To ask for a continuance in court, you have to formally request that a scheduled hearing or trial be postponed. This isn’t just a casual ask; it’s a specific legal procedure.

Usually, this is done by filing a written “Motion to Continue” with the court clerk and making sure the other side gets a copy. In a real pinch, like a last-minute emergency, a judge might allow an oral request right there in the courtroom. But no matter how you ask, your request absolutely must be backed by a valid reason—what the legal world calls “good cause.”

What a Court Continuance Actually Means

It’s a common misconception to see a continuance as a sign of a weak case or just a stalling tactic. In practice, it’s a standard, and often critical, tool in the legal process. Think of it less like hitting the pause button to avoid the inevitable and more like a strategic move to ensure justice is served properly.

At its core, a continuance is a formal postponement. The decision rests entirely with the judge, who has to balance your reason for asking against the court’s need to keep cases moving efficiently. The whole system of legal disputes, which you can read more about by understanding what is litigation, is built on procedural fairness, and continuances are a key part of upholding that principle.

The Foundation of Good Cause

You can’t just ask for more time because a court date is inconvenient. Courts are slammed, and judges need a compelling reason—this “good cause”—to justify shuffling their packed dockets. Without it, your request is dead on arrival.

So, what actually counts? A well-timed request is often what’s needed for both sides to be genuinely prepared. Some common justifications that judges will seriously consider include:

- Discovery of new, crucial evidence that just came to light.

- The need to hire an expert witness whose schedule requires more flexibility.

- A true personal emergency, like a sudden hospitalization or a death in the family.

- The unavoidable absence of a key witness or your attorney due to a legitimate scheduling conflict.

These scenarios show the delay isn’t for convenience; it’s essential for a fair trial. A judge is always more inclined to grant a request when it’s obvious the extra time will lead to a more just and complete outcome.

It Is Not a Sign of Weakness

Requesting a continuance should never be seen as an admission that your case is falling apart. More often than not, it’s the complete opposite. Any sharp legal team knows that barreling ahead without a critical piece of evidence or a key witness is a recipe for disaster.

A continuance isn’t a “get out of jail free” card; it’s a request for the time required to build a proper defense or present a complete case. It ensures the outcome is based on facts and preparedness, not on a rushed timeline.

By asking for a continuance, you’re signaling to the court that you take the proceedings seriously and need adequate time to prepare. It shows respect for the process. Frankly, a judge would much rather see a well-prepared professional on the rescheduled date than an unprepared one trying to wing it.

What Counts as a Good Reason to Postpone a Court Date?

To get a judge to agree to a continuance, you can’t just show up with a flimsy excuse. Your reason has to be legitimate and compelling. Judges are trying to balance moving cases along with making sure justice is served, and they’ve heard it all before. They can spot a delay tactic a mile away.

You need to demonstrate what the courts call “good cause.” This means proving there’s a real, unavoidable issue that makes going forward on the scheduled date unfair or flat-out impossible.

When a Key Person Can’t Be There

One of the most solid grounds for a continuance is when someone essential to your case is suddenly and unavoidably absent. We’re not talking about just any witness; this has to be a person whose presence is critical.

Imagine your star witness—the accident reconstruction expert in your personal injury trial—has an emergency appendectomy two days before you’re due in court. Their testimony is the lynchpin of your entire case. Proceeding without them would be disastrous. That’s a textbook example of a valid reason.

A genuine personal emergency that hits you or your attorney is also a strong basis for a request.

- Sudden Illness or Injury: A documented medical crisis for you, your lawyer, or a key witness is a powerful justification. You’ll likely need to back this up with a doctor’s note or other proof.

- Family Emergency: A death in the immediate family or another severe, unexpected crisis is almost always considered good cause for a postponement.

- Unavoidable Scheduling Conflict: This one can be tricky. A pre-planned vacation won’t cut it. However, if your attorney is unexpectedly ordered to appear in a higher court for another case that same day, a judge is far more likely to grant the continuance.

A judge once told me, “Your emergency is not my emergency, but a just outcome is.” That really frames the court’s perspective: the reason has to be so significant that it outweighs the disruption to the court’s calendar and the delay for the other side.

When You Genuinely Need More Time

Sometimes, things happen that are completely out of your control, making it impossible to be ready for court. These situations usually pop up when new information surfaces or you need to wrap up a critical legal step.

For example, let’s say the opposing side drops a mountain of complex financial records on you just a week before trial. You have a very strong argument that you need more time to review and analyze those documents properly. This isn’t about dragging your feet; it’s about having a fair shot.

