint tenancy, your interest automatically transfers to the surviving co-owner upon death, completely bypassing your will. A tenancy in common, however, allows your distinct share to be passed to whomever you name in your estate plan.

Understanding Your Co-Ownership Options

This isn’t a modern legal quirk; the roots of these ownership structures go deep, tracing back to English common law in the 13th century. Feudal lords needed a way to keep their landholdings consolidated. Joint tenancy was formalized to prevent property from being fragmented by inheritance, built on the “four unities” of time, title, interest, and possession.

For those navigating the complexities of property ownership, a deep dive into sophisticated real estate law can provide critical context. Choosing the right structure will have lasting consequences for your assets and your legacy.

Comparing The Two Structures At A Glance

Making an informed choice requires a clear understanding of what each structure offers. The table below cuts straight to the key differences.

| Feature | Tenants in Common (TIC) | Joint Tenancy (JTWROS) |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership Shares | Can be unequal (e.g., 70/30) | Must be equal for all owners |

| Right of Survivorship | No; share passes to heirs via will | Yes; share passes to co-owners |

| Control & Transfer | Can sell or will share independently | All owners must agree to sell |

| Probate | Share is subject to probate | Avoids the probate process entirely |

This isn’t a one-size-fits-all decision. The right choice demands a careful look at your relationship with your co-owners, your respective financial contributions, and your ultimate estate planning goals.

Comparing The Two Core Ownership Structures

Choosing between tenants in common and joint tenancy isn’t about which is “better”—it’s a strategic decision based on the specific financial and legacy goals of the co-owners. While both grant co-ownership, they operate on entirely different principles that have profound implications for inheritance, flexibility, and control.

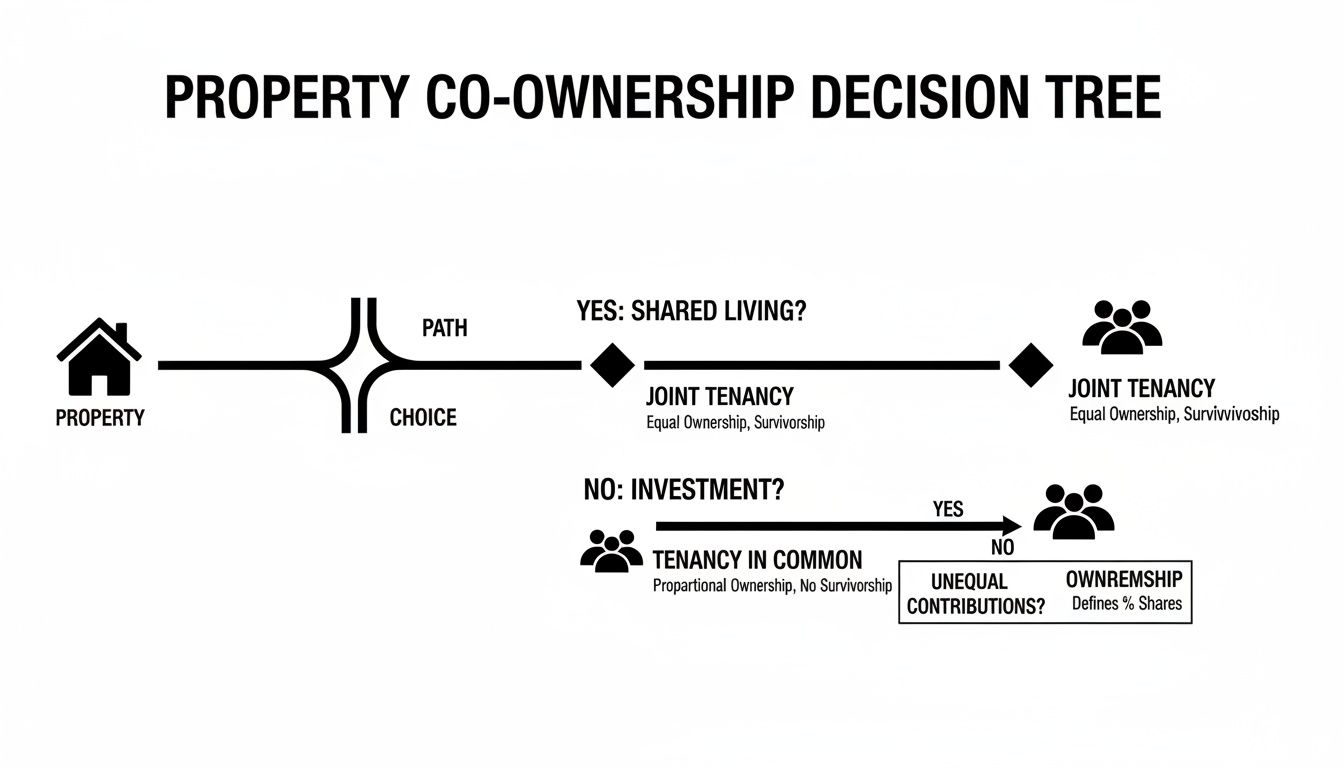

This decision tree cuts through the complexity, showing how your primary objectives should guide your choice.

