If you want to trademark your business name, you’ll need to file an application with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The core of the process is proving your name is genuinely unique and that you’re actively using it in commerce. Be prepared for a marathon, not a sprint—it typically takes a good 12 to 18 months from the day you file until your registration is official.

Why Trademarking Your Business Name Matters

Before getting bogged down in the legal paperwork, let’s talk about what’s really at stake. Trademarking transforms your business name from a simple label into a powerful, legally protected asset. It’s how you formally claim ownership over your brand identity on a national level.

Many entrepreneurs mistakenly believe that forming an LLC or incorporating their business is the same as getting a trademark. It’s not. Registering your business with the state only prevents another company in that same state from using your exact legal name. It offers zero protection against a competitor in another state launching with a confusingly similar name.

A federal trademark, on the other hand, grants you exclusive rights across all 50 states.

Differentiating Your Intellectual Property

It’s crucial to understand the different tools in the intellectual property (IP) toolbox. Each one serves a distinct purpose, and using the right one ensures you’re protecting the right asset. Our separate guide on how to protect intellectual property offers a much deeper dive into these concepts.

To put it simply:

- Trademarks protect brand identifiers—think names, logos, and slogans that distinguish your goods or services from everyone else’s.

- Copyrights protect original creative works, like your website copy, articles, photographs, and software code.

- Patents protect inventions, giving an inventor exclusive rights to their creation for a set period.

For your business name, a trademark is the right move. Think of Nike’s iconic “swoosh” or the name “Coca-Cola”—these are powerful trademarks that instantly bring a specific source and level of quality to mind for consumers.

A registered trademark is more than a defensive shield; it’s an offensive tool that builds equity. It provides the legal standing needed to stop infringement, secure your brand on social media platforms, and can significantly increase your company’s valuation during a sale or merger.

Understanding Your Brand Protection Options

To make sure you’re pursuing the right legal protection for your business assets, it helps to see how they compare side-by-side.

| Protection Type | What It Protects | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Trademark | Brand names, logos, slogans, and other source identifiers | Protecting your brand identity and preventing consumer confusion in the market. |

| Copyright | Original works of authorship (art, literature, music, code) | Securing ownership of creative content like blog posts, photos, and software. |

| Patent | Inventions, processes, and unique designs | Granting exclusive rights to a new machine, chemical compound, or algorithm. |

Choosing the correct IP protection from the start saves immense time and resources, ensuring your most valuable assets are properly secured.

The Tangible Value of a Trademark

Beyond just legal protection, a registered trademark adds real, measurable value to your business. The global marketplace certainly recognizes this; recent data shows global trademark applications have hit an estimated 11.7 million. This surge underscores just how critical it is for businesses to secure their names early, especially in key markets.

Proactive registration not only safeguards your brand but also boosts its valuation. Trademarked brands often command much higher premiums in mergers and acquisitions. It’s a clear signal to competitors that your brand is off-limits and tells customers you’re a serious, established presence in your industry.

Ultimately, trademarking your business name is a strategic decision. It secures your current market position while laying a solid foundation for future growth and expansion.