Strong vs. Weak Excuses

Judges have a finely tuned sense for what’s a legitimate problem versus a weak attempt to stall. Knowing the difference is crucial for framing your request in the best possible light.

| Strong Justification (Likely to be Granted) | Weak Justification (Likely to be Denied) |

|---|---|

| A sudden, documented medical emergency affecting a party or key witness. | A minor, routine doctor’s appointment that could have been rescheduled. |

| New, complex evidence was just handed over by the other side. | A vague claim that “I need more time to prepare” without a specific reason. |

| Your attorney has an unavoidable conflict, like a trial in another court. | A scheduling conflict with a personal vacation or a work meeting. |

| A key witness is unexpectedly out of the country and their absence was a surprise. | You simply forgot about the court date or failed to arrange for time off work. |

At the end of the day, your reason must show the problem was unforeseeable, unavoidable, and critical to your ability to fairly present your case. A request that stems from your own lack of preparation, like waiting until the last minute to hire a lawyer, will almost certainly fail. Your most persuasive angle is always to show you’ve acted responsibly but are now facing an unexpected hurdle.

How to File a Motion to Continue

So, you have a solid reason to postpone your court date. What now? The next step isn’t a quick phone call—it’s preparing a formal legal document called a Motion to Continue. This is your official, on-the-record request to the judge, and getting it right is everything.

Think of this motion as your persuasive argument on paper. It has to be sharp, clear, and backed with proof. The judge likely only has a few minutes to scan your file, so they need to immediately grasp who you are, what you’re asking for, and why you deserve it.

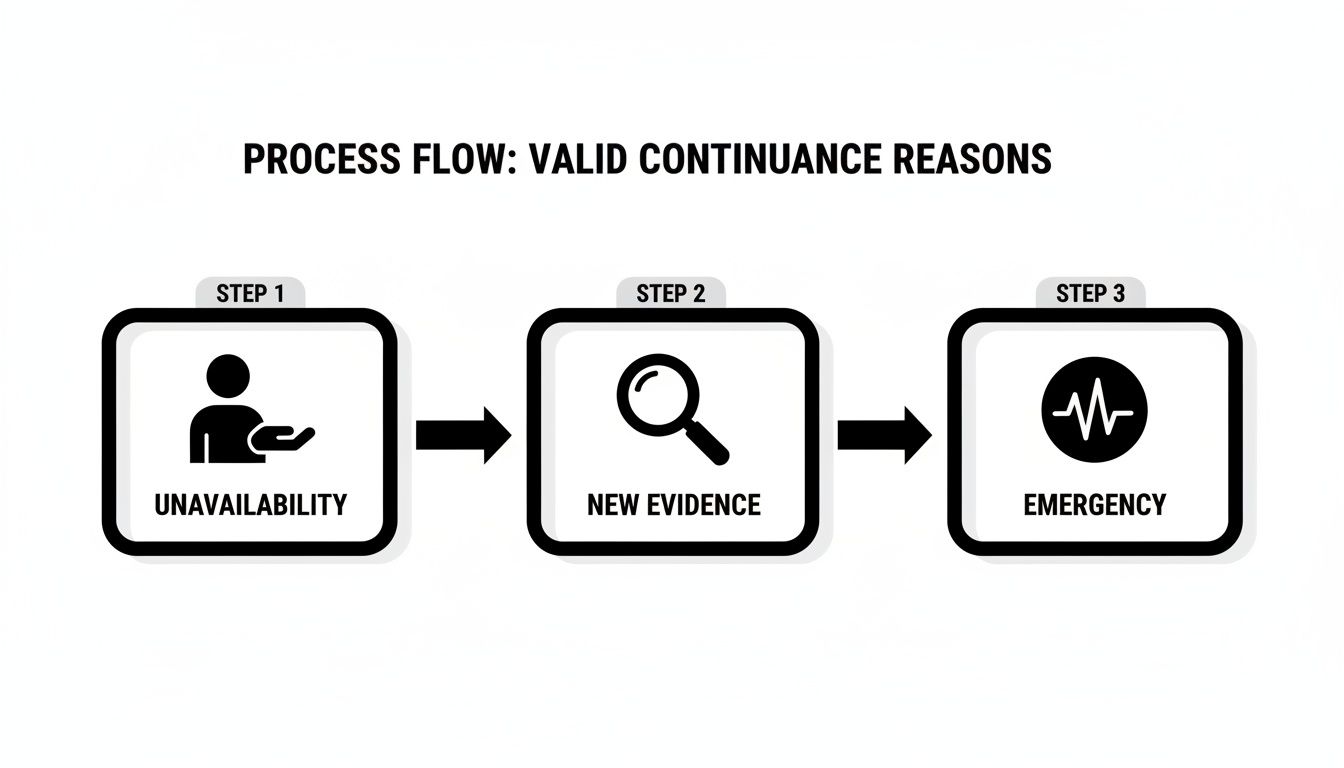

This diagram hits on the big three reasons that usually get a judge’s attention.