As the graphic shows, the path diverges immediately based on one critical question: what happens to an owner’s share when they die? This is the core distinction that drives everything else.

To make an informed decision, let’s break down the essential differences side-by-side. The following table provides a clear, at-a-glance comparison of these two fundamental ownership structures.

Key Differences Tenants in Common vs Joint Tenancy

| Feature | Tenants in Common (TIC) | Joint Tenancy with Right of Survivorship (JTWROS) |

|---|---|---|

| Right of Survivorship | No. Your share passes to your heirs via will or probate. | Yes. Your share automatically passes to surviving co-owners. |

| Ownership Shares | Can be unequal (e.g., 70/30). | Must be equal (e.g., 50/50). |

| Creation | Requires only the unity of possession. | Requires the “four unities”: time, title, interest, possession. |

| Transfer of Interest | You can sell or will your share freely. | Selling a share severs the joint tenancy, converting it to a TIC. |

| Probate | Your share goes through probate. | The property bypasses probate. |

| Ideal Use Case | Business partners, unmarried couples, or investment groups. | Married couples or family members seeking seamless inheritance. |

This table lays out the fundamental mechanics, but the real-world implications of these differences are where sophisticated planning becomes essential. Understanding these nuances is critical for asset protection and estate planning.

Dissecting The Right of Survivorship

The defining feature in the tenants in common vs joint tenancy debate is the right of survivorship. This single element dictates the property’s entire succession plan, completely bypassing traditional estate channels like wills and probate courts.

In a Joint Tenancy with Right of Survivorship (JTWROS), this right is automatic and absolute. When one owner dies, their interest in the property is simply extinguished, and the surviving joint tenant (or tenants) instantly absorbs that share. A will or trust has no power to redirect this transfer.

On the other hand, a Tenancy in Common (TIC) completely lacks a right of survivorship. Each owner holds a distinct, separate interest in the property. When a TIC owner dies, their share becomes part of their estate, to be distributed according to their will or, if they die intestate, state succession laws.

Key Insight: Joint tenancy prioritizes a seamless transfer to co-owners, making it a common choice for married couples. Tenancy in common prioritizes testamentary freedom, ensuring an owner’s share passes to their chosen heirs—a vital feature for business partners, blended families, or complex estate plans.

Ownership Shares And Contribution Flexibility

Another critical difference is how ownership stakes are structured. This isn’t just a detail; it directly impacts financial equity and must reflect the reality of each co-owner’s contribution.

Joint tenancy is famously rigid, demanding what legal scholars call the “four unities” of title:

- Time: All owners must acquire their interest at the same time.

- Title: All owners must be named on the same deed.

- Interest: All owners must hold equal shares (e.g., 50/50 for two owners).

- Possession: All owners have an equal right to possess the entire property.

Tenancy in common scraps this rigidity, offering complete flexibility. Ownership shares can be divided any way the parties agree. If one partner contributes 70% of the capital and the other puts in 30%, the deed can reflect that 70/30 split. This is a massive advantage for unmarried partners or investment groups where financial contributions are rarely identical.

Control and Transferability of Interest

The final point of contrast is the level of independent control an owner has over their share. This determines an owner’s ability to sell, mortgage, or gift their portion of the property without needing consent from the other owners.

With a tenancy in common, each owner can sell, gift, or mortgage their individual share without permission. This autonomy provides a much clearer exit strategy for investors and allows for independent financial planning.

A joint tenancy is far more restrictive. Since the ownership is a unified whole, one joint tenant cannot sell their share without severing the joint tenancy. That unilateral action breaks the right of survivorship and converts the ownership structure to a tenancy in common, fundamentally changing the arrangement for everyone involved. The structure is built for unity, not individual maneuverability.

The Financial and Legal Aftermath

Choosing between tenants in common and joint tenancy isn’t just about what’s on the deed. It sets off a chain reaction of financial and legal outcomes that can seriously impact estate plans, asset protection, and tax bills. For high-net-worth individuals, grasping these consequences is crucial for wealth preservation and ensuring your assets go where you intend. The selection you make fundamentally changes how courts, creditors, and the IRS will treat the property.

