Philippe Vergne is immediately recognizable as he bounces into The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles’ Selections from the Permanent Collection exhibition. With his slightly rumpled blazer, thick-framed glasses, black sneakers and floppy reddish-gold locks that would have looked right at home on a young Hugh Grant, Vergne seems more like a boyish art student than the buzz-worthy new director of MOCA. But make no mistake: his youthful appearance masks a wealth of experience. Vergne is the man who will restore the modern art institution to its former glory.

MOCA had embarked on a six-month, worldwide search after former director Jeffrey Deitch ended his tenure prematurely last July, resigning just three years into his five-year contract with the museum. Vergne, a veteran curator born in Troyes, France, was not on the market for a new job when the powers-that-be, a 14-person “search committee” comprised of Joel Wachs, president of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, board chairs emeriti Maria Bell and David Johnson, board president Fred Sands, board vice-chairs Eugenio Lopez, Lillian Lovelace and Maria Seferian, board co-chair Maurice Marciano, board president emeritus Jeffrey Soros, life trustee Blake Byrne, and artists John Baldessari, Barbara Kruger, Catherine Opie and Ed Ruscha, came a-calling.

Vergne had been happily running New York’s Dia Art Foundation when he received the very unexpected call from MOCA. “I wasn’t necessarily looking for anything, but the museum is a legend—it has the best collection of post-war art in the country—so when I picked up the phone, I became intrigued,” the 48 year old recalls in an accent dripping with Champagne-honeyed French from his office above the museum’s headquarters in downtown Los Angeles. “I also knew that the leadership of the institution had been extremely active and extremely supportive and was eager to foster change, so I told them that I would talk.”