As you can see, the strongest arguments involve situations you can’t control. An unavailable witness, a sudden emergency, or surprise evidence popping up—these are things that directly threaten the fairness of the hearing.

Drafting Your Written Motion

A well-crafted motion isn’t just a simple request; it’s a structured argument. While the exact formatting can change from one courthouse to another (always check your local rules), a motion that gets results will always have these core elements:

- A Crystal-Clear Request: Get straight to the point. Start by stating exactly what you want. For example, “Defendant moves to continue the trial currently scheduled for October 26th.” No fluff.

- The Specific Grounds: This is the heart of your motion. Lay out your “good cause” logically and in detail. Whether it’s a sudden medical issue, a key witness being out of the country, or crucial evidence that just came to light, explain the full situation.

- Proof to Back It Up: Don’t just tell the judge you have a reason; show them. Attach copies of anything that proves your claim. This could be a doctor’s note, flight itineraries showing a conflict, or a signed affidavit from that unavailable witness.

- A Proposed New Date: Suggesting one or two potential new dates shows the court you’re being proactive and not just trying to delay for the sake of it. Big bonus points if you’ve already cleared these dates with the opposing party.

Pro Tip: Don’t frame the request around your own convenience. Instead, frame it around the “interests of justice.” A motion asking for time to “ensure a fair trial with all necessary evidence available” sounds a lot better than one that just says, “I need more time.”

Filing and Serving the Motion Correctly

Writing a brilliant motion is only half the battle. If you don’t file and serve it correctly, it’s worthless. This is where a lot of people trip up.

First, you must file the motion with the court clerk. This usually means taking the original document down to the clerk’s office. Many courts have moved to e-filing systems, so check your local court’s website to see if that’s an option—or a requirement.

Next, you have to provide a copy to the other side (or their attorney). This is called “service,” and you can’t just toss it in a mailbox. You have to follow the court’s rules, which often require certified mail or using a professional process server to create a legal record that they received it.

Messing up service is a classic rookie mistake that can get your motion tossed before a judge even lays eyes on it.

When an Oral Request Might Work

While a written motion is the gold standard, there are rare instances where making an oral request in the courtroom might fly. This is reserved for true, last-minute emergencies that pop up right before a hearing.

For example, if you wake up with a raging fever on the morning of your trial, you or your attorney might show up to explain the situation directly to the judge. Or if your star witness gets into a car accident on the way to the courthouse—that’s another scenario where an on-the-spot oral request makes sense.

Deciding between a formal written motion and a last-minute oral request involves weighing several strategic factors.

Written Motion vs Oral Request: A Strategic Comparison

| Consideration | Written Motion | Oral Request |

|---|---|---|

| Timing | Best when you have advance notice (days or weeks). | Only for true, unforeseeable, last-minute emergencies. |

| Formality | High. Creates a formal, written record for the case file. | Low. It’s an on-the-spot request with no prior paperwork. |

| Supporting Evidence | Strong. Allows for attaching documents, affidavits, and exhibits. | Weak. You can only describe the evidence, not present it. |

| Judicial Review | Gives the judge time to review your reasons and the law. | Forces an immediate decision with limited context. |

| Risk Level | Low. This is the professionally accepted, standard procedure. | High. Can be seen as unprofessional or a delay tactic if not justified. |

| Opponent’s Response | Gives the other side a formal chance to object in writing. | Puts the other side on the spot to respond immediately. |

Ultimately, relying on an oral request is a high-risk gamble. It should only be a last resort for truly dire and unexpected circumstances. For any situation where you have even a day or two of notice, the formal written motion is the correct and much safer play.

Handling Objections and Judicial Discretion

Filing your motion for a continuance is a critical move, but don’t mistake it for a guaranteed win. The other side has every right to object—and they often will. You have to be ready to defend your request, not just in your paperwork but potentially face-to-face with the judge.

