Let’s cut right to the chase: In most situations, your workers’ compensation settlement is not taxable at the federal or state level. The IRS doesn’t typically see money meant to compensate you for a physical injury as “income,” which means the full amount is yours to keep.

Your Guide to Workers Comp Settlement Taxes

When you’re recovering from a workplace injury, the last thing you want to worry about is a surprise tax bill. The most common question we hear is, “Is my workers’ comp settlement taxable?” For most people, the answer is a welcome relief. The government’s view is that these funds are designed to make you financially “whole” again after an injury, not to make you rich.

This isn’t just a guideline; it’s baked into federal law. According to Internal Revenue Code §104(a)(1), payments received for personal physical injuries or sickness are excluded from gross income. This rule has been around for a long time and covers both the weekly checks you might get and any lump-sum settlement you agree to. As long as the money is clearly for medical bills or lost wages stemming from that physical injury, you won’t report it as income to the IRS. For a deeper dive into how lump-sum settlements are treated, you can find great insights on their taxability from Amicus Planners.

What Parts of a Settlement Are Tax-Free?

It’s crucial to know exactly what parts of your settlement are shielded from taxes. The tax-free portions are always directly tied to the physical and financial fallout from your injury.

Typically, this includes money for:

- Medical Expenses: Every dollar meant to reimburse you for doctor visits, surgeries, prescriptions, and physical therapy is tax-free.

- Lost Wages: The portion of your settlement that makes up for the paychecks you missed while recovering is also protected.

- Permanent Disability: Payments for any lasting physical impairment are considered non-taxable.

The entire point of workers’ comp is to act as a financial safety net for injured employees and their families. Slapping a tax on these critical funds would completely undermine the system’s purpose.

Quick Breakdown of Taxable vs. Nontaxable Components

While the core of your settlement is usually safe, some specific elements can trigger a tax liability. Knowing the difference is key to avoiding headaches later.

To make things simple, here’s a table that breaks down which parts of a settlement are generally taxable and which aren’t at the federal level.

Taxability of Workers’ Comp Settlement Components

| Settlement Component | Federal Tax Status | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Expense Payments | Nontaxable | This is a direct reimbursement for a loss you incurred, not income. |

| Lost Wages (from injury) | Nontaxable | It’s classified as compensation for a physical injury under the law. |

| Punitive Damages | Taxable | This is considered income because it’s meant to punish the employer, not compensate you for a loss. |

| Settlement Interest | Taxable | The IRS treats this just like interest you’d earn from a savings account—it’s investment income. |

| Emotional Distress (no physical injury) | Taxable | For emotional distress payments to be tax-free, they must directly result from a physical injury. |

The main takeaway here is that as long as your settlement is clearly designated for medical costs and lost wages due to a physical injury, you are on solid ground. It’s when other elements get mixed in that the tax situation can get more complicated.

Why the IRS Views Your Settlement Differently

It seems almost counterintuitive, doesn’t it? Receiving a large sum of money from a settlement that isn’t considered taxable income by the IRS. But the government’s reasoning is surprisingly logical. They don’t see it as a lottery win; they see it as making things right.

Think of it like this: your classic car gets damaged in an accident that wasn’t your fault. The other driver’s insurance pays $5,000 for the repairs. That money isn’t a profit for you. It’s the exact amount needed to restore your car to its pre-accident condition—to make you financially whole again. You haven’t gained a thing; you’ve just been put back where you started.

The IRS applies this very same “make-whole” logic to your workers’ comp settlement. A workplace injury damaged your health and your ability to earn a living. The settlement is the financial equivalent of repairing that damage.

The Legal Bedrock: The Make-Whole Doctrine

This isn’t just a casual IRS policy; it’s a foundational principle of U.S. tax law known as the “make-whole doctrine.” Its legal roots are planted firmly in the tax code itself.

Internal Revenue Code §104(a)(1) explicitly states that gross income does not include “amounts received under workmen’s compensation acts as compensation for personal physical injuries or physical sickness.”