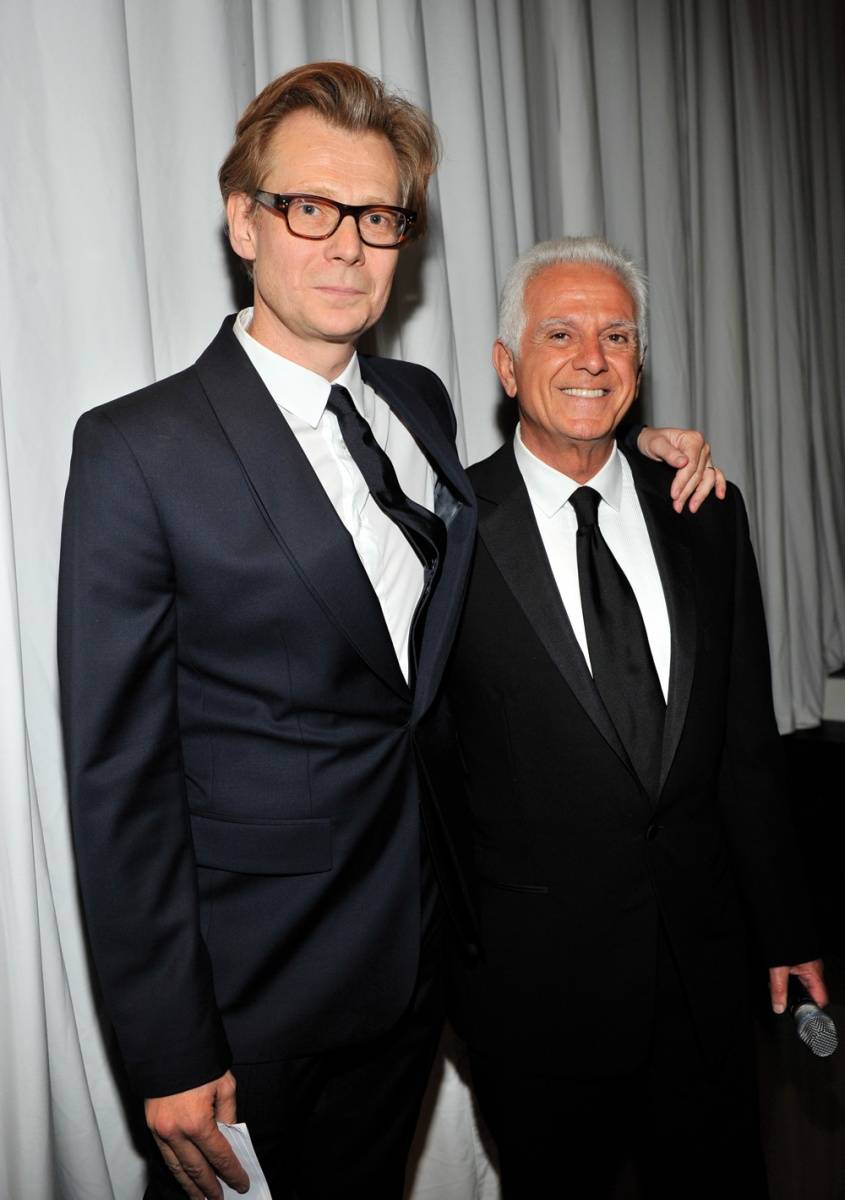

Cramer and an anonymous donor

Vergne didn’t realize how badly he wanted the job during the initial interview stages, but that changed rapidly. “When you start interviewing, at the beginning you don’t know that you want it, and then you really want it, and when someone says, ‘We’re making an offer to you,’ then you know immediately. You know it when you see it and when you hear it,” he says.

What Vergne wanted was the ability to make a significant change, which is exactly what he’s getting. “When you understand how much of a responsibility it is to take the institution to the next phase, and the challenge and excitement that comes with this responsibility, for me it was overwhelming,” he admits.

Though he jocularly declares that he was the right man for the job because he speaks “really good English,” all joking aside, Vergne is positive that his past experiences have more than prepared him for this current position of importance. He was the director of the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Marseille from 1994 to 1997 and a senior curator at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. He then returned to France to run the private François Pinault Foundation for contemporary art, before making his way back to Walker as its deputy director and chief curator in 2005. In 2006 he co-curated the Whitney Biennial before heading to Dia, an institution known for its ability to take risks, in 2008.

Though his most important career moves occurred in America, Vergne is still respectful of the experiences he had in his native country. “My professional life in France was very short – they kicked me out right away,” he jests, adding more seriously, “It prepared me because when I was younger, I was part of the creation of a new museum in the south of France. I was 27 years old at the time, and I had to learn a lot extremely quickly. It was a complicated situation, but it was there that I was privileged enough to meet with Pontus Hulten, a Swedish thinker, curator and museum director [who was also MOCA’s first director]. I met him towards the end of his life, and he became a role model for me.”

Even in France, Vergne says, it was always Los Angeles that had an impact on him. “My experience in France was so informed by the fact that I was looking a lot at what was happening in Los Angeles. I thought the artists working there, from Mike Kelley to Chris Burden to Barbara Smith, were so impactful.” He adds, “LA has been a center for art and creativity across the disciplines since the 1950s.”

He is also quick to credit Dia with giving him the skills necessary to tackle his current position. “When you’re the director of Dia, you have to be flexible and you have to learn to work with an institution which is very peculiar, so it’s a very good training ground and a very good platform to learn how to deal with the administration of an institution and the way an institution deals with artists.”

Coincidentally, he replaced Michael Govan at Dia, who left the institution in 2008 to become the director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. For the record, he doesn’t think that working at Dia is a natural precursor to working in the Los Angeles art world. “I think it’s serendipity that Michael and I ended up in the same city. We are both passionate about art and artists, and L.A. is a magnet for art and artists. Not that New York isn’t, but L.A. is definitely [a magnet], and I think we’re both adventurous people,” he declares.

Vergne also has high praise for his predecessor, Jeffrey Deitch, whose tenure at the museum has been described at best as adventurous, and more frequently with adjectives like stormy, tumultuous and rocky. During his three years working with MOCA, fundraising substantially dropped and four prominent artists, including John Baldessari, Barbara Kruger, Catherine Opie and Ed Ruscha, among others, resigned from its board.

Though it has been said that the museum desperately needed to retain its integrity as “The Artist’s Museum,” Vergne, for one, is adamant that the museum has always remained true to that sentiment, and defends Deitch’s direction.