One of the biggest draws of joint tenancy is its ability to sidestep the notoriously slow and expensive probate process. Thanks to the automatic right of survivorship, the property just flows to the surviving co-owner when one dies, completely outside of a will or the probate court’s control. This can save an incredible amount of time and money, making it a go-to for straightforward estates, especially for married couples.

Probate Avoidance and Its Blindsides

With a tenancy in common, however, the deceased owner’s share is treated as part of their estate. This means it gets pulled into probate, where it’s subject to court supervision, potential will contests, and all the associated fees. The whole ordeal can drag on for months, sometimes years, delaying the final settlement and creating a headache for the heirs.

Crucial Takeaway: While joint tenancy is a sleek tool for avoiding probate in simple scenarios, it can inadvertently blow up a more sophisticated estate plan. Because it overrides a will, it can be a disaster if an owner wanted to leave their share to, say, children from a prior marriage or a carefully structured trust.

Navigating Creditor Exposure

Another battleground where these ownership types clash is creditor risk. The “legal unity” of a joint tenancy can quickly become a massive liability. If one joint tenant racks up debt or gets hit with a lawsuit, a creditor could slap a lien on—and possibly force the sale of—the entire property to get paid. This puts the innocent co-owner’s interest in serious jeopardy.

Tenancy in common offers a much stronger defense here. Since each owner holds a distinct, divisible share, a creditor can typically only go after that specific owner’s interest. This legal firewall shields the other co-owners’ shares from being seized to pay someone else’s debt, providing a critical layer of asset protection for business partners or unrelated co-investors.

Critical Tax Considerations

The tax implications are nuanced but can have a massive financial impact, particularly around gift and capital gains taxes.

If you create a joint tenancy with a non-spouse and put in more than your share of the cash, you might have just made a taxable gift without realizing it. For instance, if you fund 100% of a property’s purchase but title it as joint tenants with an unmarried partner, the IRS could see that as a gift of 50% of the property’s value. That could easily trigger a gift tax filing requirement.

The “step-up in basis” rules at death also work very differently, and this is where the real money is.

- Joint Tenancy (with a non-spouse): When one owner dies, only their portion of the property (usually 50%) gets a “step-up” in basis to its current market value. If the survivor sells later, they’ll owe capital gains tax on all the appreciation tied to their original half.

- Tenancy in Common: The deceased’s specific share gets a full step-up in basis. This means their heirs inherit that portion valued at the date of death, which can dramatically slash or even eliminate their capital gains tax bill if they turn around and sell.

For a high-value, appreciating asset, this distinction could mean a tax difference of hundreds of thousands of dollars. It often makes tenancy in common a far more tax-savvy way to pass wealth to the next generation.

Real-World Scenarios For Each Structure

Knowing the legal theory is one thing, but translating it into practical strategy is where the real value lies. The right choice between tenants in common vs joint tenancy isn’t academic—it hinges entirely on the context of the purchase, the co-owners’ relationship, and their long-term financial and legacy goals. Each structure is a specific tool for a specific job.

To make this clear, let’s walk through common situations where one structure is the obvious winner, providing a clear roadmap for high-net-worth individuals and their advisors.

When Joint Tenancy Is The Clear Winner

The classic, textbook use case for Joint Tenancy with Right of Survivorship (JTWROS) is a married couple buying their primary home. The objective is almost always simplicity and a seamless asset transfer to the surviving spouse.

Imagine a married couple, Sarah and Tom, buying their family home. Their priority is ensuring that if one of them passes away, the other automatically becomes the sole owner without the headache and expense of probate court. Joint tenancy delivers this perfectly. Should Sarah pass, Tom instantly becomes the full owner of the property. It’s efficient, private, and painless.

This structure aligns perfectly with their shared life, making it the default choice for millions of couples.

Key Application: Joint tenancy is ideal for married couples or long-term partners with integrated finances and a shared desire for the property to pass directly to the survivor, bypassing the will and probate.

This isn’t just anecdotal. The data shows that joint tenancy is the overwhelming choice for married couples, accounting for roughly 85% of co-owned primary residences in the U.S. This is in sharp contrast to non-marital co-ownership, where tenancy in common is used in 70% of investment group holdings. Understanding these patterns, often detailed in expert analysis available from resources like LegalZoom, provides valuable insight into property ownership strategy.