Conducting a Thorough Trademark Search

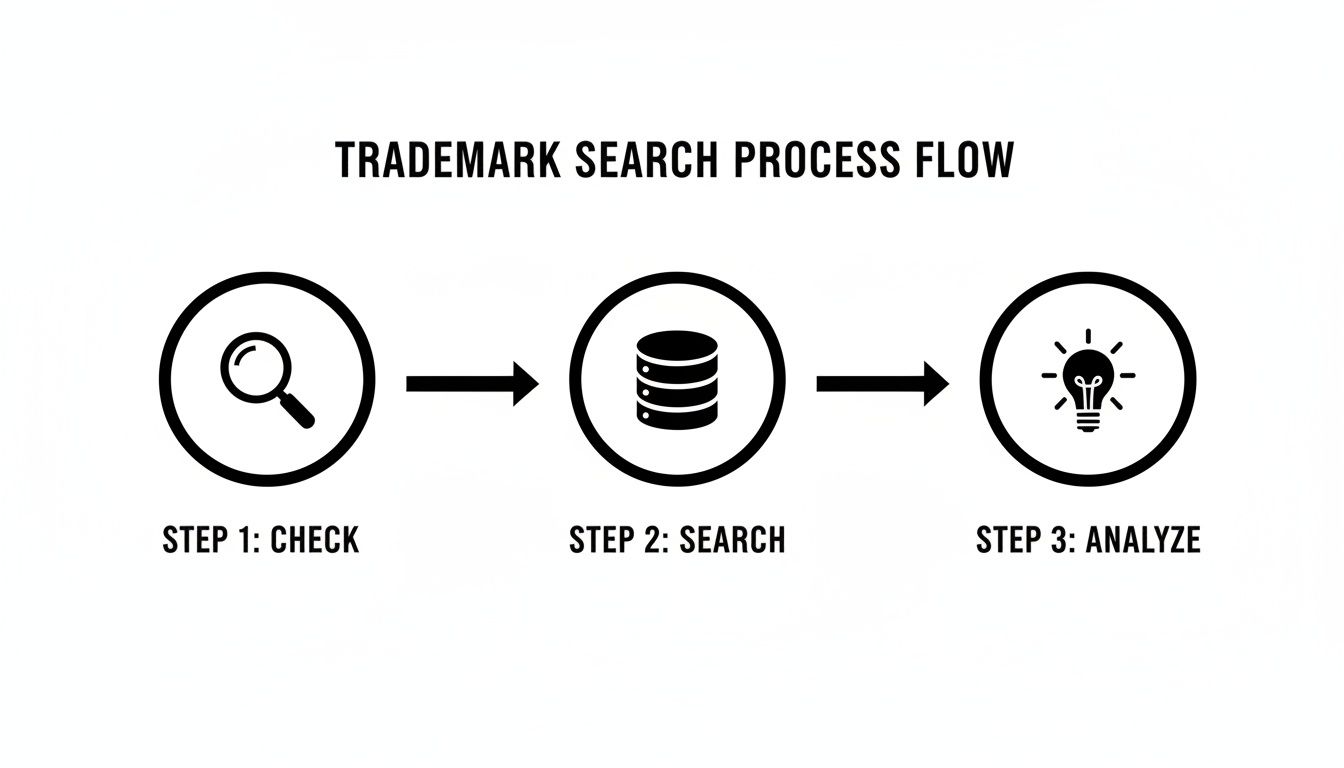

Before you commit a single dollar to an application, you have to do your homework. A comprehensive trademark search is arguably the most critical step in the entire process. Get this wrong, and you’re looking at a costly rejection from the USPTO and a painful, expensive rebrand.

This isn’t about finding exact duplicates. The real goal is to uncover any name an examining attorney at the USPTO could deem “confusingly similar” to your own.

Start where your customers would: Google. A simple online search is your first reality check. Look for your exact name, but don’t stop there. You need to search for common misspellings, phonetic equivalents, and creative variations. If your name is “Kwik Fix,” you absolutely must search for “Quick Fix,” “Kwik Phix,” and even “Quick Fiks.”

This initial sweep should also include social media platforms, domain registries, and state business filings. If another company is already using a similar name in a related industry, consider it a major red flag.

Diving into the USPTO TESS Database

Once you’ve cleared the initial online hurdles, it’s time to get official. The USPTO’s Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS) is the definitive database for all registered and pending federal trademarks. Be warned: its interface is powerful but not exactly user-friendly for newcomers.

Here are a few practical tips to get you started on TESS:

- “Basic Word Mark Search (New User)” is your starting point for checking exact matches. It’s the most straightforward option.

- “Word and/or Design Mark Search (Structured)” is where the real work begins. It lets you use search operators like “AND” or “OR” and wildcards (like using a “$” to find plural or alternative word endings).