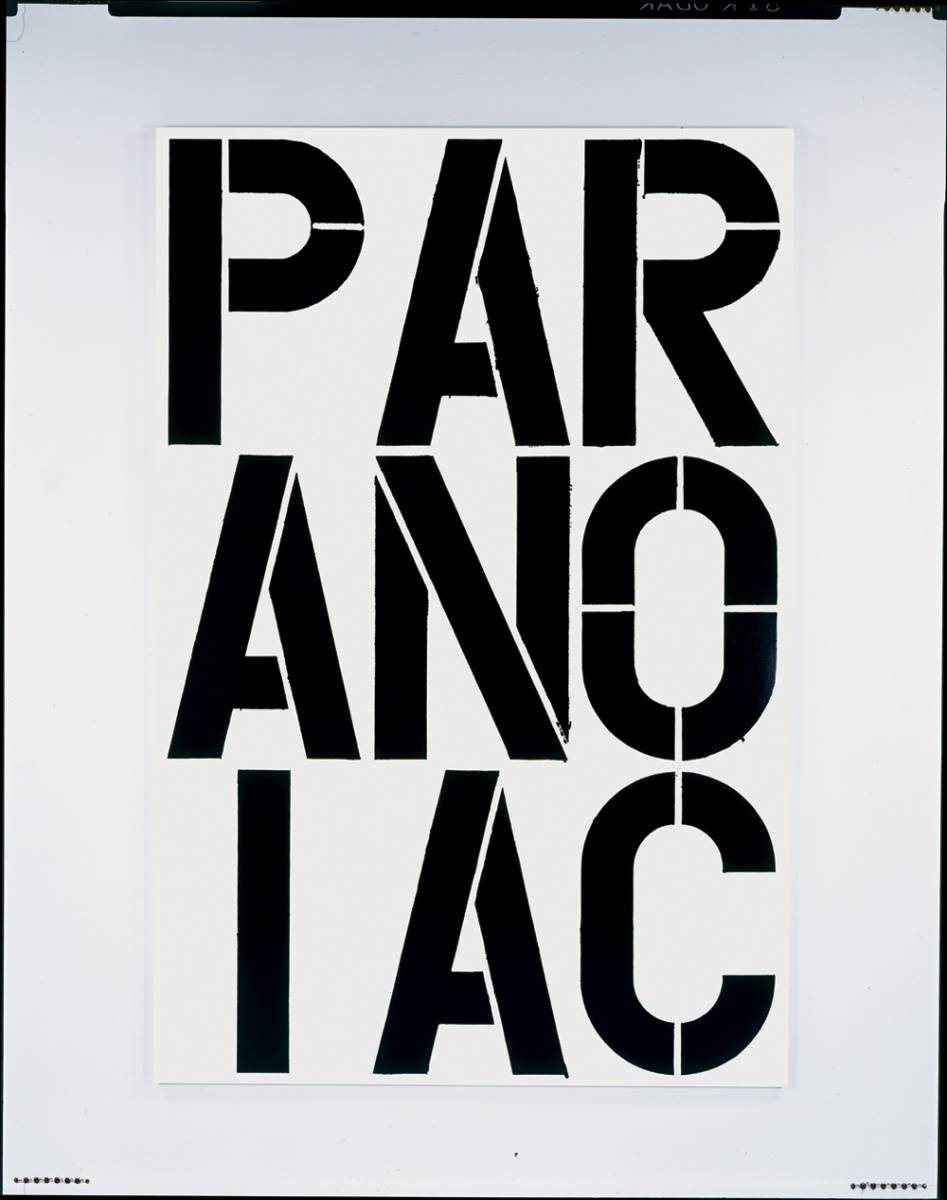

“MOCA never left the idea of the artist’s museum; it’s in it’s DNA,” he maintains. “[Naysayers are] entitled to their opinion. Things happen; people agree and disagree, but the institution is bigger than the individuals. I think that people understand the idea of the artist’s museum differently, and that there is not just one way of implementing that idea. I think bringing a group of artists to the program that have never been represented in an American museum because of the nature of their work, their aesthetic, contributes to making this an artist’s institution. I’m talking about street art,” he says, referring to the 2011 Deitch-implemented “Art in the Streets” exhibit of graffiti and street art. He adds, “Whether or not they were part of an institutional tradition, we can talk about that. But if this exhibition ticked people off and [made them say that MOCA] was no longer an artist’s institution, then I think they’re wrong.”