This single, powerful sentence is the legal shield that protects your settlement for medical bills and lost wages. The law acknowledges that these payments aren’t a financial gain but a restoration of your physical and economic well-being. This isn’t a uniquely American concept, either. Many developed nations, including Canada and parts of Western Europe, also exempt core workers’ comp benefits from tax, reflecting a global understanding of their restorative purpose. You can find more essential IRS insights on Hauteliving.com.

Grasping this core idea is the key to understanding why the answer to “is a workers’ comp settlement taxable?” is usually no. It sets the stage for the entire conversation, explaining why some parts of a settlement are tax-free while others—those that go beyond just making you whole—might not be.

Compensation Versus Windfall

So, where does the IRS draw the line? It all comes down to a simple distinction: is a payment meant to compensate you for a loss, or is it something more? The tax-free status applies strictly to payments that cover direct losses from a physical injury.

These almost always include:

- Medical Treatment: Money to cover every doctor’s visit, surgery, and prescription related to your injury, both past and future.

- Lost Earning Capacity: Funds to replace the wages you couldn’t earn because of your physical limitations.

- Physical Pain and Suffering: Compensation for the actual physical hardship you went through.

The moment a settlement includes elements that go beyond this restorative purpose, the IRS changes its tune. For instance, punitive damages—which are designed to punish the employer, not compensate you—are viewed as an additional financial gain. That’s why they become taxable income, a critical difference we’ll explore next.

Identifying the Taxable Parts of Your Settlement

While the core of your workers’ comp settlement is generally protected from the IRS, not every dollar you receive is automatically shielded. The central idea is the “make-whole” principle—payments meant to restore you after a physical injury aren’t considered income.

But think of your settlement like a contract. The main terms cover your medical care and lost wages, which are tax-free. However, a few specific clauses or add-ons can be mixed in, and it’s these elements that the government wants a piece of. Understanding these exceptions is crucial for avoiding a nasty surprise come tax season.