Even if the other party stays silent, the final call belongs to the judge alone. This is where understanding the delicate dance of legal opposition and the judge’s ultimate authority—known as judicial discretion—can make all the difference.https://www.youtube.com/embed/9u8dfYzIYS8

Anticipating and Countering Objections

The second your motion is filed, you should assume the opposing counsel is preparing a counter-argument. Their job is to keep the case on track for their client, and that almost always means resisting delays. Fortunately, their objections tend to follow a few predictable patterns.

You can expect to hear arguments like:

- “This is just a delay tactic.” This is the classic, go-to objection. They’ll paint your request as a strategic move to stall the case, hoping to frustrate them or weaken their evidence over time.

- “They failed to act with due diligence.” The other side might try to frame the situation as a problem of your own making. For instance, if you need more time to locate a witness, they’ll argue you should have started searching months ago.

- “A delay will prejudice our case.” This is their most powerful weapon. They might claim a postponement will cause them real, measurable harm. Perhaps their key witness is elderly and in poor health, or they’re racking up serious financial losses while the case drags on.

Your job is to dismantle these arguments before they ever gain momentum. The best way to do this is to address them proactively right in your initial motion. If you just received a mountain of discovery documents, state the exact date you got them to prove the delay isn’t your fault. A clear timeline is your best friend.

The most effective way to counter an objection is to shift the focus from what you need to what the case requires for a just outcome. Frame it as a matter of fairness. Emphasize that pushing forward without this extra time would prevent the court from hearing the whole story.

If you have to argue your point in court, stay cool and stick to the facts. Acknowledge that delays are inconvenient but calmly reiterate why this one is essential for justice to be served. A well-reasoned argument always beats an emotional plea.

Understanding the Judge’s Role and Discretion

At the end of the day, the judge holds all the power. This authority is called judicial discretion, and it’s the single most important factor in getting your continuance approved.

Unlike many legal rules with hard-and-fast limits, most courts don’t have a strict cap on the number of continuances you can ask for. As the legal experts at The Cochran Firm explain, this means everything hinges on the strength of your reasoning and the judge’s personal assessment of the situation.

Judges are constantly balancing several factors. They’ll look at the legitimacy of your reason, whether you’ve been diligent, and how a delay might harm the other party. They also have their own incredibly busy dockets to manage.

Factors Influencing a Judge’s Decision:

| Favorable Factors | Unfavorable Factors |

|---|---|

| First continuance request in the case | Multiple prior continuance requests |

| Strong, documented evidence (e.g., doctor’s note) | Vague, unsupported reasons |

| Opposing party agrees to the continuance | Strong, reasoned objection from opposing party |

| Request filed well in advance of the court date | Last-minute, surprise request |

While there’s no magic number, think of judicial patience as a resource you don’t want to exhaust. Your first request for a good reason is usually the easiest to get. Each one after that gets progressively harder. A judge will start to see a pattern and become far less willing to disrupt their calendar for your case.

Your entire approach should be about making it easy for the judge to say yes. Give them a compelling, well-documented reason. Show respect for the court’s time by filing as early as possible. And if you can get the other side to agree to the new date beforehand, you’re in an even stronger position. When you show you’re professional and focused on a fair resolution, you align your goals with the judge’s, which is the surest path to getting the time you need.

Navigating Local Rules and Finding Alternatives

The legal system isn’t one-size-fits-all. It’s a complex patchwork of federal, state, and local jurisdictions, and each courthouse plays by its own set of rules. This is especially true when you need to ask for a continuance. What flies in one county might get your request shot down in the one next door.

Ignoring these local rules is the fastest way to get your motion denied before a judge even reads it. Many courts have specific deadlines, like requiring all motions to be filed at least five business days before a hearing. Some might mandate a specific form or require you to confirm you tried to get the other side’s consent first.

Why the Court’s Calendar Matters

Beyond the written rules, you have to face the practical reality of the court’s schedule. A judge’s willingness to grant a postponement often comes down to the size of their docket. A court buried in cases is going to be far less receptive to delays that just add to its backlog.

Court caseloads can swing wildly. For instance, after civil case filings in U.S. district courts jumped 22 percent in one year, they dropped by the same amount the next, resulting in 76,189 fewer cases. These fluctuations directly impact how flexible a judge can be. Overwhelmed courts tighten their standards for granting continuances just to manage their dockets. You can see these trends for yourself by reviewing the latest federal judicial caseload statistics.

A seasoned attorney will often check the court calendar or even speak with the judge’s clerk to get a feel for how busy things are. This insight helps frame the request in a way that respects the court’s time, making a judge much more likely to listen.

The Power of a Stipulation Agreement

Instead of gearing up for a fight with a formal, contested motion, there’s often a much smarter path: negotiating with the other side. When both parties agree to postpone a court date, this agreement is called a stipulation.