There is something so earnest and genuine about Vergne, whether it is in his defense of he museum’s past decisions or in his discussion of the very positive relationships he has with the MOCA board, that it’s no wonder his reception in L.A. has been so well received. Three of the four artists who left during Deitch’s term have returned. The fourth, Ed Ruscha, has opted out, though Vergne is confident it is a timing issue, nothing more and nothing less.

“We asked Ed, and he was extremely supportive [of the museum], but has made a different commitment. He was on the board for a very long time. I don’t think his decision not to rejoin the board is related to who we are; it’s related to his time commitment and availability.” Abstract painter Mark Grotjahn has since filled the place Ruscha vacated, and Vergne, for one, couldn’t be happier. “Change is good!” he notes.

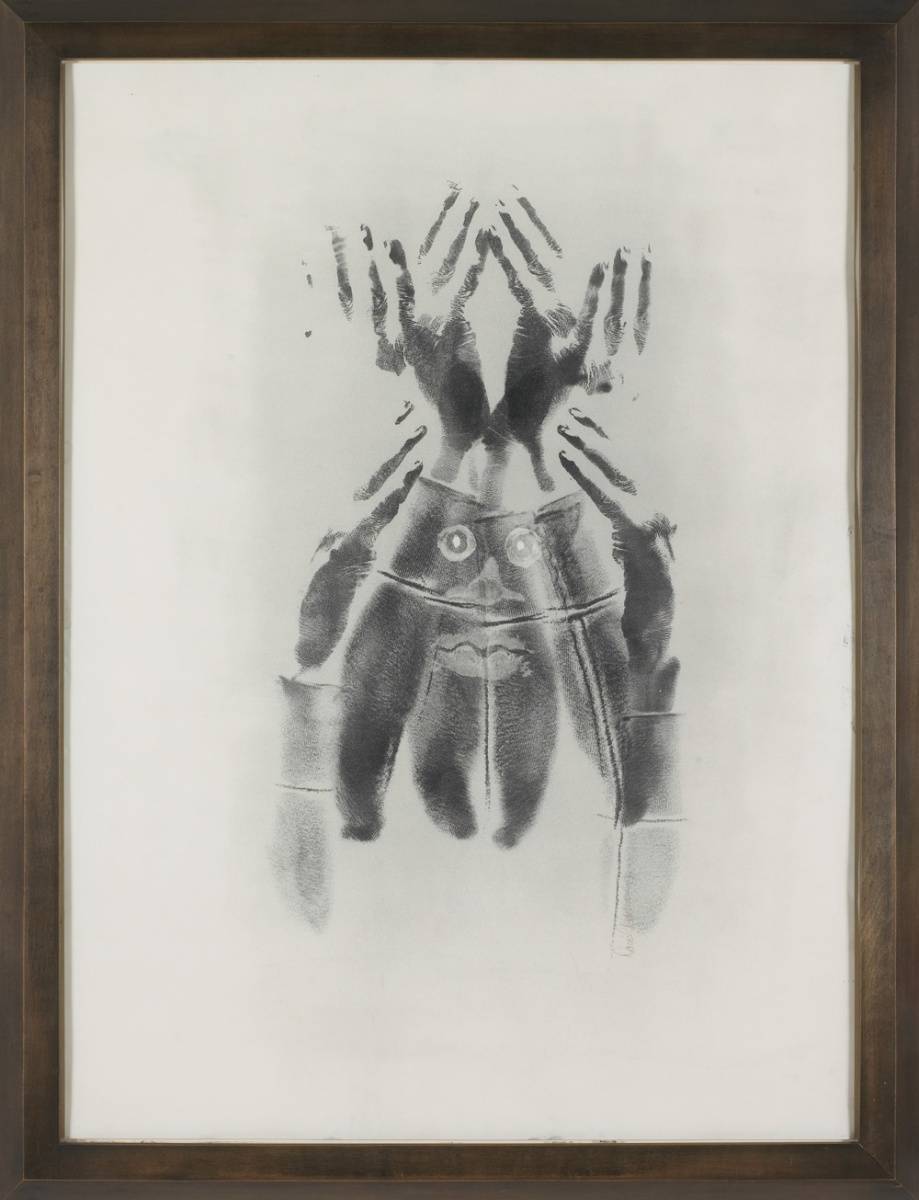

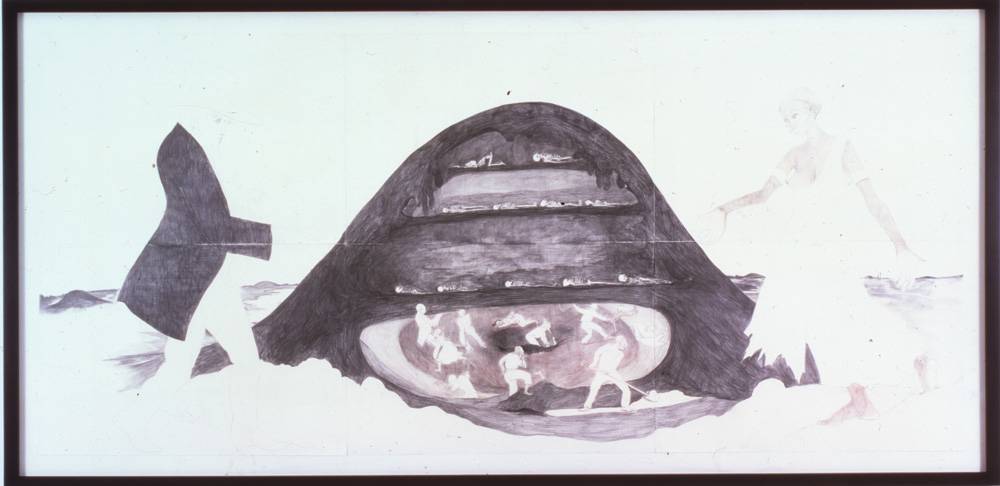

While he’s all for it, Vergne knows change won’t happen overnight. “You don’t change an institution in one day. It takes time, even when you move quickly,” he notes. “What we need to be aware of at both the staff and board levels is that even though there is an urgency to act quickly, an institution needs time to change. The long range plan is to continue to bring innovative artists in all the time, to continue to be artist-centered, to continue to promote artists to take risks and further their visions across disciplines, across cultures and across generations. It’s really making sure that we can bring our audience to the edge of what they know and understand. What makes art today, and what is the most innovative art today – that’s the center of this institution.”