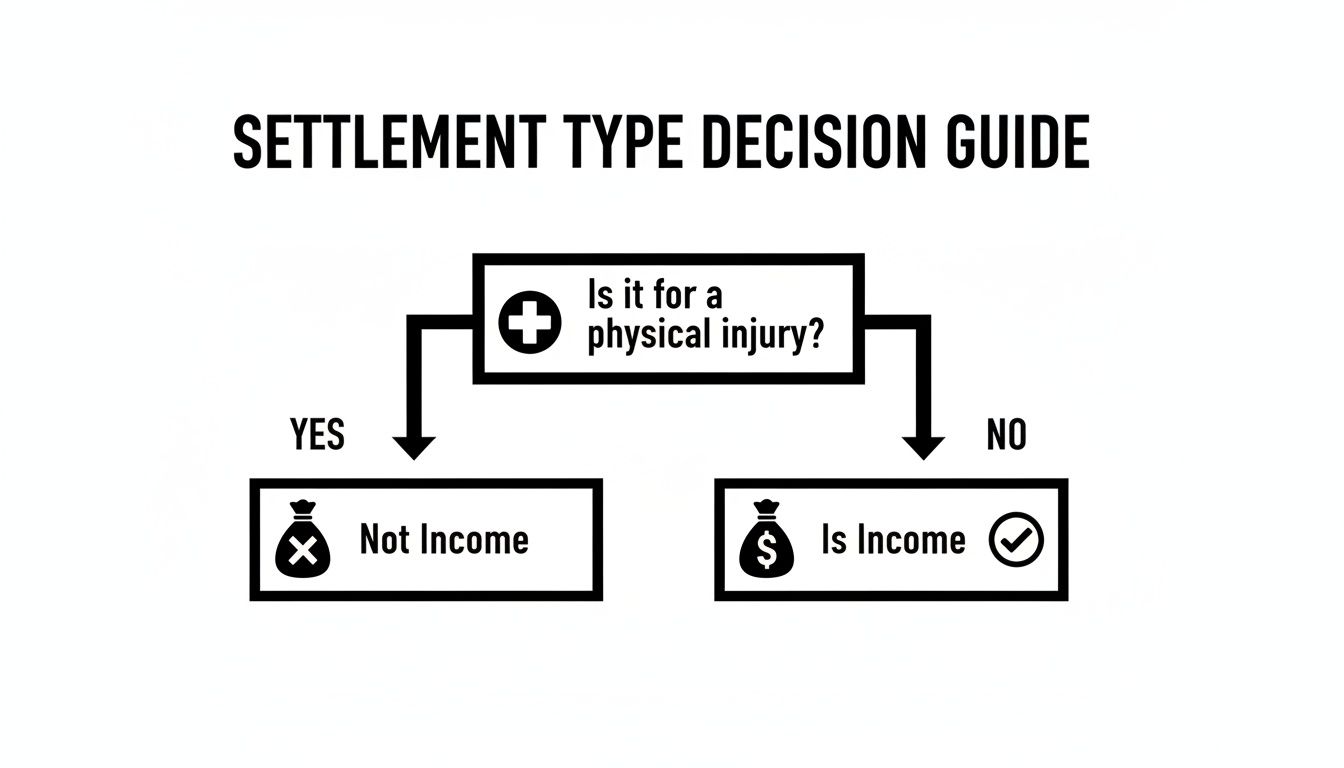

This simple decision tree helps visualize the basic rule: if a payment is for a physical injury, it’s generally not considered income.

The flowchart makes it clear: the nature of the payment is what the IRS cares about. Let’s break down the specific components that fall on the taxable side of that line.

Punitive Damages Are Always Taxable

One of the most significant taxable components is punitive damages. These aren’t designed to compensate you for your injury or lost wages. Instead, they’re awarded to punish an employer for extreme negligence or intentional misconduct.

Because the purpose of punitive damages is punishment rather than restoration, the IRS sees this money as a financial windfall. It’s considered income, plain and simple, and must be reported on your tax return. While rare in standard workers’ comp cases, they can appear in related civil lawsuits filed alongside your claim.

Interest Earned on Your Settlement

Sometimes, a settlement isn’t paid out right away. If there are delays in the process, your final payment might include an additional amount for accrued interest. That interest is taxable.

The IRS treats this exactly like interest earned from a bank savings account. It’s considered investment income, not compensation for your injury. You will likely receive a Form 1099-INT from the payer, detailing the exact amount of interest you need to report.

The rule is straightforward: any money your settlement earns for you in the form of interest is taxable. The original settlement principal meant for your injury remains tax-free, but the growth it generates does not.

When Emotional Distress Becomes Taxable

This is where things can get tricky. Compensation for emotional distress can be either taxable or tax-free, and it all comes down to the source.

- Nontaxable: If your emotional distress—like anxiety or PTSD—is a direct result of your physical workplace injury, any related compensation is generally tax-free.

- Taxable: If a portion of your settlement is for emotional distress that is not directly tied to a physical injury, that amount is considered taxable income.

The specific language in your settlement agreement is critical here. It must clearly link any emotional distress damages to the physical harm you suffered to keep them in the non-taxable category. Navigating these complexities often requires careful legal strategy, as there can be many hidden costs of personal injury if not handled correctly.

While the general answer to “is my workers’ comp settlement taxable?” is no, these exceptions demand careful attention. Scrutinizing your agreement for punitive damages, interest payments, or vaguely defined emotional distress claims is the best way to prepare for your tax obligations.

How Other Benefits Can Affect Your Taxes

While the federal government has a pretty straightforward rule for workers’ comp, things can get complicated once other benefits enter the picture. The simple answer to “is workers’ comp taxable?” starts to blur when we look at how state laws and other government programs—especially Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)—interact.

