Flying thirty thousand feet above the barren hills of Haiti, I took my time filling out the immigration form. I stopped at the section entitled “Reason for travel.” My options were as follows: A) Business, or B) Pleasure.

I stopped and wondered why I had come. I was not sure what had brought me to this place and yet I was meant to check myself into one of these two little boxes. I put the pencil down. If only life were that simple.

Founded by two Haitian natives, Michael Pradieu and Unik Ernest in 2007, the school clothes, feeds, and educates over three hundred boys and girls from this earthquake ravaged slum.

I did not know yet why I had come to Haiti, all I knew was that a door had opened, and I had walked through it. I had passed many open doors in my life and by the time Nora Gherbi informed me she was going to Haiti to check on the kids at the Edeyo School in Port-au-Prince, (this, over coffee and poached eggs just seven days prior at an east side French bistro) I knew I had to go. “I’m coming with you.” It wasn’t a request.

“You should.” She shrugged slightly. Nora, a French diplomat and board member of the not-for-profit school Edeyo, extended the invitation further. “You can take pictures of the kids. I’ll send you my itinerary.”

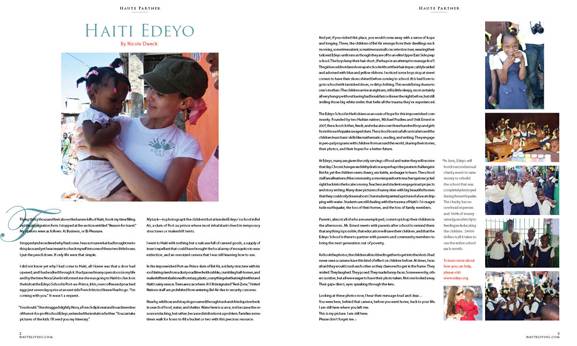

My task—to photograph the children that attended Edeyo’s school in Bel Air, a slum of Port au prince where most inhabitants lived in temporary structures or makeshift tents.

I went to Haiti with nothing but a suitcase full of canned goods, a supply of insect repellant that could have brought the local army of mosquitos to near extinction, and an oversized camera that I was still learning how to use.

In the impoverished Port-au-Prince slum of Bel Air, a rickety structure with tin roof slating rises from a dusty road lined with rubble, crumbling half-homes, and makeshift tents fashioned from tarp, plastic, or anything else that might withstand Haiti’s rainy season. Trees are scarce here. A U.N designated “Red-Zone,” United Nations staff are prohibited from entering Bel Air due to security concerns.

Nearby, wild boar and stray dogs roamed through trash and dried up riverbeds in search of food, water, and shelter. Water here is scarce, not because the resource is lacking, but rather, because distribution is a problem. Families sometimes walk for hours to fill a bucket or two with this precious resource.

And yet, if you visited this place, you would come away with a sense of hope and longing. There, the children of Bel Air emerge from their dwellings each morning, sometimes a tent, sometimes a small concrete structure, wearing their tailored Edeyo uniforms as though they are off to an elite Upper East Side prep school. The boys keep their hair short, (Perhaps in an attempt to manage lice?) The girls would not dare show up at school without their hair impeccably braided and adorned with blue and yellow ribbons. I noticed some boys stop at street corners to have their shoes shined before coming to school. (It is bad form to go to school with tarnished shoes, or dirty clothing. This would bring shame to one’s mother.) The children arrive at eight am, still a little sleepy, most certainly all very hungry without having had breakfast or dinner the night before, but still smiling those big white smiles that belie all the trauma they’ve experienced.

The Edeyo School in Haiti shines as an oasis of hope for this impoverished community. Founded by two Haitian natives, Michael Pradieu and Unik Ernest in 2007, the school clothes, feeds, and educates over three hundred boys and girls from this earthquake ravaged slum. The school boasts a full curriculum and the children learn basic skills like mathematics, reading, and writing. They engage in pen-pal programs with children from around the world, sharing their stories, their photos, and their hopes for a better future.

At Edeyo, many are given the only servings of food and water they will receive that day. Chronic hunger and dehydration are perhaps the greatest challenge in Bel Air, yet the children seem cheery, excitable, and eager to learn. The school staff are all natives of the community, so monies paid out to teachers gets recycled right back into the local economy. Teachers and students engage in art projects and story writing. Many draw pictures of sunny skies with big beautiful homes that they could only dream about. One student painted a picture of a faucet dripping with water. Students are still dealing with the trauma of Haiti’s 7.0-magnitude earthquake, the loss of their homes, and the loss of family members.

Parents, almost all of who are unemployed, come to pick up their children in the afternoons. Mr. Ernest meets with parents after school to remind them that anything is possible, that education will save their children, and that the Edeyo School is there to partner with parents and community members to bring the next generation out of poverty.

As I took the photos, the children all mobbed together to get into the shots. I had never seen a camera have this kind of effect on children before. At times, I was afraid they would crush each other as they clamored to get in the frame. They smiled. They laughed. They posed. They made funny-faces. Some were shy, others somber, but all were eager to have their photo taken. Not one looked away. Their gaze direct, eyes speaking through the lens.

Looking at these photos now, I hear their message loud and clear…

You were here, behind that camera, before you went home, back to your life.

I am still here where you left me.

This is my picture. I am still here.

Please don’t forget me.

In June, Edeyo will host its second annual charity event to raise money to rebuild the school that was completely destroyed during the earthquake. The charity has no overhead expenses and 100% of money raised goes directly to feeding and educating the children. $4,000 dollars is all it takes to run the entire school each month.

To learn more about how you can help, please visit www.edeyo.org