- Search for phonetic similarities. Trademark law protects against auditory confusion, meaning names that sound the same can be in conflict. TESS has tools for this, and you need to use them.

You have to think like a USPTO examiner. They’re not just looking for identical marks used for identical products. They are assessing whether your proposed name, used for your specific goods or services, could make a consumer think it’s connected to an existing brand.

Beyond the Federal Database

Here’s a common and costly mistake: assuming the TESS search is the end of the road. In the United States, trademark rights can be established simply by using a name in commerce, a concept known as “common law” trademarks. These rights exist even without a federal registration.

This means your search has to expand to find unregistered businesses that were using a similar name before you. That search should include:

- Industry-specific directories and trade publications.

- Deeper dives into social media and online marketplaces.

- Lists of exhibitors from major trade shows in your field.

Failing to uncover an established common law user can land you in serious legal trouble, even if your federal trademark application sails through. This is where the guidance of an experienced intellectual property attorney becomes indispensable. They have access to professional-grade search tools that comprehensively cover federal, state, and common law sources far more effectively than a DIY search can.

Key Takeaway: A proper trademark search is a multi-layered investigation. It combines federal database queries with deep, real-world market research to ensure the name you love is actually available for you to own and defend.

Ultimately, the distinctiveness of your name is what matters most. Generic or descriptive terms face rejection rates of over 50% worldwide. In fact, comprehensive analyses often show that 20-30% of all proposed names have direct conflicts with prior marks. Diligence now prevents a legal and financial nightmare later. You can find more trademark filing trends and statistics from Clarivate to see just how competitive the landscape is.

Preparing Your USPTO Trademark Application

With a solid trademark search behind you, it’s time to translate your brand into the formal language of a United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) application. This isn’t just paperwork—filing your application is a critical moment. Getting it right the first time can save you months of delays and hundreds of dollars in unnecessary fees.

The entire process is handled online through the Trademark Electronic Application System (TEAS). This is the USPTO’s official portal where you’ll define every detail about your mark, from its design to the specific goods or services it represents.

Choosing Your Application Form: TEAS Plus vs. TEAS Standard

Your first decision inside the TEAS portal is which application to use. The USPTO offers two paths, each with different rules and costs.

- TEAS Plus: This is the most cost-effective option, with a government filing fee of $250 per class of goods or services. The trade-off for the lower price is stricter requirements. You must choose your goods and services from the USPTO’s pre-approved list in the Trademark ID Manual and agree to all communication via email.

- TEAS Standard: At $350 per class, this form offers more flexibility. It’s the right choice if your offerings are unique and you need to write a custom description because nothing in the pre-approved manual quite fits your business.

For most businesses with straightforward products or services, TEAS Plus is the smarter move. It’s cheaper and significantly reduces the risk of a trademark examiner questioning your descriptions, since they’re already accepted by the USPTO.

This process highlights a key truth: a successful filing is always built on a foundation of comprehensive checks, deep searches, and careful analysis of potential conflicts.

Defining Your Goods and Services Correctly

One of the most common—and damaging—mistakes an applicant can make is getting the description of their goods and services wrong. You have to be precise, because your trademark protection only extends to the specific items you list on the application.

Think of it like this: if you sell t-shirts, you can’t just list “clothing.” You need to specify “T-shirts” under International Class 025. If you’re a business consultant, “business services” is too broad. You’d need something specific like “Business management consulting” under International Class 035.

A vague or incorrect description can lead to an outright rejection or, even worse, a registered trademark that doesn’t actually protect the core of your business. For complex or niche industries, professional guidance is invaluable. You can learn more about what separates an expert by exploring a curated network for a top-tier trademark attorney who handles these filings daily.

Submitting a Proper Specimen of Use

A “specimen” is simply your proof that you’re actually using the business name in commerce. It’s a real-world example of how your customers see your brand in action. What counts as a good specimen depends entirely on whether you sell goods or provide services.