Think of your benefits as separate streams of income. Most of the time, they flow on their own. But when the workers’ comp stream merges with the Social Security stream, the combined flow can trigger an overflow—and that overflow can create some unexpected tax problems.

State Tax Laws Are Usually Consistent

For the most part, states follow the federal government’s lead. If your workers’ compensation settlement is tax-free at the federal level, it’s almost certain to be tax-free at the state level, too. This consistency simplifies things for the vast majority of injured workers.

But “most” isn’t “all.” It’s always a smart move to double-check your specific state’s tax laws or talk to a local tax pro, as some states have unique rules. For business owners, staying on top of these nuances is critical, and you can master employment law for employers by keeping informed on these very details.

The Social Security Disability Offset Explained

The biggest—and most misunderstood—exception is the Social Security Disability (SSDI) offset. This rule only kicks in if you’re receiving both workers’ comp and SSDI benefits at the same time. The Social Security Administration (SSA) has a cap on the total amount of disability benefits a person can receive from government programs.

Here’s the rule of thumb: Your combined workers’ comp and SSDI payments cannot be more than 80% of your “average current earnings” from before you were disabled.

If your total benefits push you over that 80% threshold, the SSA will “offset” (meaning, reduce) your SSDI payments to bring the total back down to the limit. And that’s exactly where the tax problem starts.

The portion of your workers’ comp benefit that effectively causes your SSDI benefit to be reduced can become taxable. The IRS sees this amount as replacing taxable Social Security income, so it gets taxed just the same.

This is a common trap that catches many people off guard. It’s easy to assume all workers’ comp is tax-free, but when SSDI is involved, a portion of your benefits can suddenly appear on your tax bill. Depending on your prior earnings, this can lead to thousands of dollars in unexpected taxable income each year.

A Practical Example of the SSDI Offset

Let’s break it down with a real-world scenario. Meet Alex:

- Average Pre-Injury Earnings: $5,000 per month

- SSDI Benefit: $2,200 per month

- Workers’ Comp Benefit: $2,500 per month

1. Calculate the 80% Limit: First, the SSA figures out Alex’s 80% earnings threshold.

- $5,000 (average earnings) x 0.80 = $4,000

- This is the absolute maximum Alex can receive in combined benefits.

2. Add the Current Benefits: Next, we total up what Alex is actually getting.

- $2,200 (SSDI) + $2,500 (Workers’ Comp) = $4,700

3. Determine the Offset: Now, we find the difference between Alex’s total benefits and the 80% limit.

- $4,700 (Total Benefits) – $4,000 (80% Limit) = $700

- This $700 is the “offset” amount—the excess.

4. Apply the Reduction: The SSA will reduce Alex’s SSDI check by that offset.

- $2,200 (Original SSDI) – $700 (Offset) = $1,500 (New SSDI Payment)

And here’s the tax punchline: The $700 portion of Alex’s workers’ comp payment is now considered taxable income. Even though it comes from a typically tax-free source, the IRS reclassifies it because it displaced taxable SSDI dollars. Alex now has to report and pay taxes on that $700 every month, which adds up to $8,400 a year.

Example of SSDI Offset Calculation and Tax Impact

This table provides a clear, step-by-step breakdown of how the SSDI offset is calculated using Alex’s numbers and shows exactly where the tax liability comes from.

| Calculation Step | Example Amount | Tax Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Average Pre-Injury Earnings | $5,000 / month | N/A (Basis for calculation) |

| 80% Earnings Limit | $5,000 x 0.80 = $4,000 | This is the maximum non-taxable threshold. |

| Total Combined Benefits | $2,200 (SSDI) + $2,500 (WC) = $4,700 | The total exceeds the 80% limit. |

| Calculate the Offset | $4,700 – $4,000 = $700 | This is the excess amount. |

| New Reduced SSDI Benefit | $2,200 – $700 = $1,500 | The SSDI payment is lowered. |

| Taxable Portion of WC | $700 / month | This part of the WC benefit is now taxable. |

As you can see, what starts as a simple, tax-free benefit can become complicated. It’s crucial for anyone receiving both workers’ comp and SSDI to understand this interaction to avoid a surprise tax bill.https://www.youtube.com/embed/MBRzFX5t5z0

Why the Wording of Your Settlement Matters

When it comes to your workers’ compensation settlement, words aren’t just words—they’re money. The specific language used in your settlement agreement can be the difference between a completely tax-free payment and an unexpected, painful bill from the IRS.