When Tenants In Common Provides Essential Flexibility

While joint tenancy excels in its simplicity for married couples, Tenancy in Common (TIC) is the superior choice for nearly every other co-ownership scenario. Why? It offers flexibility and precision that joint tenancy simply can’t match, allowing owners to define their exact interests and control their legacy.

Here are a few scenarios where TIC is indispensable:

- Unmarried Partners with Unequal Contributions: Consider Alex and Ben, an unmarried couple buying a condo. Alex puts down 60% of the down payment and closing costs, while Ben covers the other 40%. A TIC structure allows their deed to reflect this 60/40 split, ensuring their ownership stake precisely mirrors their financial input.

- Business Partners Investing in Commercial Real Estate: Two entrepreneurs purchase an office building as an investment. They absolutely need the ability to sell their individual shares as part of an exit strategy or to pass their interest to their heirs. A TIC structure grants them this autonomy, preventing a business asset from being locked up by a surviving partner.

- Blended Families and Estate Planning: This is a critically important use case. A couple in their second marriage, each with children from a previous relationship, buys a home together. They want to ensure their respective shares of the property go to their own children, not just their new spouse. By holding title as tenants in common, each partner can specify in their will that their 50% interest passes directly to their biological children, protecting that inheritance and preventing future family disputes. With blended families now representing 16% of U.S. households, this has become a vital planning tool.

How To Create And Sever Co-Ownership

The entire legal framework of co-ownership—whether tenants in common or joint tenancy—is locked in the moment a property deed is drafted. The specific language chosen, or even omitted, dictates everything from inheritance rights to who controls the asset. Getting this right from day one is essential to ensuring the title accurately reflects what the co-owners truly intend.

This is where precision is everything. Any ambiguity in the creation process can trigger unintended and costly legal battles down the road.

Establishing The Ownership Structure

To create a joint tenancy, the deed’s language must be explicit and unambiguous. Because its right of survivorship is such a powerful legal mechanism, courts demand absolute clarity that the co-owners intended this specific arrangement. This means satisfying the “four unities” and using precise legal phrasing.

A deed must typically include wording like:

- “As joint tenants with right of survivorship”

- “As joint tenants, and not as tenants in common”

Without this direct declaration, the law in most states will default to the less restrictive form of ownership.

In sharp contrast, a tenancy in common is often the default outcome. If a deed simply conveys property to two or more people without specifying the ownership type, the law presumes a tenancy in common. This structure only requires the unity of possession, making it the standard to ensure owners maintain distinct control over their individual shares.

The Process Of Severance

A tenancy in common is stable; it remains in place unless the owners collectively decide to change it. A joint tenancy, however, is far more fragile. It can be terminated—or “severed”—which instantly converts the ownership into a tenancy in common and, critically, destroys the right of survivorship. Severance can happen voluntarily, but it can also be forced.

Key Takeaway: Severance is a definitive legal action that permanently rewrites the co-ownership agreement. A single joint tenant selling their share to an outsider can unilaterally break the joint tenancy for everyone, converting all interests into a tenancy in common.

A joint tenancy can be severed in several ways:

- Mutual Agreement: This is the cleanest approach. All joint tenants sign a written agreement to sever the joint tenancy, becoming tenants in common.

- Unilateral Action: One joint tenant can act alone to sever the arrangement, without needing consent from the others. This is often done by transferring their interest to a third party or even to themselves via a new deed, an action that shatters the unities of time and title.

- Involuntary Severance: Actions beyond the owners’ control can also sever the tenancy. For example, if a creditor places a lien on one owner’s interest and forces a sale, the joint tenancy is broken.

The ability to unilaterally sever a joint tenancy highlights a crucial point in the tenants in common vs joint debate. The former offers predictable stability for estate planning, while the latter can be upended by the actions of just one co-owner. This is why properly structuring ownership from the start is paramount, which often involves considering more sophisticated tools like trusts. For a deeper look into asset protection, you might find our guide on how to create a family trust insightful.

Strategic Counsel For High-Net-Worth Clients

For high-net-worth (HNW) clients, choosing between tenants in common and joint tenancy is far more than a simple checkbox on a property deed. It’s a critical decision that sits at the very foundation of their wealth preservation and legacy strategy. An attorney’s advice can’t stop at the closing table; it has to consider the client’s entire financial world, from sophisticated estate plans to delicate family dynamics.

A holistic perspective is absolutely essential. The way a property is titled must support the client’s long-term goals, not sabotage them. For instance, defaulting to joint tenancy just to avoid probate can have disastrous unintended consequences, like disinheriting children from a previous marriage or directly contradicting the specific instructions of a carefully drafted trust.