For Goods (Products): Your proof must show the trademark directly on the product or its packaging.

- Good Example: A clear photo of a clothing tag with your brand name on a shirt you sell.

- Bad Example: A magazine ad for that shirt. Advertisements are not acceptable specimens for goods.

For Services: Your proof must show the trademark being used while selling or advertising the service.

- Good Example: A screenshot of your website’s main banner where services are offered under your brand name.

- Bad Example: A business card or company letterhead. These just identify your business; they don’t show the mark being used to actively sell a service.

Expert Tip: The goal is to show the examiner a clear, undeniable link between your trademark and what you’re selling. They need to see exactly how a customer would connect your name with your offerings in the marketplace.

Filing Basis: “In Use” vs. “Intent to Use”

Finally, you have to declare your filing basis. This tells the USPTO whether you’re already using the mark in business or have firm plans to do so.

- Use in Commerce (Section 1(a)): You file under this basis if you are already selling products or offering services with the trademark across state lines. You’ll need to submit your specimen right away with the initial application.

- Intent to Use (Section 1(b)): This is for entrepreneurs who have a legitimate, good-faith intention to use the mark soon but haven’t launched yet. It lets you reserve your place in line. You won’t submit a specimen at first, but you’ll have to file one later (and pay an extra fee) before the trademark can officially register.

Choosing the right basis is a strategic move. Filing an “Intent to Use” application can secure an earlier priority date, which can be a lifesaver if a competitor suddenly appears. However, it does add an extra step and cost to the process down the road.

Choosing Between Federal and State Registration

After you’ve done your homework and cleared your name, you’ll hit a critical fork in the road. It’s a decision that will define the very scope of your brand’s legal protection: Should you register your trademark federally with the USPTO, or is a simple state-level registration enough?

This isn’t just a matter of paperwork; it directly dictates how far your rights extend and how fiercely you can defend your brand.https://www.youtube.com/embed/VlzYUPrnetQ

For the vast majority of businesses today, a federal trademark registration is the only logical choice. If you operate across state lines in any capacity—and that includes virtually any business with a website selling to customers in another state—federal protection is non-negotiable. It provides a level of security that a state filing can’t even begin to approach.

A federal trademark gives you the exclusive right to use your business name across the entire country. Think about that. You can stop a competitor in Oregon from using a confusingly similar name, even if your company is based in Florida. It also creates a public, official record of your ownership, which is a massive deterrent to would-be infringers.

The Power of Federal Protection

A federal trademark from the USPTO isn’t just a certificate to hang on the wall; it’s a powerful arsenal of legal rights. These protections are built for any business with a national footprint or even just the ambition to grow beyond its local neighborhood.

Here’s what you actually get with a federal registration:

- Nationwide Priority: You lock in exclusive rights to your mark across all 50 states, no matter where your headquarters is.

- Legal Presumption of Ownership: In court, your federal registration is considered prima facie evidence that you own the mark and that the trademark is valid. This is a huge advantage in a dispute.

- Access to Federal Courts: It unlocks the door to federal court, giving you the ability to sue infringers and seek more significant damages.

- Use of the ® Symbol: You earn the right to use the coveted ® symbol. This is a clear signal to the world that your brand is federally protected and you will defend it.

- Blocking Imports: You can record your registration with U.S. Customs and Border Protection to stop counterfeit and infringing goods at the border.

A federal trademark is both a shield and a sword. It shields your brand identity coast-to-coast and gives you the legal weapon you need to proactively enforce your rights against anyone trying to ride your coattails.

When a State Registration Might Suffice

While federal registration is the undisputed gold standard, a state-level trademark can be a reasonable first step for a truly local business with zero plans to expand. We’re talking about a single-location coffee shop, a plumber who only serves one county, or a neighborhood bakery with a purely local customer base.

A state trademark is extremely limited. It only protects your business name within that specific state’s borders. While it’s generally cheaper and faster to get, it offers zero protection against a company in the next state over using the exact same name.