A poorly drafted document leaves the door wide open for interpretation, which is a risk you simply cannot afford to take. Think of it this way: if your settlement is just one big, unlabeled bucket of cash, the IRS gets to decide what it’s for. But if it’s carefully divided into smaller, clearly labeled buckets—”medical,” “lost wages”—there’s nothing left to guesswork.

Precision isn’t just a preference here; it’s a financial necessity. Vague language creates ambiguity, and ambiguity is the IRS’s playground.

The Power of Precise Allocation

A settlement agreement that just states a payout of a “$150,000 lump sum” is a massive red flag for tax trouble. It fails to specify why you are receiving those funds. Without that clarity, the IRS could easily argue that some portion of it is for something other than your direct physical injury, potentially making it taxable income.

On the other hand, a well-drafted agreement provides a detailed breakdown, leaving no room for doubt. This practice is known as allocation.

A strong, tax-optimized agreement would allocate the funds with total specificity:

- $100,000 for future medical expenses related to the workplace injury.

- $50,000 as compensation for past and future lost wages due to physical inability to work.

This detailed allocation creates a paper trail that directly links every dollar to its non-taxable purpose under IRC §104(a)(1). It tells the IRS exactly how to classify the funds, protecting your settlement’s tax-free status and shielding you from future disputes or audits. The goal is to define the terms proactively, not react to an IRS inquiry later.

Your settlement document is your primary defense in a tax audit. Clear, specific language that explicitly allocates funds to medical care and lost wages from a physical injury is the strongest shield you have.

The Attorney’s Critical Role in Structuring Language

This is where an experienced workers’ compensation attorney becomes invaluable. Their job isn’t just to negotiate a big number; they are the architects of the agreement’s language. A skilled attorney understands the nuances of tax law and ensures the final document is structured to maximize your non-taxable funds.

They will meticulously draft the agreement to:

- Clearly state the settlement is for a personal physical injury.

- Itemize funds, separating medical costs from wage replacement.

- Avoid ambiguous terms that could imply taxable income, like punitive damages.

This level of detail is fundamental to securing your financial future. When considering legal help, understanding how to choose the right attorney for your case is a critical first step. The right professional will not only fight for a fair settlement but will also protect it from taxation through careful, deliberate wording.

Ultimately, the language in that final document will determine whether your settlement provides the financial relief it was truly intended for.

Your Post-Settlement Tax and Reporting Plan

Getting that settlement check is a huge relief, but it’s not quite the end of the story. Now, the focus shifts to managing those funds and squaring away any tax loose ends. A smart post-settlement plan is your best defense for protecting your financial future and staying on the right side of the IRS.

The good news? The lion’s share of your settlement—the money for medical bills and lost wages tied to a physical injury—is completely off the IRS’s radar. This isn’t considered income, so you won’t get a W-2 or 1099 for it, and you don’t need to mention it on your tax return.

Navigating Tax Forms and Reporting

But if any part of your settlement is taxable, you need to be ready for the paperwork. The most common one you’ll run into is a Form 1099-INT.

You’ll get this form if your settlement piled up interest because of payment delays. It’s not optional; the payer has to report that interest to you and the IRS.

When a 1099-INT lands in your mailbox, here’s the drill:

- Report the Interest: You have to include that interest amount on your Form 1040. It’s taxable income.

- Pay the Taxes: The interest is taxed at your regular income tax rate, just like the interest you’d earn from a bank savings account.