Crafting Bespoke Co-Ownership Agreements

When tenancy in common is the smarter strategic move—which it often is for business partners or individuals with unequal financial stakes—a detailed co-ownership agreement is non-negotiable. This document goes far beyond the deed, creating a clear and enforceable rulebook for how the asset will be managed.

A well-drafted TIC agreement must spell out the specifics:

- Financial Responsibilities: A precise breakdown of how taxes, insurance, maintenance, and other costs will be shared.

- Usage Rights: Clear rules governing who can use the property, when, and under what conditions, including leasing and occupancy.

- Capital Calls: A defined process for funding major repairs or unexpected capital improvements.

- Exit Strategies: An agreed-upon plan for buyouts, rights of first refusal, or how to handle a forced sale if one owner wants out.

This agreement is a powerful risk-management tool. It prevents expensive, relationship-damaging disputes by setting clear expectations right from the start. Without it, co-owners are left trying to resolve disagreements that can quickly spiral into litigation.

Expert Insight: For HNW clients, the standard legal protections are rarely enough. A bespoke co-ownership agreement elevates a simple TIC into a sophisticated business arrangement that protects both the investment and the relationship between the owners.

Integrating Trusts for Enhanced Asset Protection

A truly powerful strategy for HNW individuals is to combine property titling with trusts. Holding a property interest as a tenant in common through a revocable or irrevocable trust provides an unparalleled level of control and protection. This structure allows the property to bypass probate court entirely while preserving the flexibility to direct the asset to specific heirs according to the trust’s terms.

This layered approach also offers a formidable shield against creditors. When an asset is titled within a properly structured trust, it can be insulated from personal liabilities that might otherwise put the property at risk. To provide this level of sophisticated advice, it’s critical to understand the advanced techniques of ultra-high-net-worth estate planning.

Finally, wealth and life are dynamic, and so ownership structures must be as well. Attorneys must insist on periodic reviews of all property titles. Major life events—a marriage, a divorce, a new business venture, or even changes in tax law—can make a once-perfect ownership structure dangerously obsolete. Proactive reviews ensure a client’s titling strategy remains perfectly aligned with their evolving financial and personal goals, securing their legacy for generations to come.

Common Questions in Property Co-Ownership

Even the most thorough guides can leave lingering questions. When advising clients on structuring property ownership, certain practical issues come up time and time again. Let’s address a few of the most frequent queries.

Can You Convert a Joint Tenancy to a Tenancy in Common?

Absolutely. It’s a common and legally straightforward process known as severance. The key outcome of severance is that it permanently destroys the right of survivorship, which is the defining feature of joint tenancy.

This can be done in a couple of ways. All co-owners can mutually agree to the change, signing a new deed to reflect their updated ownership structure. More critically, a single joint tenant can act alone to sever the tenancy by transferring their interest—even if it’s just to themselves—through a new deed. This unilateral action is enough to break the legal “unities” required for joint tenancy, converting the ownership to a tenancy in common for everyone involved.

What if a Tenant in Common Dies Without a Will?

This is where the rubber really meets the road in distinguishing between these two ownership forms. When a tenant in common passes away intestate (without a will), their ownership stake does not simply transfer to the surviving owners.

Instead, their defined share is treated like any other asset and becomes part of their estate. That interest must then pass through probate court, where a judge will distribute it to the deceased’s legal heirs based on state law. While this ensures family members inherit the asset, it also means the original co-owners could suddenly find themselves partners with a distant relative, creating potential management and financial complications.

The Critical Takeaway: Unlike a joint tenancy where the property transfer is automatic and outside the will’s control, a tenant in common’s share is entirely governed by their estate plan—or the lack of one.

Can a Corporation Hold Property as a Joint Tenant?

The short answer is no. The entire concept of joint tenancy hinges on the right of survivorship, which is triggered by the natural death of a co-owner. A corporation, as a legal entity, has a potentially perpetual existence and cannot “die” in the way a person does.

Because of this fundamental difference, a corporation can’t satisfy the conditions for a joint tenancy. When a business entity co-owns property, the structure is almost always a tenancy in common. This allows the corporation’s share to be managed, sold, or transferred as a business asset, fully independent of the other co-owners’ fates.

For attorneys looking to connect with high-net-worth clients grappling with these exact types of sophisticated planning decisions, Haute Lawyer Network provides an unparalleled platform for visibility and authority. Distinguish your practice by joining our exclusive network. Learn more about how Haute Lawyer Network can elevate your firm.