A stipulation is basically a formal pact between you and the opposing party that you present to the judge for a rubber stamp. This collaborative approach is almost always welcomed by the court.

By presenting a united front, you’re not asking the judge to solve your problem; you’re bringing them a solution. This saves everyone time, reduces conflict, and shows you’re both acting reasonably.

Judges appreciate when parties can sort out scheduling conflicts on their own. It shows professionalism and respect for the process, which can build the kind of goodwill that pays dividends later in your case.

How to Negotiate a Stipulation with Opposing Counsel

Approaching the other side for an agreement requires a bit of finesse. Your goal is to make it an easy “yes” for them, getting the extra time you need without burning any bridges.

Here’s a practical way to handle it:

- Reach Out Early. Call the other lawyer as soon as you know you need a continuance. A last-minute request feels like an emergency you created; an early heads-up is a professional courtesy.

- Give a Brief, Legitimate Reason. You don’t need to reveal your entire strategy. Just be concise and credible. “My key witness has an unavoidable surgery scheduled” works much better than a vague “Something came up.”

- Propose Specific New Dates. Do your homework first. Come prepared with two or three potential new dates. It shows you’re organized and serious about moving the case forward, just on a slightly different timeline.

- Offer to Do the Heavy Lifting. Make it simple for them. Offer to draft the stipulation agreement and file it with the court. This small gesture removes work from their plate and makes them far more likely to agree.

Once you have an agreement, you’ll draft a short document called a “Stipulation to Continue,” which simply states that both parties agree to move the hearing from Date A to Date B. You and the opposing counsel both sign it, and then it’s filed with the court. The judge’s final approval is usually just a formality at that point. This approach is often simpler than other legal deferrals, though our traffic ticket deferral guide shows how similar concepts work in other contexts.

Common Questions About Court Continuances

Trying to postpone a court date naturally brings up a lot of questions. Let’s cut through the noise and get straight to what you need to know.

What Happens If My Continuance Request Is Denied

If the judge says no, that’s it—the court date stands. You are legally required to be there and ready to proceed.

Failing to appear is not an option. It can lead to a default judgment against you in a civil matter or, even worse, an arrest warrant in a criminal case. It’s critical to have a plan B. If a denial is a real possibility, you and your attorney should have already discussed how you’ll handle it.

How Far in Advance Should I Ask for a Continuance

The moment you know you need a delay, act. Filing your request well in advance shows the court you respect its time and the opposing party’s schedule. It proves you aren’t just trying to cause last-minute chaos.

Most courts have local rules requiring continuance motions to be filed at least 5-10 business days before the hearing. A request filed at the eleventh hour is almost always denied unless you have a true, unavoidable emergency, like being hospitalized the morning of your trial.

Waiting until the last minute without an ironclad reason is a recipe for failure.

Can the Other Party Object to My Request

Yes, and you should probably expect them to. The other side has every right to oppose your motion for a continuance.

They might argue that you’re just using it as a delay tactic, that you haven’t shown “good cause,” or that the delay will actively prejudice their case. For instance, they could claim a key witness is scheduled to move out of the country and won’t be available for a later date. This is exactly why your initial request must be built on a strong, well-documented foundation—it’s your best defense against any objections.

Do I Need a Lawyer to Request a Continuance

Legally, no. You can file for a continuance yourself—this is called appearing “pro se.” Practically, it’s a bad idea. The legal system is a minefield of written rules and unwritten customs that are incredibly difficult for a non-lawyer to navigate successfully.

An experienced attorney brings several immediate advantages to the table:

- Knowledge of Local Rules: They already know the specific deadlines, formatting, and filing procedures for your particular courthouse.

- Understanding “Good Cause”: They know which arguments the local judges find compelling and which ones they dismiss out of hand.

- Professional Motion Drafting: A lawyer can write a formal, persuasive motion that anticipates and neutralizes potential objections before they’re even raised.

- Negotiation Skills: Often, a skilled attorney can simply call the opposing lawyer and agree to a continuance, avoiding a contested court hearing entirely.

The question of representation comes up frequently, especially in traffic matters. You can explore whether you might need a lawyer for traffic court in our detailed breakdown. In short, having an attorney dramatically improves your odds of success.

When facing complex legal proceedings, having an elite legal professional in your corner is invaluable. The Haute Lawyer Network connects you with a curated selection of the nation’s top attorneys, each recognized for their excellence and professional integrity. Find the expert legal guidance you need by exploring our network at https://hauteliving.com/lawyernetwork.