Ignoring a 1099 is one of the easiest ways to get a letter from the IRS. They already have their copy, so when your return doesn’t match their records, their system automatically flags it.

Can You Deduct Attorney Fees?

This question comes up all the time: can you write off the attorney fees that came out of your settlement? For almost everyone, the answer is a hard no.

The IRS logic is simple. You can’t deduct legal fees you paid to get tax-free money. Since the core of your workers’ comp settlement is non-taxable, the legal costs to win it aren’t deductible. This rule prevents what the IRS sees as “double-dipping”—getting tax-free cash and a tax deduction for the cost of getting it.

Think of it this way: The cost of producing tax-free income is not a tax-deductible expense. The legal fees are just seen as part of the cost of acquiring your non-taxable settlement.

Considering a Structured Settlement

For very large settlements, you might be offered a structured settlement. Instead of one big check, you get guaranteed payments over several years, or even for the rest of your life. This can be a great way to create a stable, reliable income stream.

One of the biggest perks is that the tax-free status of your original award carries over. Every payment you receive from the physical injury portion remains non-taxable. Just be aware that if the payment structure includes any kind of interest or growth factor, that specific portion might be taxable.

The Most Important Step You Can Take

Look, the financial aftermath of a settlement can get complicated fast. The single most valuable thing you can do is sit down with a qualified tax professional or a CPA. They can dig into your specific settlement agreement, clearly explain any tax hit you might face, and help you build a solid plan. It’s a small investment that buys incredible peace of mind and makes sure your settlement does what it was meant to do: secure your financial well-being for the long haul.

Common Questions About Workers’ Comp & Taxes

Even after you understand the fundamentals, real-world situations always bring up more specific questions. Let’s break down some of the most common tax concerns injured workers face.

Do I Have to Report My Settlement on My Tax Return?

For the vast majority of people, the answer is a simple no. If your entire settlement was paid to compensate you for a physical injury or illness, it’s not considered income. You won’t get a W-2 or 1099 from the insurance carrier for these funds, and you don’t need to report them on your tax return.

The exception to this rule is when a specific tax form arrives in your mailbox. If you receive a Form 1099-INT for interest payments or a 1099-MISC for another taxable component, you absolutely must report that income. A 1099 is the payer’s way of telling the IRS they paid you, so ignoring it is a surefire way to trigger an automatic notice from the government.

What if My Settlement Includes Money for Emotional Distress?

This is where tax law gets particularly tricky. The IRS has a clear rule: compensation for emotional distress is tax-free only if it originates directly from a physical injury or physical sickness. For example, if you developed PTSD after a traumatic fall on a construction site, the portion of your settlement for that emotional suffering would likely be non-taxable.

However, if your claim was for emotional distress without an underlying physical injury, that part of your settlement is almost always considered taxable income. The specific language in your settlement agreement becomes critical here, as it must clearly establish the link between the physical harm and the emotional toll to protect those funds from taxation.

The critical distinction is the source of the distress. If it’s a direct consequence of physical harm, it’s typically non-taxable. If it’s a standalone claim, the IRS will usually tax it as income.

Are Attorney Fees from My Settlement Tax Deductible?

In most cases, no. You cannot deduct attorney fees that were spent to secure tax-free income. Since the core of your workers’ comp settlement isn’t taxed, the legal costs you paid to get it are not deductible.

There is a narrow exception. If a portion of your settlement is taxable—like punitive damages or interest—you may be able to deduct the percentage of your legal fees that apply only to securing that specific taxable amount. This requires a complex calculation and is something you should only attempt with professional guidance from a tax advisor.

Protecting your settlement and financial future requires the right legal guidance. The Haute Lawyer Network is your connection to premier attorneys recognized as leaders in their fields, ensuring you receive the sophisticated advice your case deserves. Visit the Haute Lawyer Network to find an expert who can navigate the complexities of your claim.