This narrow scope makes it a gamble for any business operating online. The second you sell a single product or service to a customer in another state, you’re engaging in interstate commerce, and your state-level protection is suddenly inadequate.

To make this choice clearer, let’s break down the key differences side-by-side.

Federal vs. State Trademark At a Glance

| Feature | Federal Trademark (USPTO) | State Trademark |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic Scope | Nationwide protection across all 50 states and U.S. territories. | Limited to the borders of the single state where it is registered. |

| Legal Presumption | Strong legal presumption of ownership and validity in federal court. | Limited presumption of ownership, valid only in that state’s courts. |

| Symbol | Allows use of the registered trademark symbol (®). | Only allows use of the unregistered trademark symbol (™). |

| Enforcement | Can sue for infringement in federal court, with access to statutory damages. | Can only sue in state court, with remedies limited by state law. |

| Online Commerce | Essential for any business that sells goods or services online across state lines. | Inadequate for e-commerce; provides no protection against out-of-state competitors. |

| Deterrent Effect | Appears in national USPTO database, deterring others from choosing similar names. | Only appears in a state-level database, which is often missed by others. |

| Cost & Timeline | More expensive and takes longer to process (9+ months). | Less expensive and typically faster to process (a few months). |

Ultimately, choosing federal registration isn’t just a cost—it’s an investment in your brand’s future. It ensures your name is protected as your business grows from a local favorite into a national powerhouse.

What Happens After You File Your Application

Hitting “submit” on your application is a huge milestone, but it’s really just the start of the journey. Now comes the waiting game. Your application goes into the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) queue, where it will sit for several months before an examining attorney even looks at it.

Right now, that initial wait can easily stretch 8 to 10 months, sometimes even longer if there’s a backlog. During this time, your only job is to be patient and keep a close eye on your inbox. The USPTO communicates almost exclusively via email, so make absolutely sure their messages aren’t getting buried in your spam folder.

Navigating the Examination Process

Once an examining attorney finally gets to your file, they’ll give it a thorough once-over to make sure it meets all the legal requirements. This isn’t just a rubber stamp—they conduct their own independent search for conflicting marks and scrutinize every detail, from your description of goods and services to the specimen you submitted.

After this review, one of three things will happen:

- Approval for Publication: This is the best-case scenario. If the examiner finds no issues, your mark gets approved and published in the Official Gazette, a weekly USPTO publication. This kicks off a 30-day window where the public can oppose your registration if they think it harms their own brand.

- Minor Issues: Sometimes, it’s just a small, easily fixable error—a typo or a slight problem with your goods/services description. The examiner might call or email you for a quick fix via an “Examiner’s Amendment.”

- Office Action: If the examiner finds a more serious legal problem, you’ll receive a formal letter called an Office Action. This isn’t a final rejection, but it’s a formal roadblock you have to address.

An Office Action is a standard part of the trademark process, not a reason to panic. It simply means the examiner needs more information or a legal argument from you to move the application forward. Your timely and persuasive response is what matters most.

Responding to an Office Action

Getting an Office Action can feel like a setback, but it’s incredibly common. You’ll generally have six months to file a formal, written response. The most frequent reason for a substantive Office Action is a “likelihood of confusion” refusal, meaning the examiner thinks your mark is too similar to one that’s already registered.

A solid response requires a well-crafted legal argument. You have to explain precisely why your mark is distinct from the one cited, breaking down differences in sound, appearance, and overall commercial impression, as well as the differences in the goods or services. This is where a trademark attorney really earns their keep—crafting these arguments is a specialized skill.

The Long-Term Responsibilities of Trademark Ownership

Securing your registration is a massive win, but it comes with real, ongoing responsibilities. You are now the official guardian of your brand’s integrity in the marketplace. This means you have to actively monitor for infringement and hit critical deadlines to keep your registration from expiring.

Your ongoing duties will include:

- Monitoring: You must police your mark by keeping an eye out for any new businesses that pop up using a confusingly similar name.