He will continue to strive to increase MOCA’s endowment fund, which recently not only reached its goal of $100 million, but has increased said goal to $200 million. He will continue to cultivate new museum patrons, will work on creating innovative new exhibitions like the recent Mike Kelley and Cinema Vezzoli exhibits, and will continue to partner with brands like Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Fendi to bring new luxe life to the institution.

He will also work alongside Eli Broad’s soon-to-be-opened Broad Art Museum by creating a synchronicity that will benefit both downtown art institutions. “There is a lot of unknown right now, but the first step in the conversation is to acknowledge that there are a lot of unknowns,” Vergne says. “I’m convinced that having the Broad Museum here across the street will help us, and I’m also convinced that having us across the street from them will help them. I think Eli’s collection is very different from our collection – different but fantastic. We will grow complementary to each other.”

Though he has a lot to tackle in the upcoming months, his biggest challenge is actually finding time to explore the City of Angels. Though he has been coming to LA for 20 years, he hasn’t had much time for exploration beyond the walls of MOCA and his own Hancock Park home. Still, he says, “I feel totally immersed in the city because I’m breathing it,” citing Topanga Canyon, the Geffen Contemporary, Venice’s Abbot Kinney and the Museum of Jurassic Technology among his favorite locales.

Another adjustment, of course, is getting used to being amongst the glitterati of Hollywood. At MOCA’s 35th annual gala on March 29, which also served as his welcoming party, Vergne was surrounded by the likes of Katy Perry, Jane Fonda, Dita Von Teese and Ryan Seacrest, among others.

Though he is unused to being surrounded by the fame and fortune of the Los Angeles art-loving community, MOCA’s director is well up for the task. “I think Hollywood is an art world of its own. It’s fascinating to me, and I need to learn from it.” He then adds of the gala, “I thought I was in a movie.”

Welcome to your new life, Mr. Vergne.