- Maintenance Filings: You have to file a Declaration of Use between the fifth and sixth years after registration, and then file for renewal every ten years after that to prove you’re still using the mark.

- Enforcement: If you spot an infringer, the ball is in your court. You’re responsible for taking action, which usually starts with sending a cease-and-desist letter.

In today’s global market, this vigilance often needs to extend beyond U.S. borders. The Madrid System, for instance, saw approximately 65,000 international trademark applications in 2024, a number that shows just how fast successful brands expand. To stay ahead, you can discover more insights about international trademark filings on WIPO.int.

Your Top Trademark Questions Answered

Even with a roadmap, the practical side of trademarking can feel daunting. You’re likely wondering about the real-world costs, timelines, and strategic choices that lie ahead. Let’s cut through the noise and tackle the questions I hear most often from business owners.

Getting clear on these details from the start is about more than just satisfying curiosity—it’s about setting a realistic budget, managing your expectations, and making smart decisions to protect your brand for the long haul.

How Much Should I Budget to Trademark My Business Name?

There’s no single price tag. The total investment is a blend of mandatory government fees and, ideally, professional legal fees.

First up are the government filing fees paid directly to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Right now, you can expect to pay between $250 and $350 per class of goods or services. If you sell apparel (Class 025) and also run a retail website (Class 035), you’re paying for two classes. It adds up.

Then there’s the cost of hiring a trademark attorney. Think of this not as an expense, but as an investment in getting it right the first time. Legal fees for a professional search and application can run from $500 to over $2,000, depending on the complexity. For a relatively straightforward application with expert legal help, a realistic all-in budget often starts around $1,500.

How Long Does the Trademark Process Actually Take?

Patience isn’t just a virtue here; it’s a requirement. From the day you file to the moment you hold your registration certificate, the entire process typically takes 12 to 18 months. And that’s if everything goes smoothly.

The biggest delay is the initial wait. Due to significant backlogs at the USPTO, it can take 8 to 10 months before an examining attorney even looks at your file. If they issue an “Office Action” (a request for clarification or a preliminary refusal), or if someone opposes your mark after it’s published, that timeline can stretch out much further. The takeaway? Start early.

Can I Trademark a Name if Someone Else Is Already Using It?

Almost certainly not, especially if they were using it first for anything remotely similar to what you offer. This is the core of the “likelihood of confusion” standard—the number one reason trademark applications get rejected. The entire point of trademark law is to prevent customers from mixing up one brand with another.

Even if the name isn’t identical, a similar name in a related field is a non-starter. For example, if “Kwik Koffee” is already trademarked for a chain of coffee shops, your application for “Quick Coffee” for a new cafe is going to be denied. This is precisely why a deep, professional search is the most critical first step you can take.

Do I Really Need to Hire an Attorney?

While you can legally file on your own (pro se), it’s one of the riskiest moves a serious business owner can make. This isn’t just filling out a form; it’s a complex legal proceeding where small mistakes can have huge consequences.

An experienced trademark attorney brings critical advantages:

- A Professional Search: They use sophisticated databases that go far beyond what you can find on Google, uncovering potential state and common law conflicts that could derail your application later.

- A Bulletproof Application: They know exactly how to describe your goods and services to maximize your protection and avoid the common traps that trigger an immediate Office Action.

- Expert Navigation: If the USPTO does push back, an attorney can build a persuasive legal argument to overcome the examiner’s objections—a skill you can’t learn overnight.

Investing in specialized legal counsel upfront is one of the smartest business decisions you’ll make. It dramatically increases your odds of success and saves you from the catastrophic costs of a failed application, a forced rebrand, or a future lawsuit over your name.

Finding the right legal expert is crucial for protecting your brand. The Haute Lawyer Network is a curated platform that connects you with top-tier attorneys across the United States, each selected for their professional excellence. Elevate your brand’s protection by exploring our network at Haute Lawyer Network.